In Juarez, confirmation that Trump’s Remain in Mexico policy is driving asylum claimant decisions to return home. In two Juarez city shelters, a Honduran mother of two children, a young single Honduran woman, and a young single man from Guatemalan say they’re going home rather than to lose the prospect of living illegally in the United States.

CIUDAD JUAREZ, Mexico – The New York Times is crediting President Donald Trump’s last set of policy tries for – at long last – a precipitous drop in illegal immigration from Central America. Specifically, the newspaper cited a highly deterring double play by Mexico, prompted by President Trump’s arm-twisting.

By Todd Bensman as originally published by the Center for Immigration Studies July 22, 2019

One credited play was Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, formally called the Migrant Protection Protocols, where U.S. immigration sends asylum claimants to wait for their hearings in Mexican cities like Juarez rather than the incentivizing prospect of waiting inside the United States, where they can count on living for years illegally if their claims fail. The incentive of living in the U.S. illegally evidently has been turned off because failure of claims means the migrants instead have to live in Mexico, and will not join America’s swollen population of illegal millions who can’t be effectively tracked down and deported.

Last week in Juarez, I was able to confirm, at least anecdotally, how the Remain in Mexico policy is influencing the thinking of asylum claimants and driving decisions to return home. In two Juarez city shelters I was able to visit, a Honduran mother of two children, a young single Honduran woman, and a young single man from Guatemalan told me that they and most of the hundreds of similarly situated returnees around them had no intention of waiting in Mexico for distant U.S. court hearings they may lose along with the prospect of living illegally in the United States.

All planned returns to their supposedly intolerable home countries. No one seems to have numbers to show how extensive this trend is among the estimated 20,000 Central Americans returned to wait in Mexico. But this trend apparently is discernable enough that the United Nations’ International Organization of Migration is organizing free bus rides for the returnees to go back to their homes in Central America.

I’ll get to all of that after a quick aside.

As I was writing this in my El Paso hotel room Friday, an active-duty Border Patrol agent called to tell me an order had just come down throughout the sector by which Central American family units would no longer be subject to the Remain in Mexico policy. All are, once again, to be waved through to the U.S. interior to await the outcome of their asylum claims, again with the prospect of living on indefinitely as illegals if they lose. I’m still waiting for responses to my official inquiries about this order, but in the meantime, here’s what the Border Patrol agent told me:

“This is so upsetting; we were barely starting to get back to work,” the agent complained. “It’s just sooo ridiculous. Something’s working and then it’s like, what? It’s working too efficiently, so let’s not do that?”

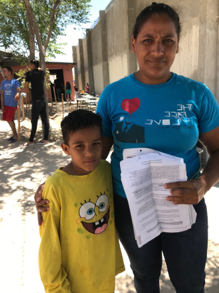

Here’s how the policy has been received by those subject to it. Take Veronica Janeth Tejeda of LLoro, Honduras. CBP dropped her and her 14-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son in Juarez a couple of days after they swam the Rio Grande and turned themselves on asylum claims like hundreds of thousands of their fellow citizens before them who succeeded in entering the United States. I found them in a Juarez shelter about a half mile from the border, in clear view of El Paso.

Ms. Tejeda told me she set out for America six weeks earlier with her children because she “heard on the news that mothers and fathers who had kids were crossing in to the United States. I was told the people from immigration control were going to find us and take care of us, that they were going to take our information and just let me go into the United States.”

This was a reasonable expectation, since hundreds of thousands had done just that on asylum claims based on claims of terrible tortures awaiting them back home.

Instead, Ms. Tejeda’s timing was unfortunate because Remain in Mexico had temporarily cleared a legal challenge and was in effect when she crossed. Instead of starting a shining new life as a permanently illegal alien in America, she and her children found themselves sitting it out in a dusty Juarez church shelter that had taken in about 90 similarly situated migrants. She had an American document that said her first court hearing was September 19, 2019, two months away.

The deterrent impact of the Remain in Mexico policy is evident in Ms. Tejeda’s expressed sentiments, which she will take home with her.

“If I knew before that things were going to be like this, I never would have left the country.”

