On background: I mounted my first reporting trip to the Balkans in March 1992 from my base in Prague, Czechoslovakia, where I had been covering the aftermath of the recently ended Cold War. Months of brutal civil war to the south in Croatia was wrapping up with a peace agreement, to be initially enforced Canadian troops under the United Nations banner. Opportunity was knocking. The Canadian Press had agreed to look at my proposed deployment stories on “spec,” meaning no guarantees they’d buy them. My first taste of significant ground combat occurred in the virtually flattened northern Croatian frontline town of Pakrac (pronounced Pack-ratz), where the Canadians were supposed to deploy. I saw lots of front-line fighting in that town and sold my first two Balkans war stories to the Canadian Press for $300, the start of a long-term stringing relationship. Before I departed to Prague, the siege of Sarajevo and Bosnia war broke out. I was hooked. A few months later, I packed my bags in Prague and moved to Zagreb, the capital of Croatia to cover all of the conflicts. What follows is a relatively select representative sampling of stories I reported until I returned to the U.S. in August 1993.

The war in Bosnia featured three main parties: the Catholic Croats, the Orthodox Christian Serbs and the Muslims. For much of the war, the Croats and Muslims allied against the Serbs, effectively, though no love was lost between them. Then, suddenly, in the summer of 1993, they turned against one another. I was in the midst of traveling in central Bosnia when the fighting broke out and found myself trapped for nearly five days in the village of Jablanica, the road in and out blocked by one side or the other. I reported as best I could from Jablanica and, with the help of local Spanish troops, faxed my story out. Here is that story:

Former allies in Bosnia at each other’s throats

By Todd Bensman

Times Correspondent

The St. Petersburg Times

April 16, 1993

JABLANCIA, Bosnia-Herzegovina – For weeks, the 2,000 people who live in this sleepy, predominantly Muslim village were expecting a showdown. It came with a bang about noon Thursday.

Bosnian Croats in the steep, wooded hills above town started shelling the Muslims here, their erstwhile borthers-in-arms against the republic’s Serbs. Jablanica is far enough away from Serb guns to have escaped the horrors of the yearlong Bosnian civil war.

Now the town, a conduit for overland humanitarian aid to eastern enclaves surrounded by Serbs, is cut off from the outside world as the long-simmering power struggle between Muslims and Croats fractures what is left of the country.

“Everything is very tense,” said Maj. Nestor Suarez, commander of the Spanish contingent of the United Nations forces here. “Everyone is very nervous.”

An exchange of gunfire set off a fuse shortened by months of tension between Bosnian Croats apparently trying to cement control over this region as part of a self-proclaimed “Republic of Bosna-Herzog,” and the Muslims who oppose them. Resounding from the eastern part of Jablanica, the gunfire caused pandemonium in the streets. Residents sprinted in all directions to seek shelter as cars squealed in reverse out of parking lots.

Then the first mortar shell landed in the town proper, causing more panic. As air-raid sirens wailed, and the streets filled with frenzied people and confused soldiers running for the protection of basement bomb shelters. Within minutes, the streets were empty except for a few vehicles screeching at high speed around abandoned corners. Shellfire boomed through town, the succession of explosions followed by loud echoes off the jagged mountains surrounding Jablanica.

There was no word on injuries.

At the command headquarters of the Bosnian army, confusion reigned.

None of the commanders or soldiers crammed inside could say what was happening. In the on-and-off warfare between Croats and Muslims in the last few months, there are no clear front lines. The soldiers milled around the headquarters waiting for orders, listening impotently to explosions while cursing Croats. Terrified women and children cried.

“They are not Croats; they are animals,” said one of about 25 civilians who took refuge in the headquarters basement.

U.N. officials say this round of the conflict is much more serious than past eruptions. Altogether, the fighting involves more than 20 rural towns and villages in a district dominated by Muslims, according to the U.N. and local commanders.

To many Muslims here, relations with the Croats are permanently soured.

“After this, I don’t think we can ever fight together again,” said one soldier. “I cannot trust any Croatian soldier fighting next to me. I could never be sure he would not kill me behind my back.”

The events leading to this latest violence began about a week ago. The better-armed Croat forces reportedly attempted to extend their political and economic control over local governments in villages where Muslims predominate. The region has a hydroelectric power station that feeds southern Croatia, an arms factory and a strategic bridge over the Neretva River.

Thursday was the deadline for al soldiers who do not live in the area to hand over their weapons to Croat command.

When Bosnian soldiers resisted in Jablanica, Croat forces pulled out of town. On Wednesday, they attacked dozens of area villages with heavy artillery, tank fire, mortars, and anti-aircraft machine guns. New checkpoints sprunt up so quickly that travelers and aid convoys found themselves trapped in Jablanica. Asked what his orders were, a Croat soldier manning a heavy machine gun on an armored personnel carrier answered only: “total blockade.”

Meanwhile, the attacks Wednesday targeted the tiny village of Ostrazac, five miles from Jablanica. About 120 refugees in an abandoned school building huddled in bathrooms and on a basketball court deemed safe enough to withstand a hit.

“Fifty of us were crammed into the toilet all day long,” said Joza Mula, a 68-year-oldMuslim refugee from another town. “I thought this was a safe place, but now the Croats are going the way of the Serbs because they are shelling us the same way.”

On Background: This next story about a terrible atrocity in the central Bosnia town of Ahmicic, in April 1993, is remarkable in two ways. Croat militiamen slaughtered and burned 97 Muslim residents in their own houses the day before we arrived in the area and decided to go in. We were among the first reporters to arrive after the massacre, although British troops had removed some bodies and departed. But the British had missed some of the living. We discovered that a Croat family had risked hiding the last Muslim family in their basement, saving their lives at serious risk to their own, and that these Muslims were still in the basement. Second, my two Italian journalist colleagues and I arranged for their rescue. We secured a vehicle for them, helped them out of the basement to it with only what they could carry, then escorted them through sniper fire to a British U.N. base. Years later, the International War Crimes Tribunal convicted Croat leaders for crimes against humanity for what we saw in that town.

