A four-part series from an undeclared war

With powerful warring drug trafficking organizations and Mexico’s military laying siege to one another by 2009, a growing number of citizens saw only one way to survive: by fleeing over the American border. They have arrived with gruesome stories of kidnap, torture, extortion and random brutality at the hands of ruthless trafficking groups. The arrival of these refugees was a new phenomenon, born of a civil drug war that had claimed 10,000 Mexican lives since 2006. In other parts of the world, wars pushed thousands of terrified refugees into neighboring countries. Reporter Todd Bensman set out to document this largely under-scrutinized population of fleeing drug war

PART I: US-backed covert op brings cartel vengeance on two brothers

NUEVO LAREDO, Mexico — All is quiet now on Coahuila Street. But traces of the violence that destroyed the lives of two American brothers with businesses here linger.

A blackened structure is all that’s left of Alan Gamboa’s once-profitable radio communications business, after it was drenched in diesel and burned to the ground the night of Dec. 5. His brother, Ricardo Gamboa, is still missing— and feared dead — after being kidnapped by cartel gangsters on Coahuila Street the previous morning.

Violence and kidnappings have become almost commonplace in Mexico, as the country’s civil drug war rages. Often, the murder and kidnap victims are American residents of border cities like Laredo, who are involved in the drug trade.

But the violence that upended the Gamboa brothers’ lives is different. By all accounts, they were not drug dealers. Their only transgression, it seems, was to rent a house to the U.S. State Department and Drug Enforcement Administration, which set up an anti-cartel intelligence operation with Mexican federal police in the rented space.

The brothers’ tragic story offers a rare glimpse into a part of Mexico’s drug war that gets little notice. The narrative of the conflict as a fight to the death between drug cartels and the Mexican government often excludes another player: the U.S. government. And as the Gamboa tale demonstrates, the American government’s actions in Mexico can also lead to casualties.

Alan Gamboa blames all that has transpired — and what might yet — on his government. He believes the U.S. thoughtlessly placed the brothers in the cartel’s cross-hairs after they had spent years trying to walk a neutral line in violent times.

“It’s not fair! It’s not fair! It’s not fair!” Gamboa lamented. “They (the DEA) put us into a very deep problem, very deep. They (the cartel) think I’m an informant, but I want them to understand that I don’t do that. If I knew that house was for an intelligence organization, I would never have rented it out. I never wanted any problems.”

For now, Gamboa feels he has no choice but to lay low with his wife and three children (ages 9 to 16) across the river in Laredo, Texas. Both brothers lived with their families on the U.S. side while running communications businesses on Coahuila Street across the river in Mexico.

“The cartel wants me dead,” Gamboa said.

In an interview in their Laredo home, Gamboa’s wife, Elsa, said, “What they’ll do is let you settle into your ways, and that’s when they’ll hit.”

DANGEROUS TENANTS

The Gamboa family’s travails began early last year when Alan leased the house directly across from his business to the U.S. consulate, whose officials led him to believe it was for some new low-level employees.

A number of witnesses in Nuevo Laredo confirmed his story. Gamboa said he was led to believe the men were merely low-ranking consulate workers in need of a place to live. Ricardo Gamboa had no involvement in the transaction at all — in fact, the brothers had been estranged for years over past business disputes.

The realtor who handled the deal (who declined to be identified for security reasons) said in an interview that he sent the contract by courier to the American consulate, where it was signed and returned by courier with eight months advance rent. Several Mexican men then moved

American officials acknowledge the house was used as a “forward operating base” from which their Mexican counterparts were hunting cartel members, with DEA money, intelligence and other support.

The Nuevo Laredo operation was emblematic of countrywide U.S. law enforcement efforts to help Mexican President Felipe Calderon’s government in the war against that nation’s heavily armed drug trafficking organizations. Nuevo Laredo is one of the border’s busiest trading corridors, making it one of the most fought-over trafficking routes.

But as the Gamboa brothers would soon learn, the U.S. and Mexican governments aren’t the only ones with intelligence operations. The trafficking organization that currently controls Nuevo Laredo, called the Gulf Cartel, has a sophisticated counter-intelligence network of its own.

A State Department official based in Mexico and a senior U.S. law enforcement official, who requested anonymity for personal security, confirmed that the U.S. government paid to rent the house for a Mexican intelligence operation. But they sought to deflect blame for the Gamboa family’s troubles, saying that the motives for moves against the brothers are unclear.

“It’s terrible when even one person is killed or kidnapped,” the state department official said. “But we’re talking thousands murdered. Understand that if, working with our Mexican counterparts, we don’t get smarter and stronger, it could get worse rather than better — that there’s really no choice” but to continue fighting the traffickers.

