Thousands of “extra-continental” migrants from troubled hot spots all over the world are arriving at the U.S. border. Escaping analysis is that some nations are home to militias conducting unspeakable brutalities, as well as violent criminals, Islamic terrorist groups, and murderers on various sides of armed rebellions, economic collapse, and civil wars. Is homeland security vetting them? Bensman traveled to Mexico to meet Africans.

By Todd Bensman originally published by the Center for Immigration Studies on on August 23, 2019

CIUDAD ACUÑA, Mexico — Few Hondurans, Guatemalans, or El Salvadorans inhabit an encampment of makeshift tents amid the detritus of roughing it in a public “ecological park” here, just 150 yards from the Rio Grande and the American Dream. Central Americans have commanded almost all national attention and policy effort to slow their engulfing arrivals this past year by the hundreds of thousands.

But largely escaping notice, let alone any homeland security focus, is another kind of migrant, represented by the roughly 200 aspiring asylum seekers in the camp here who speak a Babylon of non-Latin languages.

Among them was a Russian who is emblematic of the need for American homeland security agencies to find some way to take pause with these migrants and vet their backgrounds rather than lumping them into masses of those who are being quick-released into the United States to await distant immigration court dates.

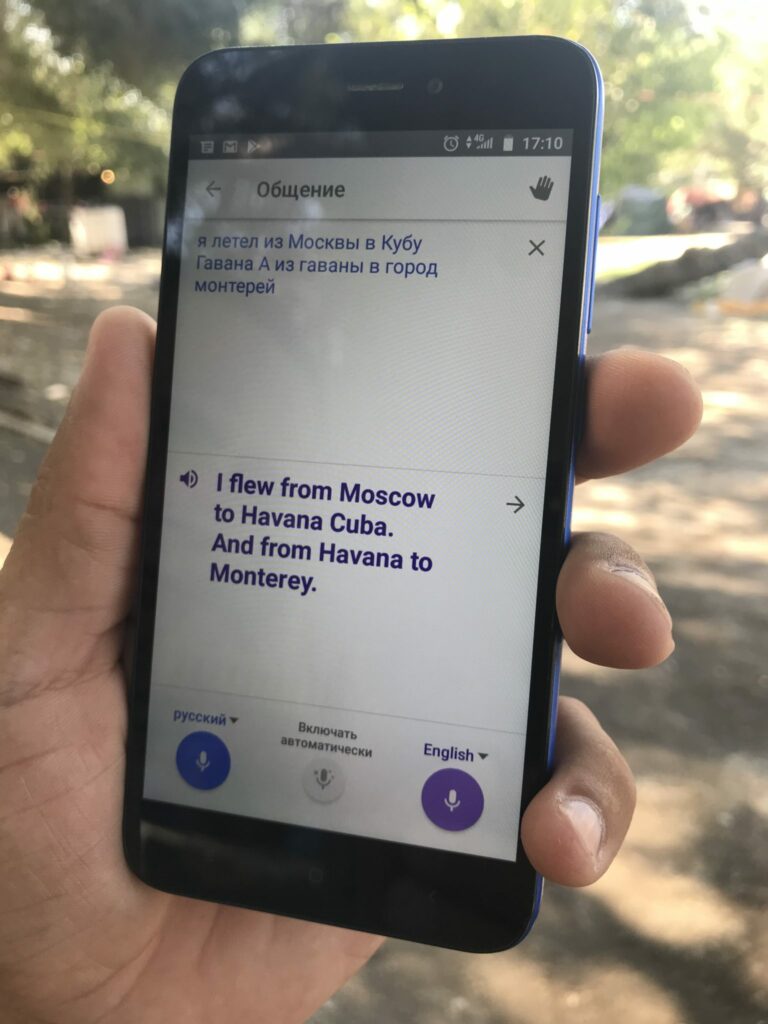

Through a phone translator app, the Russian would only give his name as “Vladimir” and his home as the city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk on Russia’s Sakhalin Island, just north of Japan.