Unlikely ally saves Muslims from ‘ethnic cleansing’ 97 slain in one village

AHMICI, Bosnia-Herzegovina – Avoiding the sight of their charred home, the Ramic family wiped away their tears of gratitude, hurriedly boarded a Land Rover and became the last Muslim family to leave this village alive.

Their plight began after vicious fighting broke out April 15 between Bosnian Croat and Muslim forces in central Bosnia. Croatian militia went from house

to house in the region – shooting, burning to death and capturing Muslims in a savage campaign of “ethnic cleansing.” More than 200 people are thought to have been killed in the area surrounding the Croat-held city of Vitez, including one Muslim family of seven found burned to death in Ahmici.

But for Ramo Ramic, his wife, Dervisa, and Dervisa’s 86-year-old mother, Ema Ahmic, salvation came from an unexpected quarter. Their Croatian neighbors, at great risk to themselves, hid the Ramics in a shuttered back bedroom for seven terrifying days while the ethnic cleansing was carried out.

“If they hadn’t existed, we would be dead now,” said Dervisa Ramic, 38, a bookkeeper. “The best thing is that we were not alone. We were with friends.” After the fighting died down, the family’s Croatian benefactors – a man, his wife and their two sons – exchanged long, tearful hugs with the Ramics as they prepared to leave. “They were my neighbors. They were always my friends,” said the Croatian man, struggling to speak through sobs. “When I heard trouble coming I went over to their house and brought them over. I couldn’t let them die.”

Before the violence broke out, armed strangers came to town and warned Croat residents that extremist Islamic fighters from Iran were marching on Vitez. The same soldiers had a different message for Muslim residents – leave or be killed, according to the Ramics.

Then the shooting began. A day later it had turned into a maelstrom of mortar, artillery and firefights. During the battle, Croat militia rampaged through the village burning, looting and killing Muslims who had not already fled.

The Croatian neighbors found the Ramic family huddled in their basement next door and brought them home. A few hours later, the Ramic house was in flames.

“The house was completely full of all our possessions. We lost everything,” said Ramo Ramic, a 44-year-old homebuilder. “What happened in Ahmici is the highest tragedy. It is the worst thing that could have happened.”

The village, which was about 40 percent Croatian, is a burnt remnant of its former self. Almost every other house is a blackened wreck.

The corner grocery store flies a large Croatian national flag on its outer wall. Smaller versions of the same banner hang from power lines, defiantly proclaiming this town Croatian territory.

Throughout their ordeal, the Ramics said they could trust no one – not even their other Croatian neighbors, who they feared might inform paramilitary units prowling Ahmichi’s prim dirt streets and multilevel brick houses.

For seven days, they dared not stray from their room, fearing even to speak too loudly. The Croatians brought them food. Windows were shuttered.

A mere knock at the front door was enough to bring terror to the house. Soldiers came to the door several times asking if the Croatian man knew of the whereabouts of Muslims. But he said he lied each time, and they believed him.

“I was afraid of the soldiers. It could happen that one of the soldiers who is crazy would see us,” said Dervisa Ramic’s mother, Ema. “I was so afraid they would kill us, but thank God they never did.”

The cleansing of Ahinici was long over by the time the family dared to creep from their hiding place to make a getaway to the Muslim-controlled town of Zenica, about 25 miles away, where their 18-year-old son had been staying with cousins.

British and Dutch U.N. protection forces in Vitez refuse to get involved in the conflict because of fears they will be accused of taking sides. So when he judged it safe enough, the Croatian neighbor arranged the Ramics’ evacuation with a sympathetic Croatian doctor from Vitez who owns the Land Rover.

The doctor, who did not wish to be identified, told the family he could not guarantee they could escape from Vitez without U.N. help. As a Croatian, he could not risk crossing Bosnian army roadblocks on the way to Zenica, he said.

Driving slowly down the hill and out of Ahmichi toward a Dutch U.N. base, the vehicle was exposed to sniper fire. The Land Rover stopped at the base, where the doctor got out to plead his case. But the sergeant at the gate refused to accept responsibility for the refugees. Then sniper fire broke out again, and the vehicle sped around to a safer side of the compound.

“We can’t choose one side or another,” Sgt. Bart Navis explained. “If we take them, they shoot at us too and we don’t have weapons to defend ourselves.”

But an officer promised to call the British up the road. A few moments later, several British soldiers in jeeps pulled up and agreed to carry the Ramics into Zenica once a shootout up the road had subsided. Two hours later, the Ramics were deposited on the side of the highway in Zenica.

They were last seen boarding a local police van that would take them to the home of their relatives, where they will begin a new life as war refugees.

The Canadians

On background: I spent much time covering Canadian soldiery all over the Balkans. Canadians were the first U.N. Peacekeepers deployed to the war zone in the spring of 1992, to Daruvar, Croatia. I was there to greet them and report about them. But later, armored divisions of Canadian soldiers were redeployed into red-hot Bosnia. My relationship with the Canadian Press news service dictated that I continue to cover them, and I did. Following is a selection of a great many stories I did about the Canadian military experience in the Balkans.