What also must be underlined at this juncture is the broad U.S. media reporting of persistent claims by the migrants and their many U.S. advocates that life in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador is intolerable with gang violence and poverty. One would have to believe, based on those claims, that almost any other country, to include many parts of Mexico or safe wonderlands like Costa Rica, would be preferable to the almost certain death and bodily harm that are always purportedly imminent in those countries.

Yet Ms. Tejeda said she is going home to Honduras on the first UN bus that can be arranged, rather than to wait 10 weeks for a hearing she would likely lose while outside of the United States. Keep in mind that Ms. Tejeda, were she to lose an asylum claim as do almost all Central Americans, would be stuck indefinitely on the outside in Mexico, whereas a win or loss would not matter if she were inside the United States. Hundreds of thousands, after all, evade deportation for endless years, and everyone knows this. Some 950,000 illegal immigrants live inside the United States with deportation orders and having lost appeals for asylum and all manner of other permission to stay.

But for Ms. Tejeda and the others I interviewed, the only acceptable outcome was the prospect of indefinite economic opportunity of America available to her, win or lose in court. Not the prospect that she might find safety in other parts of Mexico, Costa Rica, or … Argentina. She was going home to a country that is always said to be a terrifying wasteland.

“I just want to go home and find a job in Honduras,” she said, simply.

She was hardly alone is deciding to return to unlivable wastelands.

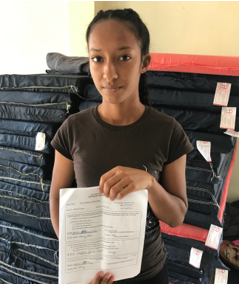

Gaixania Reyes, a 22-year-old Honduran, said her decision to trek to America was entirely based on a desire to achieve “the American dream,” not any kind of terrible violence. She said she became acutely aware, through the local media and from those who left before her, that almost her entire village had made it over the border at ports of entry into the United States, had been waved through, and would live happily ever after, with legal permission or not. Sure, parents with kids were achieving immediate release into the United States on a grand scale, but she heard that even huge numbers of Hondurans without children, like her, were getting the pass-through treatment.

“I really thought I would make it in because so many people crossed and got a better life,” Ms. Reyes told me. “Thousands left my town. The schools were empty. No kids. No parents. Everybody was saying I can cross with kids, but I don’t have any kids. So I crossed over the river.”

The release part of catch-and-release wasn’t to be for her, though. CBP flew her on a plane with a large group of other migrants to El Paso, then put everyone on vans and dropped them off in Juarez. She sits now in the Juarez shelter with a paper that says her court date in America is December 17, 2019, five months away. The juxtaposition of reality against expectation was angering.

“I didn’t expect that,” she said angrily. “I think these papers are a joke! They played with our sentiments and all they did was gave us these papers! When I came here and saw this, I realized they just want to run us off.”

Clearly, for Ms. Reyes too, it was the American dream or nothing, not a place safer than Honduras. Ms. Reyes knew she likely would never be admitted into the United States after the December 17 court hearing and that if she lost she would still not be in the United States able to live illegally.

But rather than start a new life in many of the safer provinces of Mexico, or Costa Rica or any other country of Latin America, Ms. Reyes too said she is heading home to Honduras “as soon as possible” on one of the UN buses. She seemed to understand that if her hearing didn’t go her way, she wouldn’t even be able to live indefinitely as an illegal alien in the United States.

“I’ve suffered enough, and I don’t want to suffer more for a waste of time” by losing her U.S. hearing while in Mexico, she said.

It was pretty much the same story with Guatemalan national Jose Luis Funes. Speaking through a chain link fence at the Casa Del Migrante in southern Juarez, he explained that the Americans also sent him to wait in Mexico. Most of the 700 migrants at the shelter were in a similar situation and were all planning to go home, he said.

“I’m not going to get asylum,” he said. “I’m going back.”

At issue now, since my Border Patrol agent source brought it up, is whether the policy is being pulled back from Central American families like Ms. Tejeda.

Surely if Ms. Tejeda was aware that she could live in America with her children, win or lose at court, she would not board that UN bus to Honduras. She would head straight for the border again, no doubt followed by another 100,000 a month from her country.

Follow Todd Bensman on Twitter @BensmanTodd