But the DEA and Mexican federal police may have a more pressing problem from the episode: cartel gunmen seized all of the computers and file cabinets related to the operation, raising the specter of an intelligence breach that may have put agents and informants at risk on both sides of the border.

Shattered peace

Although American citizens, the Gamboa brothers lived most of their lives in Nuevo Laredo, building separate but similar communications businesses over twenty years down the same street from one another. As retailers of radio and cell phones, repeater towers and security surveillance systems, they had come to know how to navigate a neutral line between American and cartel clients alike.

Married fathers of young children, the Gamboas moved with their families to the U.S. side of the river three years ago to escape cartel violence wracking Nuevo Laredo.

The move left the house on Coahuila Street vacant.

Oct. 1, 2008, the violence began.

Former Mexican army special forces officers, who now work as cartel enforcers (known as Zetas), somehow captured one of the Mexican undercover agents living in the Gamboa house, American officials confirmed. Thirty gunmen — clad in mismatched camouflage uniforms —took part in a dramatic daylight raid on the house, according to eyewitnesses. The gunmen blocked off both ends of Coahuila Street while an SUV was used to batter down a garage door.

The gunmen smashed into the courtyard and house, breaking surveillance cameras and carting off desktop computers, as well as laptops and boxes of documents. The abducted agent, who was forced to attend the raid, was murdered later that day.

A ranking American law enforcement official with direct knowledge of the operation, who requested anonymity for personal security, said it was difficult to determine how damaging the breach was.

“We do not believe that any information about the DEA investigation was on those computers or in the materials,” the law enforcement official said.“We do not believe that anything was compromised that would enhance the risk beyond what we already have. However, we can’t say what the federal police had put on that computer or what. We just don’t know.”

Requests to the Mexican attorney general’s office for comment about the seized computers and documents went unanswered.

For two months after the raid, there was relative calm. Then, the cartel struck the Gamboa brothers, apparently in the belief that they were collaborators.

The morning of Dec. 4 was the last time anyone saw Ricardo Gamboa — he was climbing into a gold SUV in front of his office.

Alan Gamboa said he was lucky to have been in Texas the next day when gunmen ransacked his business, stealing radio equipment, records

Given that the Gamboa brothers’ estrangement from one another was widely known, both families are wondering why Ricardo was taken when it was Alan who rented the house.

Collateral damage

Veronica Gamboa, Ricardo’s wife of 13 years, sat in her dining room table one recent afternoon inside the couple’s Laredo home. Photos of the couple’s two young daughters, 11 and 8, who adored their father – and vice versa – are displayed on a nearby table.

A yellow ribbon was tied around a wrist, a large yellow bow set above the front door. Tears streamed down her face as Veronica recalled how she became aware that Ricardo was gone.

She’d been with him that morning at the office in Nuevo Laredo. Ricardo said someone was about to pick him up and take him somewhere to give an estimate for a security system.

She went into a back room and that was the last time she saw him. It wasn’t until a presentation of the Nutcracker the next night in which their daughters were performing that Veronica knew for certain Ricardo had fallen victim to foul play.

“He….” Veronica struggled to explain through her tears. “would never …have missed that. Not that.”

Now her days revolve around phone conversations with an FBI case agent. The FBI is responsible for investigating kidnappings of American citizens on foreign soil. The family also works its own friends and contacts in Nuevo Laredo, trolling for any word about Ricardo’s whereabouts.

Often in kidnapping cases, a ransom demand is extended. The absence ofanything like that has Veronica fearing the worst. FBI officials would not discuss the case in detail other than to say agents are working it as an active kidnapping case.

Still, until last week, Veronica was holding out hope that the cartel had put Ricardo to work setting up communications systems somewhere,

“Ricardo’s a very, very intelligent man,” she said.

But last week, bad news came from both the FBI and family sources. It was that Ricardo will never be coming home because he was murdered.

No one has reported seeing a body. Like everything else the family’s heard, the information is unsubstantiated and still amounts to rumor. So without proof, the family still holds out hope that Ricardo will return to his daughters.

Staff photographer Jerry Lara contributed to this report

Part II: A Mexican lawyer in hiding from his drug lord boss

MATAMOROS, Mexico — Blindfolded and bound, Ernesto Gutierrez Martinez felt the guards guide him from his cell to an outdoor area.

He caught a whiff of fuel and heard a man crying. The armed men at his sides, who so often had beaten him unconscious, were laughing with sadistic glee.

“This is how we prepare a soup,” one of them quipped.

His blindfold torn away, Gutierrez saw he was in a small courtyard. Another bound prisoner of the Gulf cartel stood in a metal barrel, blubbering prayers. Someone was spraying him with a flammable liquid. Someone else flicked a lighter.