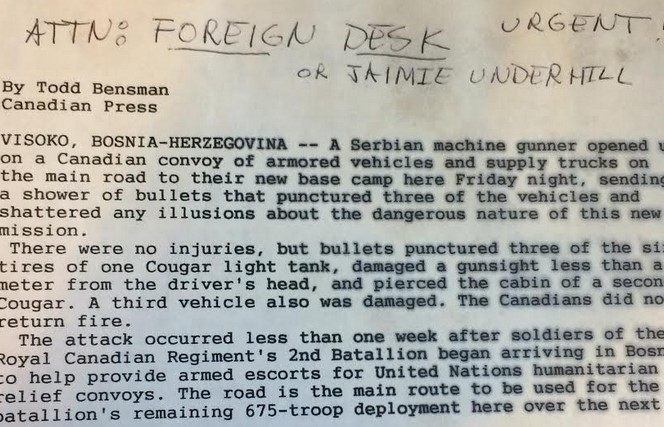

Canadian soldiers attacked in new Bosnia post

No return fire raises U.N rules of engagement issue

Todd Bensman

Canadian Press

Date unknown (1993)

VISOKO, Bosnia-Herzegovina – A Serbian machine gunner opened up on a Canadian convoy of armored vehicles and supply trucks on the main road to their new base camp here Friday night, sending a shower of bullets that punctured three of the vehicles and shattered any illusions about the dangerous nature of this new mission.

There were no injuries but bullets punctured three of the six tires of one Cougar light tank, damaged a gunsight less than a meter from the driver’s head, and pierced the cabin of a second Cougar. A third vehicle also was damaged. The Canadians did not return fire.

The attack occurred less than one week after soldiers of the Royal Canadian Regiment’s 2nd Batallion began arriving in Bosnia to help provide armed escorts for United Nations humanitarian relief convoys. The road is the main route to be used for the battallion’s remaining 675-troop deployment here over the next week.

The vehicles were deliberately targeted,” said Lt. Col. Tom Gebert, the batallion’s commander. “We were engaged.”

Three long bursts from the machine gun came just after dark as 10 behicles of the regiment, on their way from Kiseljak, rounded a bend in the one road to the Visoko known to be exposed to sniper fire from a machine gun nest just 200 meters away. Earlier in the day, a civilian truck came under attack at the same bend.

Cpl. Eric Jacques of Montreal was a passenger in a 1 ¼-ton mobile repair vehicle that was between the two Cougars and took a bullet throught he front grill. As he made repairs on the vehicle Saturday morning, he told what happened.

“As soon as we hit that place, I saw on top of the mountain there the flash of a machine gun. I saw the tracers coming down at us. I got down under the dash. When I looked up, I saw them (the bullets) hit the Cougar (in front). There were green, red and blue flashes where they hit. It went thunk, thunk, thunk.

“At the same time we heard the bursts,” he continued. “It was real close. The Cougar stopped, and I got down under the dash again. Then he hit the gas, and we got out of there.

Cpl. Gilles Siros of Green River New Brunswick was driving. He said at first he thought the convoy had hit a firecracker booby trap laid by some local kids.

“I saw those flashes on the road, and then I said ‘that’s it.’ Give me my iron pot (helmet),” Siros said.

Less than a week into their presence in Bosnia, the Canadians already are confronted with the agonizing question of when and how to engage in combat. The rules of engagment under the U.N mandate for the six-month mission allows escort troops to return fire only in self defense.

But despite those rules, British, French and Spanish escort troops who have been under almost constant attack in Bosnia for the past three months have complained bitterly about political and diplomatic pressures that have forced them to exercise restraint even when faced with situations that clearly fall within the mandate.

What Friday’s attack seems to show is that for the time being Canadian forces too will have to suffer the frustration of being fired on with little encouragement from their commanders to shoot back. Pressure to lift those restraints grew so intense that the U.N. Security Council approved a resolution last week ostensibly granting ground troops more leeway to fight back. So far, there is no evidence to suggest the resolution has been used to expand the rules of engagement for the Canadians or anyone else.

Although the Canadians use the Visoko road day and night, Lt. Col. Gerber said in an interview Saturday he has instructed his troops to speed up and invoke caution rather than firepower unless the sniper’s position can be positively identified, a nearly impossible task for vehicles speeding past. There will be no attempt to take out the sniper’s nest, U.N. officials said.

“The rules of engagement are toally adequate. If we are engaged, and you can absolutely determine where the fire is coming from, we can fire back,” Gerber said. “We’ll just have to be cautious around that corner.”

Maj. Brett Boudreau, a Canaidan U.N. spokesman, said Friday’s attack was a sobering message to any of the arriving troops who had not yet graspred the stark realities of duty in Bosnia.

“It certainly brought it home a bit about where you are,” he said. “I think people are going to be more wary now. Now that our vehicles have taken hits, people will be more alert and vigilant.”

That goes double for Cpls Jaques and Siros.

“I’m gonna put my helmet on next time,” Siros said. “In fact, I carry it on my head all the time.”

Said Jaques, “Everyone was all right. That’s the point. Everybody made it back.”

Canadian soldiers called to investigate atrocities

Reports that Croat militias raped Muslim women, executed men and forced families to watch pushes U.N mandate rules

Todd Bensman

Canadian Press

Date unknown (1993)

KISELJAK, Bosnia-Herzegovina – A Canadian detachment of United Nations protection forces on Sunday were to investigate reports of atrocities allegedly committed in two villages near their base camp here during a week of fighting between Bosnian Croats and Muslims.

The operation, involving three armored personnel carriers, was an extension of a routine patrol but represents the first significant departure from the Canadian mandate to escort humanitarian relief convoys into besieged Bosnian enclaves elsewhere.

“We’re going in to see of the stories are true. If it is, then we’ll report,” said Capt. Steve Whelan of Gagetown, New Brunswick, who is in charge of patrols in the region. “We have orders to go look.”

Whelan said in an interview Saturday night that commanders of the Bosnian army have complained to Canadian forces in the area that members of the Croatian Defense Forces (HVO) have raped Muslim women, taken prisoners and executed military aged men while forcing their families to watch. Similar reports to British U.N. forces based in Vitez, 50 miles west of Kiseljak, have proven true, and resulted in a dramatic expansion of their operations.

