Stories, photos

Includes never-published photos

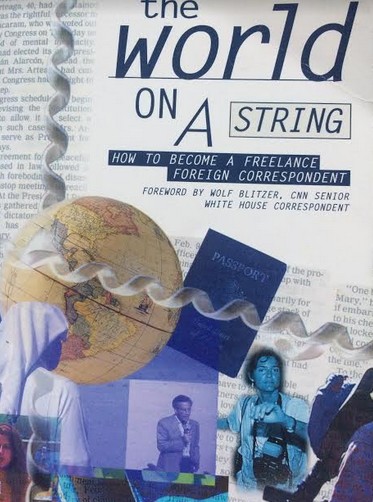

On background: Long after I returned to the U.S. and took a staff writer’s job at The Dallas Morning News, a call came from the author of a forthcoming book titled, “The World on a String.” It was to be filled with useful advice for aspiring freelance reporters about how to succeed abroad. The authors told me they had heard from a mutual friend that my first try, covering the Gulf War, hadn’t gone so well. They wanted me to recount what went wrong, as well as to describe how I later used those mistakes to turn things around. The book did a pretty good job of describing the experience, so I’ll let excerpts set things up:

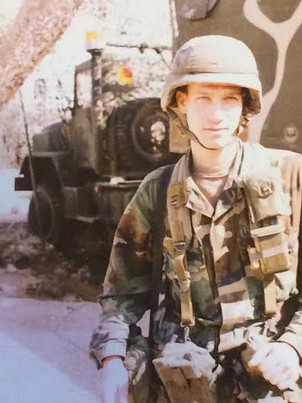

“Consider a third example. Todd Bensman, who would later freelance very successfully from Eastern Europe, made snap decision to quit his job at The Anchorage Times,

“So when the United States started bombing Baghdad, Bensman gave notice at work. He cashed in his savings – $4,000 in Certificates of Deposit—bought a cheap laptop, and got a ticket to Tel Aviv. He picked Israel largely because

“When he stepped off the

plane, security officials immediately issued him and the other passengers, mostly

Israelis, gas masks and antidote injection kits for emergency use should a SCUD

hit with poison gas. ‘I was psyched, and probably a little bit naïve about the

danger,’ Bensman recalled. It was his first trip outside the United States.

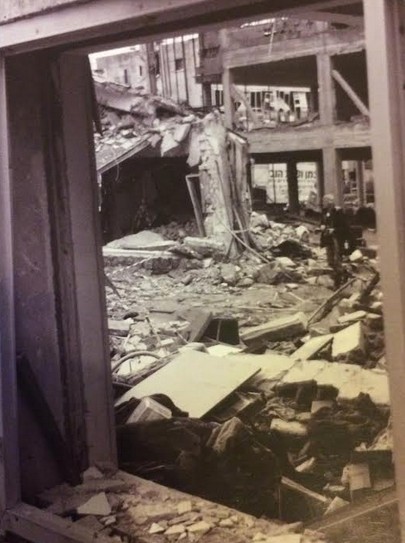

“Bensman found a trickle of work relatively quickly, collecting man-on-the-street quotes for United Press International after each SCUD attack. Staying at a chintzy hotel north of Tel Aviv, he’d take the bus each day to the Hilton, where many of the staff correspondents were based. As the sirens wailed, the reporters would wait on the lawn, listening and watching for the falling missiles, the nearest of which hit about a half-mile away. Then, according to Bensman, they would “pile out like ants from a kicked anthill, running for the cabs.” The cabbies, it seemed, always knew exactly where the missiles had hit and the fastest way to get there. Bensman arrived with the rest amidst the smoke, flames, screaming, and soldiers, even snapping a photo (which he couldn’t sell) of a SCUD’s nose cone that had crashed into the front seat of a Chevy Nova.