Gutierrez’s own scream of horror could not escape the rag stuffed in his mouth. He thrust his head to one side to avert the sight of the screaming mass of flesh and stench. The guard grabbed a fistful of Gutierrez’s hair and yanked his head back up. He was next, they kept saying.

Later, back in his cell awaiting his fate, some of the same tormentors started up a friendly banter.

The killers wondered why Gutierrez — an urbane, well-to-do attorney — had come to be a prisoner in this house of torture and murder.

“They said I was not the type of person they normally have there,” he recalled. “They were asking me why I was there. That I must have done something very bad.”

Gutierrez said nothing but knew it had to do with his role as family lawyer for Osiel Cardenas-Guillen, boss of the Gulf cartel.

One day, as abruptly as they grabbed him from his law office, his tormentors let Gutierrez go with a demand that he do legal work for the cartel.

Three weeks of beatings and no food left him emaciated and infected from wounds, but Gutierrez knew what he had to do. He ran for his life.

Not just any lawyer

Now, 21 months later, Gutierrez and his family are hiding in the United States, still feeling hunted and prepared to bolt at any inkling of discovery. The sleeves of his shirt barely cover the handcuff scars on his wrists — a reminder that if the cartel’s Los Zetas paramilitary enforcers find him, he won’t go free a second time.

While returning to Mexico is risky, staying in America is perilous in another way. Gutierrez is making a long-shot attempt to gain political asylum in the U.S., joining a growing number of Mexican refugees — police officers, journalists and businessmen — in need of protection from cartel persecution.

But the U.S. government is opposing many asylum requests because, experts say, the law doesn’t squarely apply to victims of Mexican organized crime. Immigration judges, for various reasons, have sent some of them back.

For Gutierrez, the dread of falling back into cartel clutches has prompted him to abandon or sell everything: the law practice that supported his family, two homes in Mexico, a $210,000 house in Brownsville, a South Padre Island condo, sports cars.

He also left beloved extended family members whom he can’t contact for fear the cartel will torture them and find out where he is.

“The government is fighting these cases like crazy, any excuse to deny these claims,” said Eduardo Beckett, managing attorney of the Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso, which has lost a number of the cases but doesn’t represent the Gutierrez family. “They don’t want to open up the floodgates.”

For example, last year only 71 out of several thousand Mexican asylum seekers were accepted.

Gutierrez may face an added hurdle because of his notorious client.

As head of the Gulf cartel, Cardenas was Mexico’s most wanted fugitive and one of America’s when Mexican troops captured him in a 2003 Matamoros shootout.

After the capture, Gutierrez worked for four years with the legal team that failed to block Cardenas’ January extradition to Houston in January 2007

In considering asylum, the government will want to know whether Gutierrez ever strayed into criminal activity for Cardenas — and got burned for playing with fire — as have other Mexican attorneys.

Gutierrez insists he was made to pay, in pain and blood, only for the lost extradition battle.

That extradition cost Cardenas his continued power over the cartel. It set up Cardenas for a trial this September in Houston on some two-dozen organized crime charges that could put him away for life in a U.S. prison. And, it ended any hope that Cardenas might buy an escape like the one last month when 53 cartel gangsters walked out of a Mexican prison.

Through his Houston defense lawyers, Cardenas denies having anything to do with Gutierrez’s abduction, or the bad luck of some of his other attorneys in Mexico. At least three who worked for Cardenas ended up dead, full of bullets.

“Mr. Cardenas never ordered, directed, nor even implied that the Zetas kidnap or harm Mr. Gutierrez,” said Chip Lewis, who is part of the Cardenas defense team. “He had no problems with Mr. Gutierrez. Whatever the Zetas did or did not do was not at his direction.”

Sucked in

Gutierrez agreed to share his story and asylum petition files, which aren’t public, with the San Antonio Express-News in hopes that independent scrutiny of his claims might aid his chancy asylum bid.

He spoke only on condition that details indicating his family’s whereabouts not be disclosed. He only would agree to meet in public places. He requested that no photographs of him be published in case a cartel operative recognizes him.

Gutierrez lives in an anxious, stateless limbo, burning through his savings from the sale of properties. He won’t go near any part of his old life, even on the U.S. side, in the belief that “they” are watching.

“In Mexico, there’s no hiding,” he said in Spanish “There’s no safe place. I can’t

Gutierrez traces all of his troubles to Jan. 29, 2004. That was the day Celia Salinas Aguilar de Cardenas, wife of Osiel Cardenas, walked into his law offices. The government had seized her house, she said. Would Gutierrez help her get it back?

By then, the 1985 University of Tamaulipas law school graduate didn’t need the money. Hailing from a family of Matamoros lawyers and doctors, he’d already built a prosperous civil practice of contract law, divorce and —significantly — cases involving government property seizures.