The British Royal Cheshires Regiment over the last week, shocked after finding women and children burned to death in Ahmici, have been checking all reports of atrocities, helping to transport refugees out of the area and carting off corpses and people wounded in the fighting. While British commanders say they choose to construe such activities as within the U.N. mandate, Canadian commanders have until now said they would interpret the mission more rigidly.

“What we are doing now is far beyond the mandate, but we consider what we are doing as humanitarian aid,” said Maj. Martin Waters, spokesman for the Cheshires.

Canadian spokesmen could not be reached Sunday to discuss the operation. But earlier in the week, they ruled out becoming involved in the conflict broiling around them other than to monitor it.

“It’s not in our mandate,” said Capt. Marcel McNicoll, a spokesman for the Canadians. “We are not police.”

Fighting between Croats and Muslims, who have been allied against the Bosnian Serbs for more than a year, erupted throughout central Bosnia about 10 days ago. U.N. officials and other observers say the two sides are feuding over control of territory, and that the extremist elements from outside the country are fueling the conflict. Both sides are burning houses and “ethnically cleansing” areas they control.

The 270 Canadias from two combat companies who are based in Kiseljak have witnessed the battle in the area day after day from an old brick factory on high ground. Despite intense fighting throughout the Kiseljak area, the Canadians have continued their routine patrols, designed to instill a sense of security in the local population. Until now, however, the patrols have scrupulously avoided becoming involved in the latest conflict.

“We patrol just to say we’re here, but otherwise our hands are tied,” said Capt. Jerry Collier, a British exchange officer in command of the base.

There are similarities between the Vitez and Kiseljak regions. Both have major population centers surrounded by isolated villages that are being systematically burned and where atrocities may not be immediately discovered.

In the Vitez area, many of the confirmed atrocities were committed in tiny outlying villages during heavy fighting. British forces are uncovering new corpses from the rubble every day.

It remains uncertain whether Canadians here could be ordered to undertake extracurricular duties similar to those of the British if Sunday’s patrol of the two villages reveals atrocities had been committed.

Canadian mail carrier braves combat conditions

Todd Bensman

March 5, 1993

Canadian Press

KISELJAK, Bosnia-Herzegovina – Other mail carriers worry about vicious dogs, irate residents and bad weather. Canadian army Warrant Officer Eppie Goumans has more pressing concerns.

Every day, this mailman suits up in a bulletproof vest, sings his C-7 automoatic rifle over one shoulder, a bag of mail over the other and crosses Serbian lines into besieged Sarajevo to make his deliveries. The 40-year-old from Trenton, Onterio is the only link to the outside world for hundreds of United Nations soldiers in Sarajevo and central Bosnia.

Weaving through sniper fire, artillery and mortar barrages in a five-ton U.N. Truck is a routine Goumans says is worth the pleasure the contents of his big blue mailbags brings other soldiers.

“We are professionals. We deliver no matter what. If it means we go every day, seven days a week, Christmas and New Years, then we go,” said Goumans, a balking man whose grey eyes have seen much in the past four months. “They always say there’s a bullet with your name on it. We’re not scared of that. We’re scared of the one that says ‘occupant.’” But, continues,

“Our job is just to deliver the mail no matter what.”

About the only thing that prevents Goumans and his colleagues from delivering the mail are the firefights between Serbian and Bosnian forces on the road from Kiseljak to Sarajevo. Along one particularly volatile stretch, the road itself is a front line between warring factions.

In December, Goumans had to give up his soft-skinned mail truck for an armored personnel carrier. Goumans arrived in the central Bosnian town of Kiseljak last October. It is the headquarters for a massive United Nations relief effort in this war-torn former Yugoslav republic.

Goumans, a grandfather and career army man with 20 years service, has eight more months to serve in Bosnia. He said the past four have changed him, but he woulnd’t talk about his experiences.

“That’s a very personal thing. There have been times hwen we’ve come back from Sarajevo that we’ve had to seek someone out to talk to. You can only talk to someone here who has been through it and understands.”

Asked if he worries, Goumans stared at the mailroom floor for a few moments, then looked up and said: “I never worry about things I have no control over.”

Goumans and his French, Belgian, Danish and British colleagues who deliver mail learned fast. After his first few runs, Goumans traded his standard army issue flak jacket for one with armored plates. With is live-fire military training and his grasp of the subtle details of life peculiar to war-worn Sarajevo, Goumans hopes to boost his odds of survival.

It is a strange thing for a mailman to think about, but “I look for birds,” he explained, “And if I see birds along the road, then I know it’s quiet. I look at the people. Are they outside? Are they running? Are they waling fast? If they are, I know there’s danger around.

“I have a philosophy: I do not go anywhere that I am not supposed to go. My job is to go from point A to B to deliver the mail.”

In his four months, Goumans hasn’t been fired at, nor has he had to fire his weapon. “I’ve never even had a dog bite,” he said.

Christmas for Canadian soldiers in Bosnia: blowing up a booby-trapped tree

Todd Bensman

Canadian Press

December 26, 1992

DARUVAR, Croatia – Canadian UN peacekeepers in Croatia spent much of Christmas Day blasting a Christmas tree into a million splinters. Someone during Christmas Eve – probably not Santa Claus – decorated the wreathed tree at a well-travelled road junction with a fragmentation mine. The culprits then wired the explosive to a re-election campaign poster of Croatian President Franjo Tudjman they had hung on the tree. Two more mines were tied to a pole flying the Croatian flag nearby.

Pte. Keith Reynolds of Winnipeg, out on patrol with several other members of Delta Company on Christmas morning, was admiring the tree when he noticed the interesting decoration on top was not the Star of Bethlehem.

