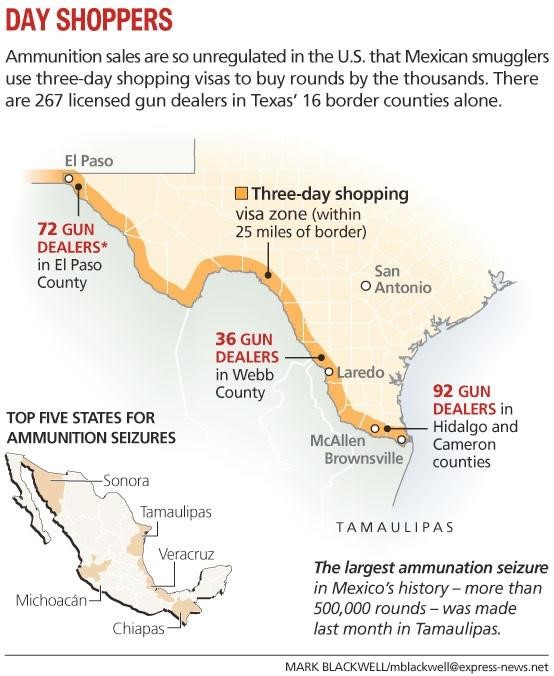

So loosely regulated and available is American ammunition that Mexican smugglers are simply dropping over on day shopping visas to cruise a bounty of stores within the 25-mile deep commercial zone where they can legally wander. Judging by prosecutions and seizures, the day-trippers are doing their part to bring home huge quantities of bullets. The one law that applies to ammunition purchases doesn’t hinder much. It requires that buyers be U.S. citizens. But retailers aren’t required to check. So it’s don’t ask, don’t tell.

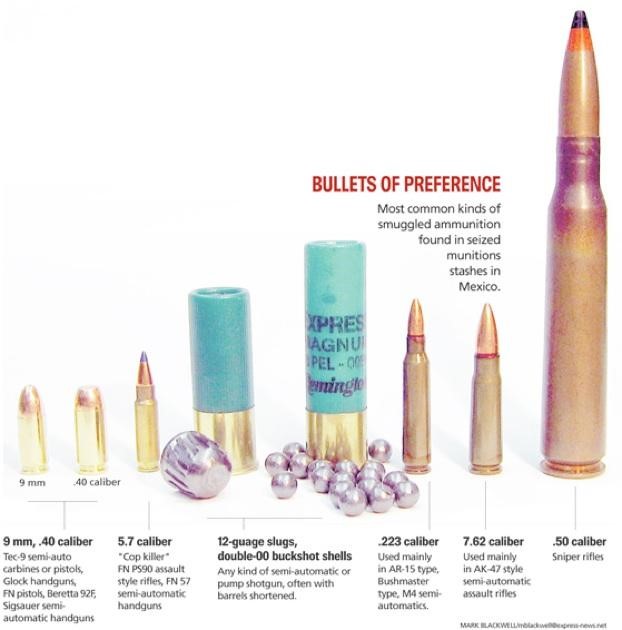

MCALLEN, TX. — So popular is the 7.62 caliber ammunition for AK-47 semi-automatic assault rifles that one Academy Sports and Outdoors in this border city stacks shoebox-sized cases several feet high down half a row in the hunting section.

Employees like Francisco Rodriguez, who works in the guns and ammo section, are not short of stories about men piling shopping carts high with the $74 cases of 7.62 caliber rounds, as well as clearing shelves of .9 mm rounds and other ammunition that fits semi-automatic assault-style rifles. Several employees of a number of other South Texas stores say customers routinely pay thousands in cash and simply wheel the stuff out, no questions asked.

“I had a guy come in the other day and clear me out of .223s,” Rodriguez said of ammunition that fits assault-type rifles as well as classic hunting rifle styles. But unlike a typical hunter, this customer “paid $5,000 cash, and then he went to one of our other stores and cleaned that out, too. I didn’t ask what he was going to do with it. He probably was going to take it to Mexico.”

The market for certain kinds of ammo is so robust these days that Texas-based Academy created its own box brand, Monarch, filled with Russia-made AK-47 bullets. Some smaller independent stores report being unable to keep up with demand for .50 caliber sniper rifle rounds, which can sell for $4 each. The bullet business is booming all along the border.