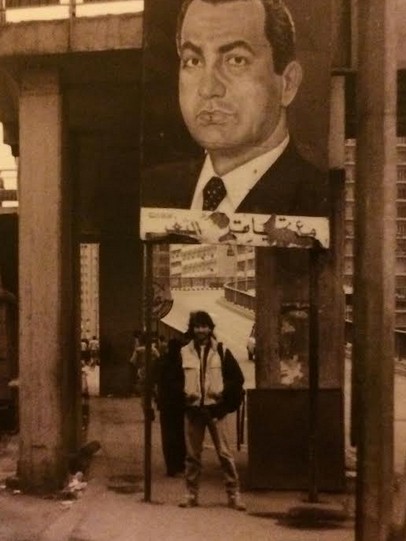

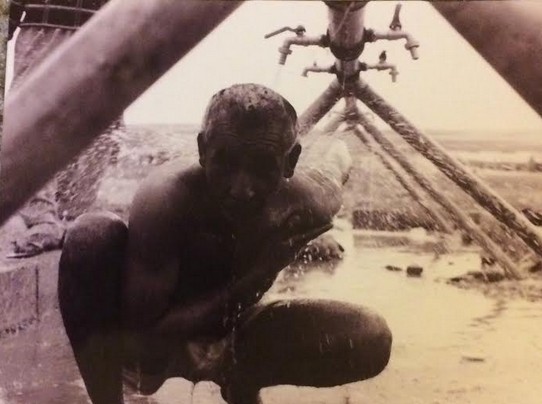

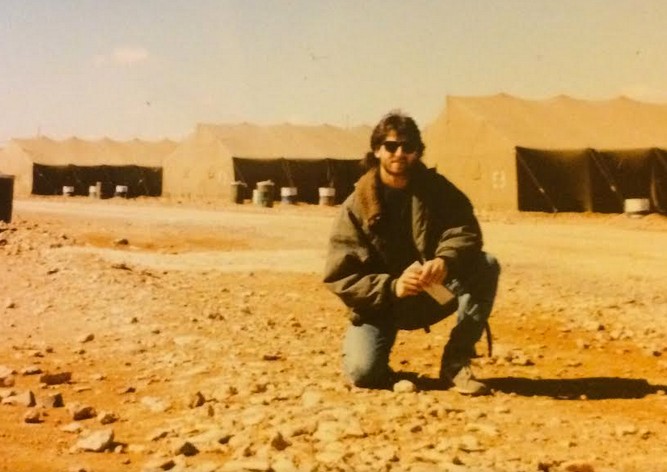

Tel Aviv during SCUD missile attacks and working one of the attacks (below). Photos by Todd Bensman

“The only problem was that each taxi ride cost about $30, and he was getting paid $20 for each file he phoned in to the UPI bureau chief in Jerusalem. With hotel bills, food, and phone calls, Bensman was going broke quickly. In two weeks, he had spent nearly a third of his money. Bensman knew he needed to generate some cash flow, and fast. So between attacks, he networked with staff correspondents and worked the phones, trying to pitch stories to distant editors. It became an exercise in frustration.

“I was talking with an Australian news agency editor, chatting it up, and thought I was making progress. Then, while I was on the phone, there was a missile attack. ’“Hey, there’s a missile attack! Do you want something?’

In what was becoming a very humbling and expensive lesson, Bensman realized that, in the grand scheme of Middle East coverage, he didn’t count. For the most part, the only time his copy regularly made into print was when it spooled off the fax machines of uninterested editors.

The mistake was believing that just by being there I would be a marketable commodity. There was a glut. I was a nobody.’ In short, Bensman had chosen his region poorly. And things were only going to get worse.

“Virtually shut out in Tel Aviv, Bensman realized after two weeks that he had to compete in a less crowded arena or go home. So he headed for Jordan, with unrealistic hopes of getting an Iraqi visa there and proceeding to Baghdad. Spending a precious $80, he hired a taxi to Amman and crossed the famed Allenby Bridge. The road to the capital was dusty and crowded

“The war looked like it was getting closer. The taxi dropped him at a dingy downtown hotel – bugs crawling over the dirty carpet, wooden beds with thin mattresses, and no hot water, but only $7 per night. It’s main asset? A fax machine. He was the only guest.