“I said… look at that. I’ve never seen a Christmas tree like that.”

The area was taped off and members of the Canadian combat engineers regiment were called in. Later in the day, they demolished the mine – along with the tree.

So went Christmas in Croatia, where more than 2,000 Canadian peacekeepers spent the day like any other, attempting to calm ethnic hatreds that would turn a peaceful holiday symbol into a booby trap.

The Canadians, as usual, rattled down roads in their armored personnel carriers and stopped travelers to check for weapons. But at a few UN outposts, some off-duty soldiers washed down roasted pig and abundant pastries with glasses of “moose milk,” a rum-based drink.

Others waited in line for their turn to call home for 10 minutes. Some raucous parties were reported in the nights leading up to Christmas, lubricated with Labatt’s Blue beer, local liquor, and wine, and the ever-present moose milk.

More were planned Christmas night.

“It doesn’t seem like Christmas but we do our best,” said Cpl. Daniel Ross of Victoria, shruggin his shoulders and taking another chug of moose milk in a UN barracks near Pakrac. “The Canadian army is one of the world’s last “wet armies,” quipped Pte. Dwight Wiens of Calgary as he stood in line for his turn at the telephone. “They treat us like real men.”

Many of the locals celebrated the holidays by firing their weapons into the air all night Christmas Eve, adding a bit of adrenalin to the moose milk flowing through the bloodstreams of the soldiers.

“There was a hell of a lot of shooting. Man, tracers were going everywhere,” said Warrant Officer Kevin Crone of Winnipeg. “Just as long as they keep it aimed up at the sky and not horizontally.”

In the town of Torang, members of Delta Company, in a gesture of goodwill, arranged a Christmas dinner for the Croatian locals. Canaidan soldiers on the Serb side of the ceasefire line arranged similar feasts to retain the UN’s aura of neutrality. Cpl. Marc Kaipio of Thunder Bay, Onterio, dressed up as Santa Claus and handed out toys and candy to children.

“Christmas is the same all over the world,” he said. “The only difference is language.”

Army chaplains also kept busy, holding services in bombed-out churches for local residents and soldiers alike. “We pray together for peace,” said padre Lieut. Stephen Merriman of Victoria. “These people have never had a free Christmas. Last year, it was the war and before that the Communists. I just tell them to enjoy this Christmas in freedom.”

Life shattered for Croatians targeted in Serb missile raids

While fighting rages in Bosnia, Croatians are also embroiled ina territorial dispute with Serbs

By: Todd Bensman

St. Petersburg Times

SIBENIK, Croatia – Their injured bodies wrapped like mummies in red layers of gauze, Martin and Ana Reljanovic lie listlessly among tightly packed rows of wounded people in the subterranean bomb shelter of the local hospital.

They are only the most recent arrivals to this crowded ward, which offers protection against the rockets and artillery shells that routinely blast huge holes in the hospital’s upper floors. What happened to them rarely makes headlines outside Croatia, but it is a bloody scene that has been played out every day for the last 10 weeks in dozens of picturesque seaside towns along a thin, 100-mile swath of the country’s Adriatic coastline.

The problems started Jan. 22 when Croatian military forces violated a yearlong U.N. peace plan with an offensive to reclaim areas taken by Serbs in the 1991 Croatian war. The Serbs have retaliated with a low-intensity war of attrition involving irregular, seemingly arbitrary, bombardments of civilian populations.

The Reljanovics were working in their garden one day recently when Serb occupying forces in the mountains five miles away launched a rocket attack so suddenly that the authorities didn’t have time to sound air raid sirens.

An Orkan rocket – its warhead loaded with thousands of tiny bell-shaped cluster bombs – felled the couple as they were running for a neighborhood shelter.

“I can only remember a big explosion and saw all the little bells, and each one was exploding all around,” said Martin Reljanovic, 44, in a voice weakened by leg, arm and chest injuries. “Sibenik is like an insane asylum. Everyone is running around crazy.”

Government and U.N. officials can only speculate on how many casualties the bombing campaign has produced, or what the Serbs hope to gain by it. The psychological terror it generates has closed schools, shut down heavy industry, chased away tourists and forced residents to spend much of their lives in bomb shelters.

1992 Photo by Todd Bensman

“This is a dirty war,” said Pasko Bubalo, mayor of Sibenik, a city of 40,000 that was a tourist mecca before the war. “All the time they are pursuing their strategy to create panic. They only shoot at schools, markets and churches. Every day we have to sit as targets.”

The weeks of shelling are chipping away at more than the elegant Ottoman-era stone architecture of these coastal towns. Buildings and homes – even docked boats – are wrecked. Nervous pedestrians walk quickly past battlements and buildings protected by rows of logs. Rubble litters the mostly deserted streets.

The weariness many residents feel from the constant threat of violence from the sky, and the economic disruption that comes with it, is rapidly being replaced by anger – directed at the Serbs but also at the Croatian government for launching the January offensive that provoked them. The frustration is exacerbated by a strict system of electricity rationing imposed by the government after retreating Serbs blew up a major power station in January. Many families have simply moved away.

In the battered town of Vodice, 20 miles north of Sibenik and three miles from Serb positions, all but about 1,000 of the town’s 10,000 residents have fled. Ivan Juricev, a 41-year-old construction worker, is one of the few who remains. He sent his wife and three children to Split after a rocket blew away the upper story of the family’s home while everyone was downstairs.

In the several weeks since the bomb hit, Juricev has waited for a chance to start rebuilding, but incessant shelling has forced him to spend most of his days and nights in a neighbor’s basement, which is outfitted with beds, a television and VCR equipment.

The shelling has settled into a pattern. Juricev said he can count on rockets and artillery to come between noon and 1 p.m. and again at 7 p.m.