In responding to a question about why he left home and chose the U.S. southern border as his entrance point he would only answer: “Problems with the police.”

He would not elaborate other than to suggest that whatever happened felt like persecution to him.

“I had to leave,” Vladimir said of his mysterious law enforcement issue.

He said it was easy and cheap to travel alone here, without smuggling assistance or breaking any laws, that many Russians were making the trip, and that they all spoke to each other on social media. A flight from Moscow to Havana, Cuba, on a cheap visitor’s visa, then a flight to Monterrey, Mexico; all Russians can easily arrange visas to Mexico online. Next stop: North Carolina. He said he is in contact with other Russians in Nuevo Laredo, Piedras Negras, and Reynosa who all are confused as to whether the new Trump policy of requiring immigrants to apply for asylum in the first country they reach applies to them. None want to apply in Mexico or anywhere but the United States. But it remains unclear how subsequent administration policies like this will impact extra-continental migrants like Vladimir, particularly as court challenges to the policies work their way through American courts.

“I am going to live quietly and calmly in the USA, and I think that this country will allow me to do this.”

Maybe so, when all is said and done. But assuming Vladimir makes it into the United States and finds a way to stay during his asylum claim, whatever his law enforcement problem was, it should be incumbent on U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement intelligence officers in a detention center (presuming they make sure there is room to hold him) to keep him long enough determine whether he is a legitimate victim of police persecution who deserves sanctuary or a counter-intelligence threat on espionage duty, or dangerous criminal fleeing justice in Russia who should be deported instead.

Because the whole system is strained to breaking under Central American arrivals, there’s a good chance Vladimir will quickly be granted legal admission into the United States on a credible fear claim and, eventually, asylum, his potential criminal history and true nature unplumbed.

U.S. Policy of “Metering” Is a Laboratory Opportunity to Learn

Vladimir is among tens of thousands of “extra-continental” migrants who, having seen the ease with which Central Americans were able to flood into the United States, were drawn to try their luck, too. The migrants at Acuña are among an historically unprecedented influx of some 35,000 U.S.-bound “extra-continental” migrants, as I reported in a July 1 blog post, traversing a route from South America and into Panama from places like Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Republic of Congo. From Cameroon and Ghana. And, of course, from as far away as Russia. Plenty of Cubans, Haitians, Brazilians, and Venezuelans are among them.

An issue that so far has escaped analysis is that some of these African nations are home to militias that engage in unspeakable brutalities, extremely violent criminals, Islamic terrorist groups, government persecutors, and murderers on various sides of armed rebellions, economic collapse, and civil wars. Who can forget the 1980 Mariel Boatlift that imported the populations of Fidel Castro’s prisons and mental health facilities into naively welcoming American arms in Florida and beyond, with lasting criminal impact? U.S. homeland security, however taxed right now, will need to set aside whatever they are doing and vet these migrants before they are waved through.

The flow may slow in the near future. Many started their journeys prior to a variety of new American and Mexican bilateral policies designed to deter and manage them. Word of problematic new policies must be getting back to home countries.

The ones in Acuña came face to face with a contested U.S. policy known as “metering”, whereby CBP will take only a few people from Mexican territory each day to establish asylum claims. The policy was originally rolled out under President Barack Obama in 2016 and broadened during the Trump administration as a way to impose some order on the mad dash swamping the system.

Plenty appear to have simply ignored the metering and crossed anyway with some success. For instance, the New York Times reported from San Antonio that hundreds of Congolese showed up at the bus station after their CBP encounters at the border. Earlier this week, 12 Russian immigrants were caught as a smuggler attempted to drive them through the international port of entry at Eagle Pass, Texas, less than an hour from here. But others have abided by the metering system, at least for now.

