Cossack soldiers in 19th century uniforms, a new “country” called “Transnistria, ” the Russian 14th Army firing artillery its commander swore it didn’t really fire, and Romania-backed government troops. The bizarre history of this former Soviet republic, and the troubled turn at which I briefly found it in June 1992, has contemporary roots in its World War II past, when Nazi Germany conquered the region. Nothing complicated to see here.

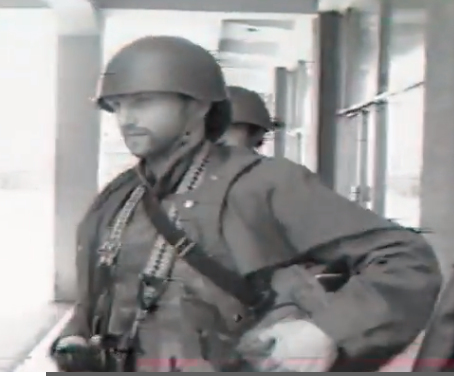

(SEE WAR VIDEO OF BENSMAN HERE) Outtakes from several days on the front lines with two Russian TV journalists (the camera man and a female producer often pictured with me). As we parted ways after three incredibly eventful days together, they presented me with a farewell tape. Based on the Russian separatist side in Tiraspol, we traveled together to the fighting. Quality is poor as the video had aged before I rediscovered the tape two decades later and had it digitized. Scenes include nighttime incoming rockets on our position, various night combat scenes, incoming sniper fire, a daytime patrol through no-man’s land in a factory complex covered by firing enemy snipers, preparations to enter a contested neighborhood, and a visit to a Cossack base behind the lines. In one scene late in the tape, a firefight breaks out along a front-line trench after a sniper round was fired at my group, narrowly missing my head as I sat atop a trench embankment. Soldiers decided to evacuate us from the area in a running dash amid shooting, and I can be seen moving down in the trench behind a soldier).

On Background: News of flaring warfare in the Soviet Republic of Moldova reached me at my base in Prague shortly after I returned from my first successful foray into Croatia, sometime in about June 1992. I was attracted to the story because my freelance mission set at that time was to cover, for a pretty interested American public, the implications of the unraveling Soviet Union anywhere behind the former Iron Curtain.

I first saw the combat video on CNN. I recall talk about major battles between ethnic Russian minorities and other groups in a tiny country I’d never heard of, sandwiched between Ukraine and Romania. I knew I could reach it by train, cheaply. Fighting in other, larger former Soviet Republics was major, well-covered news. So I thought I could market stories about the fighting in this smaller, more obscure – and closer to Prague – story because it was so off the beaten track. I was reasonably sure no other American reporter would bother going there. It had the hallmarks of opportunity.

On a personal level, I was further attracted by how exotic the region seemed. Former Soviet Ukraine… a weird country called Moldova with a rebel capital called Tiraspol… Romania supporting its government in an opposing capital called Chisinau. Too bizarrely interesting to pass up. I wanted to see this land and enjoy the journey both to it, through it, and back. I reasoned that I had combat experience now in Croatia, and I wanted further seasoning for return forays to Bosnia, which was really ramping up then. So I went.

I plotted out my trip – a train from Prague to Kiev first, which required a sleeper accommodation because of the distance. Then, a second train from Kiev south to the Black Sea port city of Odessa. How cool would that be? Then a bus to rebellious Tiraspol and the battlefield. Once in Tiraspol, I’d figure things out as I always did.

The bizarre history of this former Soviet republic, and the troubled turn at which I briefly found it in June 1992, has contemporary roots in its World War II past, when Nazi Germany conquered the region. Its peoples were mostly of Romanian persuasion, speaking Romanian. But Russian-speaking slavs populated a sliver of the east abutting Ukraine. The Soviet army pushed out the Nazis in 1940 and then, after the war, established the Soviet Republic of Moldova. The Soviets nurtured the Russian-speaking east in and around Tiraspol to become a major industrial producer, filled with huge factories churning out about 40 percent of Russia’s needs for mass produced products like cars and heavy equipment. It was a valuable piece of turf. When the Soviet Union broke up in 1990, the Romanian majority wanted an independent country and passed Romanian language laws. They also wanted that highly productive strip of factories in the Russian east. There was even talk of Romania annexing Moldova and of Russia annexing the Russian-speaking east. The stage was set for war.

The proud ethnic Russian speakers weren’t having any of it. Fighting broke out in March 1992 when government soldiers from Chisinau tried to cross bridges over the Dniester River to assert government authority over the factories. With help from the Russian 14th Army stationed there, the ethnic Russians repulsed attempts to cross. There was a ceasefire for a while, then the fighting restarted in June, which is when I first noticed it on CNN and decided to go.