Still, at 1 p.m., Juricev was the only person to be seen outside. The town was deserted, made eerie by a strong wind howling through its ruins.

Standing amid the blocks of broken concrete littering his front yard, he said: “They shoot all the time. I just pray every day. But I don’t want to go. This is my house.”

There are signs that the low-intensity siege may end soon. Under growing pressure from his own people and the international community, Croatian President Franjo Tudjman last week agreed to return his forces to their pre-January positions on condition that Serbs in the region put their heavy weapons under U.N. control. The preliminary agreement was signed by representatives of the Serb leadership in Croatia but cannot come into force until the group’s self-styled parliament ratifies it.

In the meantime, the people who remain here will have to watch the ground as well as the sky. The small, unexploded bells scattered by the Orkan rockets are turning up with dangerous consequences – a child’s hand blown off one day, a car tire exploded the next. The bunkered hospital where the Reljanovics are recuperating is slowly filling up.

Pale from loss of blood, Mrs. Reljanovic was so angry about her condition she could hardly speak. Before nurses shooed away a visitor, she said, “I am angry at the whole world for refusing to understand what this war has been like. Is this what the world needs to figure out who is guilty?”

Cleansing’ also done by Muslims

By Todd Bensman

February 1993

VISOKO, Bosnia-Herzegovina – Serbs and Croats are not the only ones “ethnically cleansing” innocents in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Muslims, long painted as hapless victims of the republic’s other two ethnic groups, have become active members of the club.

One day recently Ruze Vujica – a 55-year-old Croatian woman – was happily going about routine life in her pastoral, predominantly Muslim village of Brestowsco; the next she was a panicked refugee fleeing a burning house without a husband or hope.

Vujica told her story, weeping, inside an abandoned school building in Kiseljak shared with 25 other Croatian refugees.

Muslim fighters swept out of the forest and seized Brestowsco in a surprise attack last month shortly after Croats and Muslims, once allied, turned their guns from the Serbs and against each other in central Bosnia.

The Muslim soldiers ordered all Croatians to leave, then looted and burned their homes. While the Croatian men regrouped to fight, Vujica and about 150 other women and children took refuge in the town’s Catholic church. Word reached Croat-controlled Kiseljak 10 miles away that the church was being mortared, and trucks arrived three days later to rescue them.

“I escaped with my children, but my husband is missing a leg and couldn’t walk. I heard he was taken prisoner,” sobbed Vujica. “We had good relations with the Muslims. It was strangers who attacked – not my neighbors.”

No civilians died in this “ethnic cleansing,” but the confirmed death toll from other incidents in central Bosnia is 300 and climbing. U.N. field officers assign blame for most of the dead to rampaging members of the Croatian Defense Council (HVO).

The officials say that outfit launched a coordinated attack across Bosnia to cement control over territorial grants provided under the proposed Vance-Owen peace plan, apparently thinking the deal will never be enforced. The plan would divide Bosnia into 10 semiautonomous provinces.

“The Croats seem to be pushing, shelling and cleansing from Prozor to Kiseljak,” said Maj. Brian Watters, deputy commander of the United Nations’ British Cheshires Regiment in Vitez. The Vitez region is the scene of notorious Croatian atrocities against Muslim civilians.

But nothing in Bosnia is that simple.

In this new war, the less well-armed Muslims apparently have launched a counter-cleansing campaign against Croat civilians, burning them out of decades-old mixed communities, according to the testimony of refugees.

In some cases, the ethnic cleansings of Croat citizens have occurred after Muslim militias issued an ultimatum to surrender their weapons.

A wounded Croatian man in a Vitez first-aid station said he organized an evacuation of Croatians from his town when he heard the ultimatum. The man, who would not identify himself, said he was on his way to negotiate a peaceful exodus when the Muslims attacked. “There was an explosion, and I was wounded,” he said, tears welling in his eyes. “My house was looted and burned because I was a Croatian.”

Even so, Muslim cleansing of Croats does not appear to be widespread. In many predominantly Muslim communities, Croats so far continue to live unmolested. Some, however, are getting nervous.

Visoko is a Muslim-dominated town of 40,000 people, of which only 5,000 are Croats. The town is only 10 miles north of Kiseljak, where HVO forces have pushed out virtually every Muslim and burned their homes. Those refugees went to Visoko with their tales.

“I am afraid, more afraid than a week ago,” said an 18-year-old Croatian woman who would only identify herself as Emily. “They are the majority. They can make us go. They do that in other places, in all places.”

Nevertheless, 63-year-old Marco Batina is optimistic.

“We’ve lived here together for years and they’ve never done us any wrong,” he said. “I think the Muslims who live here will protect us.”

Determining precisely what is happening is nearly impossible because the republic’s rural areas are partitioned and compartmentalized village by village. Propaganda and rumors are rampant.

“Villages are still being contested. It’s just more on an individual level of revenge in the hinterlands,” said Maj. Nestor Suarez, commander of a Spanish U.N. contingent in the Muslim-controlled town of Jablanica. “There are lots of uncontrolled factions in the Muslim forces. The more radical factions often provoke confrontations.”

U.N. officials in the field, however, say they have little evidence of Muslim forces perpetrating bloodly atrocities like those committed by Croats in Vitez. British troops there recently found the bodies of 60 Muslims shot to death in a local mosque and seven charred bodies of a family burned to death in a house. Mutilated bodies of Muslim civilians are still turning up daily.

KOSOVO

On background: In November 1992, I traveled to the southern Serbian province of Kosovo and on two separate occasions slipped in clandestinely with the aid of local Albanian activists to report on conditions that would, eventually, lead to a United States-involved war. In Kosovo, I saw firsthand how a small ruling minority – the Serbs – systematically oppressed and abused the majority Muslim Albania population. Even then, I heard rumblings about a shadowy armed group called the Kosovo Liberation Front, which would later rise to militarily oppose the Serb army. I traveled the province widely, saw underground university classrooms and interviewed the passivist Kosovo leader Ibrahim Rugova twice. It would be no surprise to me that years later, in 1999, war would break out.