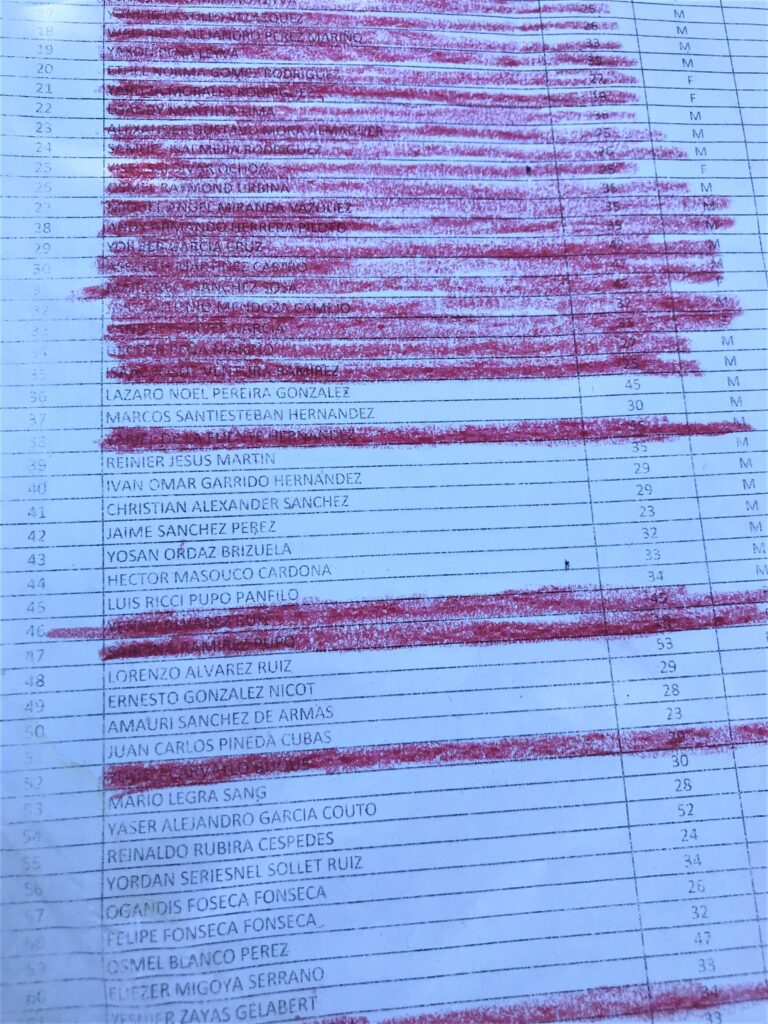

The Center for Immigration Studies was able to interview a representative sample of extra-continentals in Acuña, where they wait for weeks and even months until their names are called from a list, and they are taken across to the nearby Del Rio, Texas, port of entry to lodge an asylum claim with CBP.

CIS questioned some about how they got this far and — importantly, from a rarely examined homeland security standpoint — about their personal involvements with home-country problems. This last factor, country conditions, as I argued in a June 20 blog post, should trigger emphatic American homeland security assessments of some extra-continental migrants.

Allied Countries Aiding and Abetting Extra-Continental Migrants

To be fair, the Acuña camp migrants, far more so than Central Americans whose claims of criminal victimhood and poverty disqualify most for asylum protection, actually arrive with comparatively substantive grounds. They come from lands beset by wars and systematic government persecutions on the basis of ethnic, tribal, and political affiliations.

American homeland security should expect the arrivals of extra-continentals to continue and increase in number, not least because allied governments to our south are not only letting them through but, in some cases, actively participating in their care and transportation, as CIS has reported of Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica.

Reportedly, now the Mexican national guard, which deployed to Mexico’s borders to interdict and return Central Americans, is allowing all non-Spanish speaking migrants through to the U.S. border. In July, a group of eight Brazilian migrants that CBP brought to Deming, N.M., after their uninhibited crossing told town officials (who told CIS) that Mexican national guard units routinely detained Spanish-speakers while letting all extra-continentals like themselves continue on to the U.S. border.