I am no fan of Wikipedia but it’s entry about “the Transnistria War” is well done and credible. It shows the appealing complexity of the conflict that lured me in. Here’re some excerpts:

“The Transnistria war was a limited conflict that broke out at Dubasari between pro-Transnistria forces, including the Transnistrian Republican Guard, militia and Cossack units supported by elements of the Russian 14th Army, and pro-Moldovan forces, including Moldovan troops and police. Fighting intensified on 1 March 1992 and, alternating with ad hoc ceasefires, lasted throughout the spring and early summer of 1992 until a ceasefire was declared on 21 July 1992, which has held.”

The Cossacks. Nothing was more fascinating about this war. After decades of Soviet repression as a threat, the Cossacks – traditionally unltranationalist Czarist Russia border protection guards – had come back to life after the Soviet Union’s breakup. They had dusted off their great grandfathers’ uniforms, donned them, and headed to wherever they saw Russians under siege. According to the excellent Wikipedia entry on this: “The Russian 14th Guards Army in Moldovan territory numbered about 14,000 professional soldiers. The PMR authorities had 9,000 militiamen trained and armed by officers of the 14th Army. The volunteers came from the Russian Federation: a number of Don, Kuban, Orenburg, Sibir and local Transnistrian Black Sea Cossacks joined in to fight alongside the separatists.

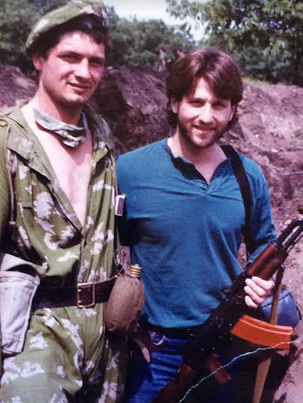

I teamed up with a couple of Russian-speaking Ukrainian video combat journalists for VisNews(male and a female) who were very kind to me, in that they let me travel with them, on their company’s dime, all over the battlefield for nearly a week. Here are photos I took of the Cossacks at one of their main bases we visited in Tiraspol:

We saw combat when we traveled out to their part of the front line. All was very quiet at the front, with scenes very reminiscent of World War I footage. Until a sniper’s bullet nearly took off my head. This started a furious gun battle between my Cossack hosts and the other side about 150 yards away. After escorting us down the trench for 100 yards, the three of us zig-zag sprinted to our car and driver, who sped away with us out of the war zone.

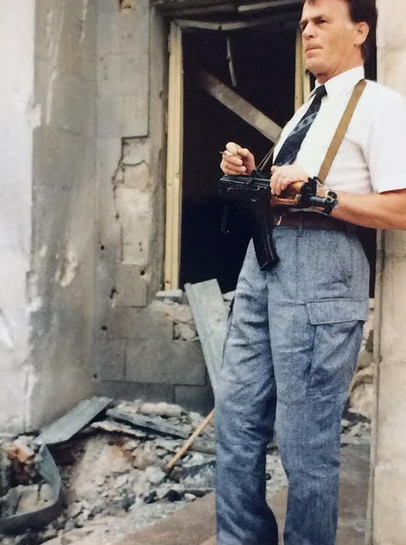

Somewhere in there, we went on patrol into a disputed factory district. It was still a no-man’s land, and our escorts were highly tense. I recall many shots being fired during this insane patrol, and a lot of running and dodging to get into a textile factory that had recently been bombed. Later, some mortar rounds or something went off. We found the spot where an artillery round had hit and shattered windshields of every vehicle in site, leaving a still-smoldering hole. The patrol:

More from the unusually excellent Wikipedia article regarding the Russian 14th Army, which I saw use the artillery that night described in the article:

“Although the Russian army officially took the position of neutrality and non-involvement, many of its officers were sympathetic towards the fledgling Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) and some even defected in order to help the PMR side openly. On 23 June, in the wake of a coordinated offensive by Moldovan forces, General Major Alexander Lebed arrived at the 14th Army headquarters with standing orders to inspect the army, prevent the theft of armaments from its depots, stop the ongoing conflict with any means available and ensure the unimpeded evacuation of armaments and Army personnel from Moldovan and through Ukrainian territory. After briefly assessing the situation, he assumed command of the army, and ordered his troops to enter the conflict directly. On 3 July at 03:00, a massive artillery strike from 14th Army formations stationed on left bank of the Dniester obliterated the Moldovan force concentrated in Gerbovetskii forest, near Bendery, effectively ending the military phase of the conflict.”

The guns referenced were right behind my hotel. I was there that night when the barrage started. In fact, I left the hotel and drove over with some other reporters in the hotel to watch the action up close, right on base with the artillery.

The next morning, at a press conference with General Lebed, he completely denied firing the guns, saying the 14th Army was neutral. Completely hilarious.

I was having trouble filing my stories because all communications from Transnestria had been severed. I tried sending stories out with other journalists, but nothing ever made it out. But this was a hell of an experience that I will never forget.