There is nothing illegal about buying or selling large amounts of civilian-use ammunition to just about any adult in the U.S. Bullets are a commodity almost as unregulated as milk or bread, with no record keeping requirement, limit on volume per individual, or disqualifying criminal history for buyers, unlike some rules governing the sale of guns. Also unlike guns, bullets don’t have serial numbers that can later be traced to a store or person.

All of this is a big problem, according to Mexican government officials. Mountains of ammunition types so popular at Academy stores in Texas border cities keep turning up across the Rio Grande in drug cartel weapons depots also full of American-sold assault-style rifles. The millions of rounds found in these depots have been smuggled to Mexico, where they are illegal, and authorities on both sides squarely peg U.S. retailers as the source.

So loosely regulated and available is American ammunition that Mexican smugglers are simply dropping over on three-day shopping visas to cruise a bounty of stores within the 25-mile deep commercial zone the visas allow them to wander. Judging by prosecutions and seizures, the day-trippers are doing their part to bring home huge quantities of bullets.

The one law that applies to ammunition purchases doesn’t hinder much. It requires that buyers be U.S. citizens. But retailers aren’t required to check. So it’s don’t ask, don’t tell.

American law enforcement authorities, under pressure from Mexico, are already escalating a push to slow the guns bought from U.S. merchants and used by drug gang paramilitaries to help kill more than 5,000 Mexican citizens, police and government officials. But in the last year or two the Americans and Mexicans also have begun focusing on their less prioritized central ingredient: bullets.

“The main thing is for us to stop the illegal flow of guns going to Mexico, but if they don’t have bullets they can’t use them,” said J. Dewey Webb, the Houston-based head of the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “It’s just as important and it’s just as illegal. If we could reduce the traffickers to throwing rocks at each other, I think we’ve achieved our goal.”

Authorities believe one of the nation’s busiest ammunition smuggling corridors runs through South Texas because of a proliferation of stores in the densely populated regions close to the Mexican border. That pipeline, they say, runs along state highways 77 and 281 through McAllen, Harlingen and Brownsville. The connecting Mexican state of Tamaulipas is listed as one of the top five Mexican states for illegal ammunition seizures, according to the attorney general’s office.

Those who speak for large retailers, as well as small private ones throughout South Texas, don’t like to contemplate the prospect of profiting from Mexico’s tragedy. Instead, many of those interviewed by the Express-News posit that mainly target-shooting hobbyists are the ones buying out stocks of 5.7 “cop killer” rifle bullets that, fired from certain concealable handguns, can puncture police armor, or .50 caliber rounds that slice through buildings.

Academy, which shows up in smuggling prosecutions as a source of weapons, refused to cooperate with this story. Pressed, a spokesman would not address whether any policy calls for voluntary record keeping or self-regulation for ammo sales, as some stores do with guns. Academy’s refusal to discuss the issue came the same day last month as a huge weapons seizure just a few miles away over the river in Reynosa.

The Mexican army uncovered a cartel weapons stash so large it held 500,000 bullets for any of the 540 firearms also found. Mexico’s attorney general’s office says three million rounds have been seized nationally in just the last 24 months.

Because of the absence of mandatory or voluntary controls on ammo sales, agents hunting the trail of smuggling-minded shoppers will remain hard pressed to cut this gusher of a supply line.

Don’t ask, don’t tell

Kirkpatrick Guns and Ammo resides in a shopping district on the north side of Laredo. On Nov. 1, 2006, two Mexican men in town on three-day shopping visas were sitting on the store floor sorting their purchase of 12,570 live rounds of assorted ammunition when their luck ran out. In through the door walked off-duty ATF Special Agent Frank Arrendondo to do some personal shopping.

After ascertaining that the men weren’t U.S. citizens and had just bought the ammunition, the agent arrested Carlos Alberto Osorio Castrejon and Ramon Uresti Careaga on the spot. The two men later confessed that they’d made other day trips for American ammunition to take with them back to Mexico, like two purchases the previous month at another local store where they paid $6,193 in cash.