Gutierrez insists he’d never handled criminal defense cases nor worked for anyone involved with the cartels. Still, he admits he was a bit intrigued by such an infamous client.

The Zetas had a fearsome reputation of not taking no for an answer, but in the end, Gutierrez rationalized: “Everyone knew me in Matamoros; I wasn’t scared.”

Those sentiments would change as the Cardenas family pulled him in deeper.

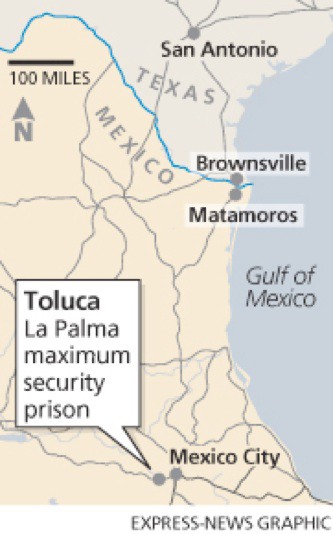

First, Celia’s sister came to him with a house seizure case, followed by Osiel Cardenas’ father, who also had one, Gutierrez’s law files show. Then, in February 2004, Cardenas summoned him to La Palma prison in Toluca to discuss the property cases.

Cardenas asked Gutierrez to join a team of 20 other lawyers gearing up to fight a U.S. extradition effort.

Gutierrez wasn’t enthused by the nine-hour drive to Toluca and time away from family. But mindful of the potential cost of saying no, he said he agreed to only a part-time advisory role. This required twice-monthly visits with Cardenas and some special projects for the team.

The deaths of some of his teammates demolished any pretense that his prominence offered immunity from such a fate.

In January and March 2005, the bodies of two Cardenas lawyers that Gutierrez knew were found riddled with bullets not far from La Palma prison gates.

Leonardo Oceguera, one of Cardenas’ lawyers just before

and after cartel assassins murdered him in Toluca. AP

The assassinations were reminiscent of a 2002 attack by soldiers on a carload of Cardenas lawyers in front of the prison that left one of the attorneys dead after a chase.

“I was scared, I didn’t want to go anymore, but after what happened, what can you do? Not go?” Gutierrez said.

Pressed in interviews with the Express-News, Gutierrez distanced himself from Mexican news accounts implicating other lawyers with helping Cardenas run the Gulf cartel from Toluca.

They allegedly acted as messengers, paymasters

The Mexican government even sent troops and tanks to La Palma in 2005 to stop what it said was a helicopter escape plot possibly aided by the attorneys. All of Cardenas’ lawyers were banned from the prison for a time.

Involvement could end Gutierrez’s political asylum dreams

Gutierrez insists he was an outsider based in distant Matamoros who never strayed from legal work and had little contact with the Toluca team or its alleged maneuvers.

“There were some lawyers doing that,” he said after a long pause. “But I was never present when they would talk to Osiel. When I would go, we would only talk about that case. There was no trust to talk about anything else.”

Chip Lewis, counsel for Cardenas, confirmed Gutierrez’s depiction of himself as having played a bit role with the Toluca team.

“He was not involved in any of the major decisions regarding any of the criminal matters or the extradition.”

The price of losing

Two days before an aircraft flew him to Houston, an unusually agitated Cardenas summoned Gutierrez for

“I had never seen him like that. His eyes were weird. You could see anger in his face,” Gutierrez recalled.

Cardenas queried him — hard — about a missed deadline to file a motion. He said the lawyers had “screwed up.” Gutierrez said he reminded Cardenas of his distant advisory role. Gutierrez wished Cardenas well and went home to rebuild his neglected practice.

A week later, several Zetas barged into his office carrying a Nextel radiophone. On it, they said, was acting cartel chief Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sanchez. The voice warned the cartel was investigating legal mistakes. Gutierrez would be killed if faulted.

Five months later, at about 3 p.m. Aug. 17, 2007, a team of 10 armed Zetas stormed his second-floor office, according to an affidavit from a client who was there. The men hammered Gutierrez with gun butts to the face and head, starting streams of blood. They handcuffed, blindfolded him, then hauled him outside to a waiting vehicle.

Some 20 minutes later, the vehicle stopped at what Gutierrez guessed was a detention center. He could tell by the screams and the sounds of beatings, which he would hear from his 6-by-6-foot room day and night.

Too often, he would hear someone scream, “‘Oh my God,’ and then you could hear a shot fired and nothing else.”