Further south, American authorities are working other angles to slow the flow of Africans. Ecuador, its visa-free policy enabling multitudes of Cameroonians and Congolese to easily reach the Western Hemisphere, very recently expanded the number of countries whose citizens now will need special visas to enter going forward. Eleven countries were added to the list: Angola, Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, India, Iraq, Libya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Syria, and Sri Lanka because of, according to Ecuador’s foreign ministry, “an increase in the number of foreigners entering the country, an increase in those overstaying their 90-day in-country allowance, and an increase of those entering for illicit purposes.”

Still, traffic from the rest of the globe can be expected to find a way around Ecuador. For these reasons, American homeland security, decision-making leaders, and the general public may find the following summations of country conditions useful in in deciding whether to begin conducting pre-release security screenings or to even worry about this traffic.

Atrocities in Cameroon

Warfare between the French-speaking government and the country’s separatist English-speaking population in a western part of the country has driven thousands of refugees into neighboring countries like Nigeria. The U.S.-backed Cameroonian military has been accused of arresting, murdering, torturing, and accosting anyone suspected of working with the anglophone separatists, who are armed and number some 2,000. Militias associated with the anglophone separatists bear names such as The Red Dragons, Tigers, and Ambazonia Defense Forces. Amnesty International has reported that the militants also have committed atrocities on francophone targets.

Several young male migrants of military age that CIS interviewed in Acuña said they and “many” of the Cameroonians in the camp spoke English. Several told CIS they were victims of government military persecution and decided to leave when they heard people could easily cross the U.S. border these days.

Asked whether they or anyone else they knew in the camp had belonged to anglophone militias, all answered “No.”

Hardison Ajone, 30, said he “was caught up in the situation” at one point and was arrested for organizing a large family gathering that government forces interpreted as threatening to security. He said he was beaten and tortured for three days in detention, although his story, like all such stories, could not be verified.

After his release, Ajone said he fled to neighboring Nigeria, where Cameroonian government forces still stalked perceived insurgents.

He and other Cameroonians in the camps there had all heard that a trip to the United States would be successful now and decided to try for it. Everyone was talking about the U.S. southern border. It was all over the news. Two local Nigerians, for $2,500, helped him buy plane tickets to Ecuador, which until recently was a visa-free nation that asked no questions and would allow in anyone who arrived.

Once in Quito, Ajone said he decided, “I can go to America.” Teaming up with other Cameroonians there who all planned to go north, they moved together without a smuggler, learning from social media how and where to travel.

“We moved from one bus terminal to another,” he said, until the group arrived in northeast Colombia. There, they all paid a guide $100 each to get them started on trails through the jungled Darien Gap into Panama. They moved through camps in Panama and Costa Rica crowded with “thousands of people”, many of them Africans.

There was no particular reason to choose Acuña for their crossing; he just followed the herd, so to speak, but was disappointed to find that the Americans and Mexicans would not let them immediately cross. They put their names on the list.

“I’m waiting for my own turn,” he said.

Although nothing in the interviews emerged to indicate deception, U.S. authorities have an obligation to make some effort to determine whether Ajone was persecuted or did any disqualifying persecuting himself. Learning much of anything may be difficult for U.S. authorities, even if the Cameroonian government is asked to report on Ajone’s arrest and activities. But that would be a good place to start, not least because a U.S. relationship exists with Cameroon’s most elite military forces, which the United States helped train and equip to counter incessant attacks by the Islamist extremist group Boko Haram from next door Nigeria.

Democratic Republic of Congo

As I pointed out on June 20, many thousands of murderous, warring militia members have rampaged for years through villages of Central African nations like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) on killing, raping, kidnapping, and looting sprees during decades of ongoing civil warfare. Their atrocities and massacres in the eastern part of that country are the stuff of horror films.

Militia-backed tribalism and warlord-ism aside, just this past April, ISIS claimed its first attack in the DRC, in which eight government soldiers were killed. An ISIS-backed rebel group is murdering thousands, and ISIS itself now refers to the DRC as the “Central Africa Province of the Caliphate”.