They said they’d had those loads driven back across the international bridge hidden aboard a tractor-trailer rig. At the time, Nuevo Laredo gun battles between rival drug cartels were leaving bodies strewn through the streets. Last year, both Mexicans pleaded guilty and got 15 months in prison each. Kirkpatrick was never on the hook.

The bust illustrates how easily ammunition trafficking is accomplished and why American retailers can go on profiting by it with little legal risk while bullets fly almost daily a few miles away in Mexico.

Longtime Kirkpatrick manager Maria Elena Gonzalez, when asked about bullet buyers who pay cash, said she almost always makes sure her monolingual Spanish-speaking customers present some proof of citizenship to comply with the one law.

“I always ask, ‘Are you from here?’.” she said. “If they say, ‘Mexico,’ it’s ‘Oh, I’m sorry.’.”

But when reminded of the Osorio and Uresti ammo smuggling case in her store, Gonzalez said she wasn’t there that day, her boss was. Storeowner Bill Kirkpatrick said he doesn’t ask and nothing in the law says he has to.

“On ammo, we don’t ask, because a lot of people can get offended,” Kirkpatrick said. “It’s politically incorrect, like you’re calling them a spic.”

With thousands of dollars in cash on the counter, it’s easy to see why retailers might not feel curious. But federal prosecutors warn that “prudent” ammunition sellers would be wise to start becoming curious.

“Ultimately,” said San Antonio-based Assistant U.S. Attorney Richard Durbin. “the seller’s state of mind would be a question of fact for a jury to resolve.”

Still, Kirkpatrick said the bust in his store and violence in Mexico has him voluntarily limiting volume bullet sales to people he knows. These are usually wealthy local firearms enthusiasts who like target practicing with assault-style guns. One hobbyist, he said, recently cleared out his .50 caliber bullets for some fun at the range with an $8,000 sniper rifle he’d bought from Kirkpatrick.

He said one of many legitimate explanations for why local gun hobbyists buy large amounts of ammunition is to hedge against rising prices. After all, target practice with those kind of guns can eat up a lot of expensive rounds. Kirkpatrick said he’s sure his socially conscious restraint ensures none of his bullets feed Mexico’s drug wars – pretty sure, anyway.

“The gun stores,” he assured. “just have to police themselves.”

A higher social good

That retailers like Kirkpatrick would voluntarily turn down legal profits for a higher social good is not without precedent. In the early 2000s, national retailers like Walgreens and Target began setting voluntary limits on the sale of common cold medicines used to make illegal methamphetamine to dampen the contagion. Texas and other states eventually passed laws restricting volume sales. In October, President Bush signed the Methamphetamine Production Prevention Act, requiring retailers to log sales of cold medicines as a means to help law enforcement and deter meth producers.

“I do see a parallel,” said East Texas-based Assistant U.S. Attorney Kevin McClendon, who in 2004 filed a civil lawsuit against Walgreens seeking to force compliance with sales reporting rules. “If the abuse of the sales offends the public enough, I could see restrictions going that way with ammunition sales too.”

But for gun store retailers along the Texas border who may feel socially conscious, the incentive to keep selling is seductive.

Back at Academy stores in McAllen, employees said they routinely sell large quantities of ammunition to cash-paying customers even when they suspect it’s to be smuggled. They said they’re unaware of any policy about self-restricting sales.

“A young woman came in the other day and bought 75 boxes” of 7.62 caliber Monarch brand bullets” for AK-47s, one employee said. “She said it was for her father’s birthday. Um…okaaaay.”

Austin Ortiz, manager of the firearms section in a newly opened Academy in McAllen, said the 7.62 and .223 calibers are among his best sellers. There were no company instructions to call the ATF or check for citizenship on suspicious buyers, he said.

“There are a lot of gun ranges around here,” Ortiz said. Asked if he thought smugglers also were buying, he didn’t hesitate.

“I’m pretty sure there are people out there who will take it over and sell it at a profit.”

A most elusive contraband

On the Laredo side of the international bridge one recent day, a special mobile team of U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents had set up shop. American customs officers mostly work the northbound vehicular traffic coming out of Mexico. But this team goes against the grain.