In Kosovo, apartheid-like racial strife may descend into war

Bitterness between ethnic Albanians, Serbs may push Balkan war into Turkey, Greece

By Todd Bensman

Special to The San Francisco Examiner

November 15, 1992

PRISTINA, Kosovo – Selim Lula wants to kill Serbs – even the ones who were his classmates just one year ago.

While Serbian students still study in Pristina University’s spacious campus facilities, Lula and roughly 50,000 other ethnic Albanian students and teachers were abruptly expelled by government decree in October 1991.

Defiantly, they set up an illegal shadow university, cramming into tiny clandestine classrooms in safe houses scattered throughout the city.

Random police harassment, fear of arrest and a dwindling supply of banned Albanian-language textbooks make learning a daunting struggle.

“The only way to get out of this is with war,” said Lula, emerging from a small brick building with sheets draped carefully over the windows. “There is no other future without coming to that extreme.”

At the university on the other side of town, a Serb who would identify herself only as Leilah said she was pleased the Albanians were gone from the university.

“They are completely different – they’re dirtier than us,” said the 19-year-old dentistry student. “They don’t take care of themselves. They’re like gypsies.”

Like South Africa

A separation of ethnic Serbs and Albanians – similar to South Africa-style racial apartheid – has settled not just over student life but across the whole spectrum of Kosovo society, creating a crackling friction with international implications.

Alarmed at the degree of animosity between Serbs and the unarmed Albanians, international observers warn either side could provoke a spate of Bosnia-style “ethnic cleansing.” This would threaten to spread the Balkan war into neighboring countries of Albania, Turkey and Greece.

With the war in Bosnia seemingly winding down, as Serbian and Croatian forces consolidate their grip, Albanian leaders worry the Serbs are preparing to turn their attention to Kosovo.

If the situation does not relent, the war is likely to come here next,” said Ibrahim Rugova, who was the elected head of the illegal Albanian government last May. “We are practically under occupation.”

The separation of Albanians and Serbs into embittered camps living side by side was the outcome of hard-line Serbian President Slovadan Milosevic’s aim to reclaim Kosovo for Serbs. Serbian nationalists consider this southern province between Macedonia, Albania and Montenegro the spiritual and historic fatherland of the Serbian people.

16 years of self-rule

The mostly Muslim Albanians make up 90 percent of Kosovo’s two million people. They had enjoyed 16 years of self rule until the break-up of the Yugoslav federation prompted Albanian calls for independence. But such aspirations ended abruptly in July 1990 when Milosevic, ostensibly to protect the Serbian minority, declared martial law there.

“As privitization began in 1990, the Albanians controlled the administration of the economy and everything else,” explained Milosh Simovic, the appointed Serbian governor of Kosovo. “We had to enforce this state of emergency because they were destroying everything.”

Serbian police, armed with machine guns and backed by thousands of Yugoslav army troops, have enforced the purging of Albanians from government, the state-owned Pristina Hospital, factories, courts, theaters, the media and schools. Serbs have taken over management positions and jobs.

According to the Albanian Human Rights Council, more than 40 percent of the Albanian population has been left without legal means of support.

Albanians have set up their own low-cost medical clinics, high schools, black-market businesses and even a parliamentary-style shadow government that is tolerated because it commands no army.

Many Albanians are convinced the Serbs are trying to pressure them to leave, a bloodless precursor to more violent ethnic cleansing.

“Already, 200,000 Albanians have left,” said Hydajet Hyseni, vice president of the Albanian Human Rights Council. “The social situation is becoming intolerable. People are beginning to lose patience, and the consequence will be the start of a conflict that would be catastrophic.”

Rugova said his underground government was playing for time. He preaches a policy of passive “Gandhian” resistance while appealing to the world for military intervention – pleas that so far have gone unanswered.

He concedes that he may not be able to prevent the frustration of many younger Albanians from boiling over into acts of insurrection that could provoke a violent Serbian response.

“Our only alternative is to have a policy of endurance,” he said. “Even though it is difficult to keep it going because of the suffering.”

In Macedonia, look – don’t fight

TODD BENSMAN

Special to USA Today July 4, 1993

SKOPJE, Macedonia – The last assignment the U.S. Army gave Maj. William Almas brought him face to face with exploding Scud missiles in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.

The Tampa native spent 11 months in the Middle East during the Persian Gulf crisis as a procurement officer.

Now the Army has sent Almas to Macedonia, where he and 325 other American soldiers will stand face to face with Serbian soldiers as part of a United Nations force trying to keep the Balkan war from spreading south.

In Skopje, the capital, the 38-year-old Almas hopes the next six months are more sedate than his gulf war experience.

“If the definition of boring means no Scuds coming at you then that’s okay,” he said. “It’s just another assignment, and that’s good enough for me.”

Almas, a stocky man with a black crewcut and aviator’s sunglasses, is one of 10 members of an American team sent here to gather supplies and equipment for the main American infantry force due to arrive by mid-July. A second, larger advance team is due this week.

When the bulk of U.S. Army troops land in this threatened ex-Yugoslav republic, they can expect a major departure from the kind of shoot-to-kill soldiering for which they were trained. The Americans will not pound recalcitrant warlords, storm deserts or even take orders from their own officers. Instead, the lightly armed troops will observe Serbian military activity passively from 23 border posts as part of a United Nations force.

So alien is their new duty that the Americans will have to undergo two weeks of retraining in peacekeeping duty before they go to the field.