Over the next three weeks, he ate nothing. He was not allowed to use the bathroom. He was beaten most days, often to unconsciousness, by a baseball bat, iron bar, fists

Pictures taken later show a festering infection on his broken nose. A medical report notes a right eye socket partly collapsed and eye damage. The handcuffs never came off, digging deep into his skin and causing an oozing i

But the psychological abuse was far worse. Constant threats that his turn to die had arrived were underscored by murders he was forced to witness.

In addition to the prisoner burned to death, he said he was forced to watch as another prisoner was shot through the head. Morticians were called in to clean up the messes.

On another day, they brought him out to see a man’s throat cut so deeply the head almost toppled off. Gutierrez was splattered by blood. The Zetas then put a knife to Gutierrez’s throat and cut, though not quite deeply enough to kill. They told him they’d instead concoct an especially creative way to torture him to death. A thin scar runs horizontally across his two jugulars.

Once, the guards sprayed him with a flammable liquid, saying they had finally gotten around to burning him alive.

Then, inexplicably, one day the Zetas said “el jefe,” the boss, had ordered him treated, cleaned up and released.

A Nextel phone was placed at his ear on the drive to his waiting car. Again, a man identified as Cardenas’ top deputy, Costilla, told Gutierrez he was needed to represent a forthcoming list of jailed cartel gangsters.

He credits his survival to his victories on the Cardenas land cases.

“I think they needed me. I won many cases for them,” he said.

Gutierrez agreed at once, of course, but privately vowed he never would waste this unexpected gift.

Flight to America

He drove straight to the home of his sister, an emergency room doctor, and her surgeon husband.

She recalled answering the doorbell at 2 a.m. to find the dreadful but wonderful sight of her emaciated, bleeding brother. She began treating his wounds.

“We thought he was dead,” she said. “I know from my work at the hospital that a lot of people go through this and end up dead. But he was here. He was here! We have him.”

After a tearful reunion with his wife, Josephina, and the children later, the couple realized the danger they were in. It was decided that Gutierrez would go to Brownsville the next morning. Josephina would stage a more orderly retreat to join him a week or two later.

Two days later, Zetas showed up at the couple’s Matamoros home, demanding Gutierrez.

Josephina, hiding her youngest in a back bedroom, swore he was at the doctor’s office. They threatened to kill her and the children if he didn’t show up at his office to receive his legal assignments. After they’d gone, she grabbed toys and clothing, piled the kids into the car and fled to Brownsville.

Fear followed the family members, though. They knew they’d committed the unpardonable sin of defying direct cartel orders. It didn’t help that one of Cardenas’ daughters lived in a Brownsville mansion a block away. The couple turned their house into a bunker of steel storm shutters and a sophisticated surveillance camera system, never turning on an outdoor light after dark. They emerged only for food and school.

The Express-News confirmed a neighbor noticed young men cruising the street in brand new SUVs, pausing at the house. One day, he told the couple about a driver taking photographs. The same week, Gutierrez’s father told the Express-News, a cartel operative contacted him with a warning: Gutierrez had to turn himself in or face abduction and worse.

Overnight, the family fled north. The house, with its odd shutters, is for sale. Records show the Gutierrez family members also sold a vacant lot they owned in town. They said they are living on the proceeds.

Every door and window covered by metal storm shutters

In August 2008, they filed an application for political asylum. No hearing has been set. But their attorney predicts long odds because people like Gutierrez don’t precisely fit the legal definitions that require judges to grant sanctuary.

Time and money are running out as they wait in hiding for their day in court. They feel no regret abandoning old lives for the greater privilege of simply living. Gutierrez is studying English, hoping maybe one day he’ll try for a U.S. law degree.

Whatever hardships the future holds, they are hell-bent never to return to Mexico. They’ll maybe go to another country if America rejects them.

“They took everything away from us, but we are very grateful toward God because at least he’s still alive,” said Josephina. “We’ll never be the same people again.”

Part III: Denied Sanctuary; U.S. expelling terrified cartel victims

Largely outside the view of the American public, immigration authorities are vigorously opposing asylum claims filed by Mexican victims of cartel torture, extortion, kidnapping, and death sentences. Some say current refugee law just doesn’t fit their circumstances; critics, though, say that sending these people back to face their demons demeans a fundamental American ideal.

In the heat of an August day last year, 10 masked cartel gunmen roared aboard SUVs onto a street in a working class Juarez neighborhood. Four people soon lay dead amid spent AK-47 shell casings.

Two were brothers who lived with their families a few houses apart and earned extra cash as neighborhood marijuana pushers, court testimony would later show. A third victim that day was the 16-year-old son of one of the brothers, a fourth an unrelated bystander.

The gunmen issued a chilling departing vow: They’d soon return to finish off four more sons of one brother. Their newly widowed mother heard about a quick legal way

Once over the Paso del Norte pedestrian bridge in El Paso, mother and sons, ages nine through 22, joined a growing number of Mexicans petitioning for U.S. asylum as permanent haven from the narcotics traffickers besieging Mexico.