The Congo Research Group issued a report in November 2018 documenting the increasing spread of Islamist jihadist ideology among some groups and allied militias, particularly in eastern DRC. Much of this trend seems to have seeding in the Ugandan Allied Democratic Forces, a particularly brutal militia with operations throughout the DRC’s east that is rebranding itself as an ISIS franchise and whose members are now largely composed of converts to Islam. Thousands of violent militia fighters have been sprung in mass prison breaks.

That’s not the worst of it; the CIA World Factbook reports that the DRC is “a source, destination, and possibly a transit country for men, women and children subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking by armed groups and rogue government forces.”

In the Mexico encampment, a number of Congolese migrant men of military age declined to be interviewed or photographed, which does not necessarily indicate a problematic past. One who agreed to be interviewed was Nsilu Watunda Fortunet, a 24-year-old who said he was a university student of engineering and had lived in the capital of Kinshasa. In broken English, he said he was involved in none of the militias or government forces. Fortunet said he actually fled the country’s war three years ago to Angola. He heard about everyone crossing the U.S. border and simply went to the Brazilian embassy in Luanda to obtain a tourist visa.

Once in Brazil, he said he met groups of other Congolese all heading to the U.S. border and just followed along. They traveled on their own by bus to Colombia and then through the Darien Gap with paid guides into Panama. The governments of Panama and Costa Rica then transported the Congolese through to Nicaragua, from which they continued by bus to Mexico and the U.S. border.

American homeland security officers will need to make some attempt to produce assessments as to possible deception over affiliation with violent rebel groups, Islamic terrorists, tribal warlords, and government military units accused of committing atrocities and war crimes. Such assessments can be introduced during asylum merit hearings.

Angola

Although a number of migrants claiming Angolan citizenship were in the Acuña camp, CIS did not have an opportunity to interview them. Like Brazil, Angola is a former colony of Portugal with strong ties by language, culture, and the oil industry. It’s unclear why Angolans are traveling to the U.S. border in larger numbers these days; no warfare or significant civil unrest currently plagues Angola.

But the CIA’s World Factbook entry on the country reports extreme widespread poverty afflicting at least 40 percent of the population, as well as many other social and government competency ills. Most likely, Angolans are economic migrants who also heard that disarray at the U.S. border presented opportunities for an easy approach to through Brazil. Poverty, of course, is not grounds for U.S. asylum.

Cuba, Haiti, and Venezuela

Significant numbers of migrants from Cuba and Haiti have long crossed the U.S. border, most likely also motivated to escape systemic poverty and, in the case of Venezuela, total economic collapse. At issue with these migrants is the challenge of discerning past criminal histories in home countries with governments that either are uncooperative or incapable of providing information.

Interviews with four Cubans at the Acuña camp showed that all were motivated to escape Cuba’s widespread poverty and system of governance. None claimed government persecution, which may form the basis of a successful U.S. asylum claim. Many are coming now because it suddenly became easier, they told CIS, when Cuba and Nicaragua established visa-free airline travel between the two countries.

“You just get the permit and fly in,” said Leosdanys Torres Elorno.

Relatives in the United States pay the airfare and also the considerable government fees required by Cuba for the exit permits.

Elorno and several Cubans nearby said they all took advantage of the visa-free travel as a means to reach the U.S. border, to which they were especially drawn after hearing how easy it has become to cross.

All paid the Cuban government between $850 and $1,300 for “permits” to work in Nicaragua. Elorno said this is an artful cover for what everyone knows “in the back of their minds” is a one-way trip to the United States with no return.

Conclusion

A recent New York Times report about the Congolese said their arrival at America’s southern border “has surprised and puzzled immigration authorities and overwhelmed local officials and nonprofit groups.”

Surprise and puzzlement is not where the Department of Homeland Security needs to be on this traffic.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection must pause from the chaos of the Central American influx and ensure that migrants from global trouble spots are not as quickly released into the interior just to free up bed space in facilities. Instead, bed space should be specially reserved for them so that ICE intelligence, law enforcement agencies, and even the FBI can conduct in-depth security interviews, inspect their pocket trash, take the data from any cell phones, and file detailed reports for the asylum processes to come.