“We will do whatever the U.N. commander asks us to do,” said Maj. Len Jeffery of Houston, a U.S. Army spokesman in Skopje. “This is a U.N. operation.”

According to Gen. Caermark Thompson, the Danish U.N. officer who will command the U.S. troops, the Americans are to be integrated as a reserve force into the 700-man Nordic battalion that has monitored Macedonia’s mountainous 105-mile-long border with Serbia since October.

The American infantry will spend the next six months making routine foot patrols of the border area to observe three Serbian armored divisions just across the border.

“You will see the Americans patrolling and manning these posts to show the U.N. is present,” Thompson said Thursday. “We are not a protection force. We are not going to protect the Macedonians. We will monitor and report.”

Most of the Americans, like Almas, will come from the 6th Battalion’s 502nd Light Infantry Brigade based in Berlin. The Americans already in Skopje are preparing to receive an advance party of 30 early this week.

The balance of the force is expected to deploy by Hercules and Galaxy transport planes over three days in mid-July. They will come equipped with 14 armored personnel carriers, Humvee all-terrain vehicles, heavy machine guns and anti-tank TOW missiles, American officers said.

Duty in Macedonia may be quiet, but it is not without risk.

Serbia refuses to recognize the borders of Macedonia where Americans will patrol.

Last week, Serb soldiers captured then released three U.N. soldiers on patrol, and U.N. officials report that eight Serb soldiers recently took up an aggressive stance against Norwegian soldiers. The situation was defused without incident.

For the moment, this tiny nation of 2-million people nestled among Greece, Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria is quiet while Serbs wage war in Bosnia. But observers fear Serbia could launch an ethnic-cleansing campaign against the Albanian majority in its southern province of Kosovo, which is adjacent to Macedonia, once the Bosnian war dies down.

Macedonia, which declared independence from Yugoslavia in September 1991, is regarded by some elements in Serbia as “southern Serbia” because of historical territorial claims. Some observers fear that war in Kosovo could set off a chain reaction of animosities leaving Macedonia occupied and drawing in Albania, Greece, Turkey and Bulgaria.

President Clinton last month opted to send the Americans here as part of a “containment” policy. But the introduction of American military forces in the Balkan theater is seen here more as a symbolic message to Serbia than a viable defense of Macedonia. The Americans’ ability to actually shoot will be sharply limited by the U.N.’s rules of engagement, and U.N. officials say Serbia’s 40,000 well-armed troops and warplanes could overrun the U.N. force and Macedonia’s poorly equipped 10,000-man army in three days.

“The American presence has nothing to do with defending this area.

It’s a strong political message, very symbolic,” said Janusz Sznajder, the U.N.’s chief of civil affairs and liaison officer to the Macedonian government. Clinton has not elaborated on what steps he is prepared to take to enforce his containment policy, but the deployment has raised expectations and hope among Macedonians.

“An American presence will bring Macedonia under American influence. It could be a tripwire for future deployments,” said Alexander Damovski, a journalist for the New Macedonian, the leading newspaper in Skopje. “It’s just the beginning. The Serbs know that. It will be an effective deterrent.”

For their part, trading guns for binoculars is not exactly what the Americans had in mind when they joined the military. But many of the soldiers already here say they are prepared to adapt to the slower U.N. pace. As a procurement officer, Almas – whose wife, Joyce, and two children, Laura and Sean, are in Germany – says he is facing a system less sophisticated than the American one he used in the gulf war.

“I did the same thing in Saudi Arabia, but here it’s going to be a real learning experience.”

Almas’ mother, Caroline, who lives in Tampa, said her fears have changed since his Persian Gulf duty. “While he was in Saudi Arabia my fear was that he would be gassed or captured. . . . Now I worry about the ambushing and disease . . . or that he might be in the wrong place at the right time.”

She said he attended Jesuit High School, where he earned an ROTC scholarship, and the University of Tampa.

“He’s proud to serve for his country . . . and he goes with honor,” she said.

Seen enough, Canadian peacekeepers say:

April 22, 1993

Todd Bensman

The Vancouver Sun

TUZLA, Bosnia-Herzegovina – The seven Canadian soldiers had a weariness about them that went far beyond their rough day-long journey from the shattered eastern Bosnian town of Srebrenica.

For 40 days, they were posted in Srebrenica, witnessing the closing convulsions of a year-long Serbian siege of the Muslim enclave.

In two weeks, all seven will be in Canada after a six-month tour of peacekeeping with the Royal Canadian Regiment’s 2nd Battalion.

After drinking good beer and eating several courses at the Hotel Tuzla dining room Tuesday, they relaxed in the lobby.

“We’ve seen enough. It’s time to go home and tend our own lawn,” said Pte. Mike Jeffers of Kingston, Ont.

Casualty evacuation was the worst, they said.

“I worked in a hospital before starting my career in the army,” said Pte. David Bush, a machine-gunner from Wabamun, Alta. “But you never see anything like this – people lying around with open wounds and half their heads missing.”

The seven Canadians were in the first UN contingent sent in to set up a command centre for a relief and evacuation operation. But until a truce last Sunday, the encircling Serbs obstructed attempts to relieve the town, shelling it often.

On Easter Monday, thousands of artillery rounds hit the city, including an elementary school sheltering refugees.

The Canadians removed the wounded under a rain of shells by loading them on top of their armored personnel carriers.

“A woman took shrapnel right behind me,” said Cpl. Walter Postma of Hamilton. “If she had not been there it would have been me. We had to pick her up. There was dirt flying everywhere and there were so many explosions all around us that our ears were ringing.”

“The kids were the worst,” said Pte. Chris Sharron of Windsor, Ont.

“There was one kid there with his head blown open. I cannot forget seeing the dead people. They just lay there all yellow with their eyes open, staring up at you.”

Said one soldier: “We miss Canada. We are coming home and not looking back.”