But federal immigration judges have denied them all sanctuary and are, one of their attorneys says, “sending them back to their deaths.” Two deported sons are hiding out in drug-war savaged Juarez, where murders are surging despite a military deployment.

Their mother and two brothers are awaiting a last-ditch appeal to learn whether America will send them packing too.

“(He) is a 9-year-old boy!” Pennsylvania immigration attorney CraigShagin, who is handling the case, said about the youngest son. “They’re going to take this perfectly adorable kid and throw him back into hell? Froma humanitarian point of view, this is really hard to watch.”

The family’s asylum cases and interviews with six immigration lawyers handling others show that more Mexican refugees fleeing cartel violence will soon be sent back. It’s difficult to know how judges are ruling because asylum records are not public for security reasons. But the lawyers report steep losses and few wins amid different and evolving interpretations of asylum law as it applies to Mexicans.

They say homeland security officials in some jurisdictions are aggressively opposing Mexican claims to avoid triggering a system-clogging flood of asylum petitions.

“The government is fighting them tooth and nail,” said El Paso lawyer Carlos Spector, who has lost several cases, including one by a police officer who arrived in El Paso with eight fresh bullet wounds. Spector said his four other cases are drawing unusually robust government attention.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials declined repeated requests to discuss the agency’s stance on Mexican asylum seekers.

But private attorneys facing off with ICE attorneys say they’re throwing up two main arguments: One is that the asylum statute as written doesn’t apply to victims of crime – only certain victims of political oppression, ethnic strike or civil unrest who can’t count on government protection. In the one brief statement for this story, ICE alluded to how it interprets the asylum statute.

“The men and women of ICE have a sworn duty to uphold U.S. immigration law,” the statement said. “as it is written.”

The other main government argument, known in immigration law circles as“internal relocation,” holds that victims don’t need U.S. haven because they can simply find it elsewhere within Mexico.

The asylum seekers and their lawyers strongly disagree. But there’s little indication the odds are in their favor. With few known courtroom successes, attorneys report testing out a mishmash of legal strategies.

At stake is life and limb.

Found in Juarez last month, the two brothers who fled Juarez with their mother and younger siblings last summer emerged from a house where they’ve been laying low since their April deportations. Just a few doors away the night before, masked gunmen in an SUV cornered three young men who’d been walking down the street.

The gunmen forced all three to kneel, and then executed only the young man who had the same last name as the brothers, witnesses said. A stones throwaway, the brothers said they felt embittered toward the U.S. for throwing them back into the line of fire.

Immigration authorities “treated us very badly. They gave us a completely racist treatment,” one of the brothers told the Express-News on condition their identities be withheld. “People know about the United States’ policy regarding political asylum, and we know that policy is not going to change.”

Square peg, round hole

America’s asylum law was established 30 years ago in the Refugee Act of 1980 to provide sanctuary to people whose governments don’t protect them from life-threatening persecution. All they have to do is find their own way to an American shore and request asylum from any government official.

To win asylum, they later must convince a judge they have suffered past persecution or have a well-founded fear of future persecution for one of five reasons: race, religion, nationality, political opinion and membership in a particular social group. They should also be able to show their home government either can’t protect them or is part of the problem.

Judges have extended political asylum to, among many others, Christian Iraqis forced from homes by militant Islamists, and Darfur minorities attacked by armed Sudanese government groups. But few Mexicans are ever granted asylum, government statistics indicate.

Judges have typically granted 50 or 60 a year since 2000 while total petitions ranged between 2,000 and 3,000. Asylum applications have shown an upswing since President Felipe Calderon declared war on the country’s drug cartels in 2006.

Last year, for instance, 3,229 applied compared to 2,641 in 2006, according to Executive Office of Immigration Review statistics. Some 896 Mexicans applied for asylum between January and April this year, compared to 586 for the same period in 2006.

A key legal difficulty for Mexicans, immigration experts and lawyers agree, is that the law’s five categories do not include victims of crime. Mexico’s profit-hungry drug traffickers aren’t known to target people because of race, religion, nationality or political opinion. So some of the attorneys admit they’re hunting ways to stretch the definition of one of the five categories –“social group” – to cover their clients.

“The government is basically saying they don’t fit into any of the categories,” said Eduardo Beckett, managing attorney of the Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso, which represented two of the Juarez family members who fled. His organization also has lost or had to abandon five other asylum cases and has five others.

Several immigration law specialists say the statute originally defined social group as encompassing sexual orientation, skin color, kinship ties and other “immutable characteristics” that people can’t readily change. Now, lawyers arguing for Mexican drug war refugees say subsequent case law has expanded the definition to mean specific families and people sharing social connections through professions or business.