“Not surprisingly, major media had beaten him to Amman, too. He worked the Inter- Continental Hotel for contacts, knocking on the doors of every western journalist staying there. ‘I would go into people’s rooms, give them my spiel and basically beg,’ Bensman recalled. But they had no work to offer, and he was still having a tough time selling story ideas over the phone to unfamiliar editors.

Meanwhile, the meter was running. Bensman’s savings were quickly disappearing. Apart from his hotel, everything was expensive. “It was an economy set by the networks,” he said. Jordanians assumed that ‘if you were a foreign correspondent, you were a bottomless pit of money.’ Bumming rides from Japanese TV crews and filing

On Background again: From Amman, I was able to do a few stories, as follow, about anti-American protests and refugee camps on the Iraqi border that, for various reasons and again to my chagrin, never filled. In the end, I left the country hoping to take a ferry to the Egyptian Sinai and then by bus to Cairo; the ship turned out to be packed to overloaded with Egyptian refugees fleeing Iraq. I took the horrendous journey with the refugees and later penned a story for UPI that, I was gratified to be able to personally see, ran in all the Egyptian papers. After the war, I returned to Israel for awhile to try to cover the Arab “Intifada” for cash-poor UPI in exchange for office space and use of the phones and fax facilities. But, as recounted in World on a String, luck just wasn’t with me that trip:

“Todd Bensman, who after the Gulf War volunteered in UPI’s Jerusalem bureau in exchange for office space, almost parlayed his experience and the goodwill he generated into a job with UPI, covering the Kurds in Turkey. In the end, though, somebody else got the job and Bensman went broke. He decided to fly back to Alaska, where he lived out of his rusting pickup truck and gutted fish in a salmon cannery for several months until he could save enough money to drive down to the lower forty-eight, marshal his resources, and relaunch himself abroad, this time with solid preparation.”

Amman mosques brand U.S. ‘infidels’ in calls for prayer over loudspeakers

By Todd Bensman

Special to The Anchorage Times

AMMAN, Jordan – Mosque and church loudspeakers called people to special prayer Sunday morning following news of the allied ground

Amman’s Roman Orthodox Church told parishioners to pray for an end to the war and all world problems, while most Islamic mosques publicly changed prayers calling on Iraq to defeat “the infidels.”

Anger and apprehension were perceptible in the streets. A Spanish television crew was beaten in central Amman as it tried to conduct interviews, and Western journalists were advised to stay

“I think people are very, very angry, but they want to know what’s going on,” said Abdullah Hassanat, assistant editor of the Jordan Times. “If you get lots of Iraqi blood, you can expect some anger to spill out into the streets, but if Iraq is winning, people will get jubilant. The people here basically want to bloody the nose of the United States and its allies.”

Jordan’s King Hussein had not addressed the nation as of Sunday evening. But in a morning address, Jordanian Prime Minister MudarBadran condemned the invasion and called for an immediate cease-fire.

Information Minister Ibrahim Izzedin said in his regular morning news briefing that Jordan was surprised by the invasion but did not anticipate serious trouble in the streets. Instead, he said, a prolonged period of suspicion, tension and bad feeling had begun.

The U.S. Embassy in Jordan was open Sunday. The embassy last month reduced its 132-member staff to a skeleton crew and has been the scene of several raucous anti-American demonstrations.

Embassy officials said Sunday they had ordered no special precautions. The usual contingent of three Jordanian guards and a mobile machine gun emplacement were evident, but an additional army truck loaded with riot troops stood parked nearby.

Jordanian residents, meanwhile, were observed throughout the city listening to radios for additional news. Many expressed outrage at news of the invasion.

“Bush? I want to kill because he kills the Arabs,” said taxi driver Fadal Al-Sogayer. “I hope Iraq kills the American soldiers and Egypt, Syria, and France.”