Its members randomly pulled over a small percentage of cars, trucks and busloads full of people headed south into Mexico. On Dec. 11, officers found one of the items they look for a lot more these days, given Mexico’s grim situation: contraband ammunition. Some 300 rounds, plus pistorl and assault rifle magazines, were found secreted in the compartment of a 2000 Ford Expedition driven by Raul Alvarez, Jr., the manager of a bordello in Nuevo Laredo.

Just weeks earlier, the Express-News had featured Alvarez in a story for this series as having bought and sold guns that wound up at the scene of a brutal ambush murder of four police officers in Aguascalientes, Mexico. He’d offered up an improbable story absolving himself of ever trafficking in munitions.

But the secret compartment of Alvarez’s vehicle filled with bullets and clips suggested to them he is indeed a smuggler. He is facing up to ten years in prison if convicted.

The CBP southbound inspection teams offer one of the U.S.’s only weapons against ammunition smugglers. And it’s a continuous game of cat and mouse where the mouse mostly wins.

Whereas guns recovered in Mexico can at least be traced to a store and original buyer, bullets leave no trail. Smugglers eliminate any last clue by removing the rounds from coded store boxes. Bullets are considered too heavy to swim or hike into Mexico in profitable enough quantities. So shells usually go into secret vehicle compartments and driven in the direction everyone knows gets less attention – south.

Three teams on any given day show up at any of the Laredo area’s six different border crossings, to keep the drug cartel spotters off guard. They use hand-held X-ray gear that can see through car panels and fiber optic scopes that can look down gas tanks. Recently, a new tool was added: a dog named Lucy trained to sniff out ammunition.

But with dozens of international gateways, the Texas teams are mathematically and geographically disadvantaged. On this day, neither Lucy nor her CBP partners found any southbound ammunition at the main Laredo passenger bridge to Nuevo Laredo.

But on the other side of the same crossing, a grim-faced Mexican army officer who wouldn’t be identified said his machine-gun toting squad found a massive stash of guns and ammunition in a pickup that had gotten through the American dragnet.

The lucky discovery exemplified the hit-and-miss nature of new efforts on both sides to troll for ammunition. The CBP team strongly suspects the 155 ammunition seizures made in 2008 in the busy Brownsville to Del Rio sector made hardly a dent.

“The reality is that the smuggler has the advantage over us,” conceded CBP Assistant Port Director Jose R. Uribe. “It’s just the nature of the border.”

Dumb luck is the regular, if unreliable partner in these efforts. An American agent has to somehow catch physical sight of a smuggler or catch them in the act, like at Kirkpatrick Guns.

For instance, in November 2006 El Paso police officers just happened to spot two Mexican men driving into an alley behind Alamo Shooters Supply. They followed and watched the men cart out dollies laden with tens of thousands of rounds. Javier Paredes Vega and his brother Jorge Paredes Vega admitted they were regular ammo smugglers who made profitable use of their day visa privileges. Last year, both pleaded guilty to weapons violations.

In a different El Paso case this year, a lucky tip from a sympathetic gun store owner led agents to roll up a well-oiled ring of bullet smugglers who’d been responsible for sending up to 80,000 rounds back to Mexico.

The deployment of Mexican army units at major border crossings is new. Their role is singular: to increase the odds of searching incoming vehicles only for American guns, ammunition and explosives.

But observation of several of those military units showed their checks usually amount to hand knocking along the sides of vehicles to check for the sound of hidden compartments. They have none of the equipment their CBP counterparts use, let alone ammo-sniffing canines. Both sides, though, have no choice but to let some less trammeled crossings go untended.

The Los Ebanos International Ferry about 30 miles west of McAllen is one of the last hand-pulled boat rides the 75 yards across the muddy Rio Grande. Old-style, Mexican deckhands strain on pulley ropes to slowly move three or four vehicles at a time over the river. On a recent business day at the ferry crossing, only a couple of white-uniformed civilian customs officials were stationed on the Mexican side.

Sometimes they glanced into back seats or opened a trunk for a hands-off look inside. On the American side, no one was checking southbound vehicles that day. But smugglers of all kinds know this place well.

One of the rope pullers, Alejos Flores, 66, said the narcos offer him thousands to rent his small blue rowboat on a riverbank.

“They’re not crossing watermelons,” Flores said, explaining why he’ll keep rope pulling for a living. “I learned a long time ago that if I don’t put my hand in the fire I won’t get burned.”