Still, judges and courts are all over the map about what constitutes a social group. Some have accepted whistleblowers on government corruption and wealthy cattle farmers, while other courts have rejected as social groups government employees and secret informants.

Bruce Einhorn, a retired immigration judge who co-wrote the 1980 asylum statute, said judges weighing Mexican asylum cases have the discretion to accept a proposed new definition, or fall back on a literal reading of the statute, which doesn’t cover crime victims.

“It isn’t because they’re unkind, but ….. some of them view the statute very strictly,” Einhorn said. “I happen to think it’s more important to apply to law with compassion and humanity. Judges should be taking a very liberal view.”

Einhorn said there’s no political will to amend the asylum law right now to cover crime in part because “that could mean a significant chunk of a nation could flee.” Other legal analysts agree.

Unless the law is amended by an act of Congress, Mexican drug war refugees can only hope to draw an empathetic judge willing to risk appeal for humanitarian reasons — and that ICE doesn’t appeal those favorable decisions.

Asserting that organized crime victims can be members of a social group has not met with much success in other similar cases involving Latin America, an examination of court appeals shows. For instance, judges in the 1990s began rejecting asylum petitions filed by Salvadorans who claimed they formed a special group needing protection from the “Mara Salvatrucha” gang, or MS-13.

Last year, in S-E-G versus U.S. Department of Justice, the Board ofImmigration Appeals upheld a judge’s ruling that Salvadoran youths from one family targeted for forcible recruitment by MS-13 did not form a particular social group and wasn’t eligible for asylum. The panel held that any qualifying social group has to stand out in a “socially visible” way from the general population, and the Salvadoran family didn’t.

The Express-News was able to verify only one granted asylum petition in Texas. U.S. Immigration Judge David Ayala of Harlingen granted it three years ago to a kidnap victim who ran for the U.S. border after a $250,000 ransom secured his release.

The man’s lawyer, Anthony Matulewicz, argued that his client belonged to a social group, it being a wealthy class of merchants. Judge Ayala accepted the definition. But Matulewicz said he believes he won because the judge, being so close to the border, was compassionate and understood the widespread horrors of drug cartel abuses.

“You almost have to put the judge on the spot,” Matulewicz said. “Present the case in a way that’s going to break the judge’s heart. I had a good judge but I also had the facts.”

One Seattle immigration lawyer, Henry Cruz, found success for a Mexican client this year with a strategy that runs against the grain. Cruz won residency for his client claiming protection under the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

Immigration lawyers and independent legal experts alike usually dismiss the convention because it applies only when governments persecute. Yet Cruz won in a Denver court by arguing the cartels had, in effect, taken over local government institutions in Matamoros.

“It’s an up and coming argument that people will have to start using more often,” Cruz said.

‘Fear, just real fear’

The asylum cases involving the Juarez mother and her sons offers a rare glimpse into the government’s legal thinking – and the real world consequences.

After the family surrendered to American customs agents last summer, the two older sons were detained in El Paso pending the outcome of their cases. Their mother and two minor brothers were sent to a family detention center in Pennsylvania to pursue a separate claim.

Ed Beckett, attorney for the El Paso brothers, argued in part to U.S. Immigration Judge William Abbott that the brothers qualified for asylum because they belonged to an identifiable, targeted social group the government couldn’t protect – their own family.

But Abbot, in his final oral ruling in February, citing the MS-13 ruling from last year, concluded that family wasn’t a qualified social group because its members didn’t stand out from any other potential victim in Mexico, according to Beckett’s notes. Beckett said this line of legal thinking automatically excludes average people like the clients he gets.

“What’s happening in my cases is that most of my clients are not famous ort he sons of former presidents,” he said. “It means if you’re not famous or well known, you’re a nobody.”

Judge Abbot also said he believed the family could safely relocate else wherein Mexico.

Across the country in York, Pa., a similar legal fate unfolded with their mother and two younger brothers. The family’s attorney there, Craig Shagin, argued they formed a protected social group, targeted by a cartel and left unprotected by

But Immigration Judge Andrew Arthur ruled there was no evidence the family was a social group that stood out as more threatened than anyone else in Mexico. He too ruled the family could safely relocate to safer environs elsewhere in Mexico, according to a transcript.

“The court notes that Mexico is a country of over 100 million people, and that the respondent could relocate anywhere within that country and reasonably do so with family members in her hometown,” he said.

The ruling angered Shagin.

“There is no safe haven in Mexico; it’s a fiction,” he said. “The people in the country can’t figure out who is and who isn’t working for the dark side.”