Others expressed joy at finally seeing an opportunity to destroy the allies.

One Iraqi in Amman on business predicted his country would “crush America.”

Egyptian refugees endure grueling 40-hour return home

ByTodd Bensman

UnitedPress International

CAIRO, Egypt – Thousands of Egyptian refugees who fled war-ravaged Iraq and Kuwait are pouring into the Jordanian port city of Aqaba, where they squeeze onto a ferry and endure a 40-hour trip home with virtually no food or sleep.

Until the Gulf conflict, Aqaba had been a posh international playground for the rich and was Jordan’s only shipping point. Now, it is inundated with Egyptian refugees, who until recently were held at the Iraq border by obstinate Iraqi immigration authorities.

Iraq eventually opened its border with Jordan in the final days of the war. However, getting out of Iraq is proving to be the easiest step in an exceedingly arduous journey for thousands of Egyptians.

More than 2,500 men, women and children, and everything they could carry when they left Iraq, were carried aboard the 1,800-seat ferry called the Sarah. They waited in long snaking lines for hours in the hot sun before they could board.

A reporter who made the three-hour boat ride with the refugees from Aqaba across the U.S.-blockaded Red Sea to the Egyptian Port of Newefah, and then by bus to Cairo, watched as the refugees crowded the ship’s stale interior and violently undulating shoulder-to-shoulder throngs.

During the lengthy boarding, scuffles broke out between heads of families over precious strips of floor space. There were violent hallway pushing matches in which hundreds participated. Frustrated ship crew members screamed their throats raw.

Mountainous heaps of luggage formed in the ship’s hold, thrown there haphazardly and with no particular reclamation procedure in mind.

Every private cabin on the ship was stuffed with personal belongings trucked in from the dock. It was another four hours before the Sara departed.

“We’ve had 500 to 700 people a day before they opened the border, and since then it’s been more than 2,000 three times a day. We have no choice but to put them all in like this,” said Mohmud Adhaleem,

Because so many Egyptians displaced by the war are coming to Aqaba, and the airlines have not yet resumed service to Jordan, Adhaleem said, the Egyptian government has drafted two more vessels to relieve overcrowding. In another month or so, they will be needed again to ferry Egyptians who want to return to Kuwait or Iraq, he said.

Food was available at the ship’s cafeteria, but only to those who fought their way down from another deck, waited up to an hour in a line to get a coupon and then even longer on a second line for a single helping of beans, chunks of beef and bread.

Most carried aboard some food of their own,

depositing their refuse nearby.

“I can’t believe how terrible this is,” said Abdallah Ahmed, a 23-year-old former restaurant worker trying to sleep on a crossed outside deck beside a busy stream of foot traffic. “I did not sleep for two days.”

Once the Sara docked at the Egyptian port, a weary cheer went up, but it would be yet another three hours before most of the passengers could begin to disembark. Fifteen buses shuttled the exhausted evacuees to detention areas where they were held for

Port police prevented them from leaving and refused to explain the delay. A bag of bread was distributed at one of the centers, but several weeping mothers cradling infant children complained of having no more milk. Dozens of people

But the worst was yet to come. Baggage claim for thousands was to last more than 10 hours. Trucks and tractors pulled loads from the ship into a roughly 5-acre concrete staging area and dumped amid thousands of scrambling Egyptians trying to identify their belongings. Each new truckload was mobbed by pushing, shouting people, many of whom would return empty handed to a makeshift camp on the dirty ground in the compound to await the next load.

More than 30 hours after arriving, about 2,000 Egyptians still had not claimed all of their belongings, and hundreds more waited in long, slow-moving customs lines in a building nearby. An eight-hour bus trip still lay ahead.

Tanseur Qutob, a 25-year-old traveler utterly spent after the journey, said, “I wish I was not here. Nobody can imagine what it was like. I was a very sad guy. I wish it had not had to happen to me.”