Last month, an immigration appeals panel upheld the judge’s ruling. Deportation orders were issued. Shagin has staved them off by filing another appeal with the U.S. 3rd Circuit Court. If he loses, and his client wants to wait in detention, he could appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The mother declined to be interviewed. But Shagin said that when consulting with her he senses “fear, just real fear, a feeling of ‘what do I do if we go back?’ You hear them sighing all the time, not wailing and crying, just completely at a loss as to what to do and a feeling of desperation. Tome, it is very sad.”

Her two sons already on the ground in Juarez say they are so riven by fear they rarely leave the house where they’re holed up. The month of June brought the number of murders for the year to 886, up nearly 70 percent over the first six months of last year, the newspaper Diario reported. Last year, Juarez’s murder rate by far led the nation with 1,607 killed.

The brothers believe the cartels never forget an enemy and could turn them into a statistic at any time for whatever their father’s sin was.

“They have killed innocent people who were not involved (in the drug business) and they threatened to finish off all of us,” one said. “That’s why we are scared.”

Part IV: Mexico’s wealthiest drug war refugees buying U.S. haven

Tens of thousands of Mexico’s most affluent citizens are fleeing to Texas and other states by securing obscure business visas that allow them to buy or invest on the American side. It’s an exodus that Latino leaders are comparing to the mass departure of Cuba’s ownership class after Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution. War-weary families are arriving on midnight flights after nightmares with kidnappers – heinous ordeals that leave them lacking limbs, ears and fingers; one lawyer tells about a well-heeled client who arrived catatonic after kidnappers chopped off a foot and sent it back to the familiy. They are able to legally and easily flee by buying businesses here, sometimes with no serious intention of turning a profit.

SAN ANTONIO, TX. — Hard work and acumen earned Pierre Oliver Gama Valdes fabulous affluence at 34.

As a Mexican living in the sprawling capital of Mexico City, however, neither wit nor wealth could protect his family from criminal gangs’ extortionist threats. On the contrary, success made Gama-Valdes a marked man, and left him in constant fear for his wife and two children.

In the U.S., however, Valdes’ money grants him privileges — explicit ones, sanctioned by the federal government. A $100,000 investment and a bit of

Gama-Valdes, an energetic, athletically built man with intense brown eyes, is part of a new immigration phenomenon: Tens of thousands of Mexico’s most affluent and entrepreneurial citizens are fleeing to California, Texas and other states by securing obscure U.S. business visas that allow them to buy or invest in various enterprises. In his case, an escalating series of kidnappings, threats and the disappearance of a close friend’s child prompted a quite legal flight north to safer environs.

“That’s when I started thinking, ‘I’ve got to leave this place,’” said Gama-Valdes, who has two young children. “You see the whole world differently when you have childrens. Before something more happened to them, I wanted to get out of Mexico.”

Incoming refugees like him are the elite upon which Mexico had been building its economic development, until President Felipe Calderone launched his crackdown on the country’s vicious drug gangs.

Now, they form an exodus that some Latino leaders are comparing in smaller scale to post-Castro departure of Cuba’s ownership class after the 1959 revolution. War-weary families are arriving on midnight flights after nightmares with kidnappers — heinous ordeals that leave them lacking feet, ears and fingers; one lawyer told GlobalPost about a client who arrived catatonic after after kidnappers chopped off a foot and sent it back to the family.

“The scale is larger than anything we have seen in 80 years,” said prominent San Antonio business leader Henry Cisneros, the former U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary. “This trickle is growing into a very stout current. Virtually everyone I talk to cites examples of people in their circles of family and friends who have been robbed or kidnapped who are coming here.”

These business class refugees are exploiting an obscure set of American resident visas known as the “E” and “L” series. The visas allow wealthy Mexicans to essentially buy their way out of immigration entanglements that commonly block their less affluent countrymen, simply by purchasing or launching businesses — regardless of their language skills or personal ties to the

To fulfill the visa requirement, they are opening restaurants, storage facilities, import-export companies, and even a strip club stateside. And in an unusual turn of events, in the midst of the economic crisis, many southwestern cities that have had an uneasy relationship with Mexicans spilling across the borders are now seeking them out. San Antonio, for one, has opened foreign outreach offices to facilitate and welcome them.

Gama-Valdes typifies many of the city’s most recent newcomers.

In August, along with his business partner Manuel Octavio Espejo Pantoja, he bought a tiny cafe in north San Antonio on an L visa. Then they simply moved their families to town, with instant legal residency.

Ironically, it was Mexico’s drug war and criminal legacy that helped make Gama-Valdes and Espejo-Pantoja rich. They built a thriving firm that sells body armor and rents out guards, and they own a private nationwide mail service for banks, many of which don’t trust the government system. The businesses, which employ some 500 people in Mexico, are now being run by associates without the means to flee. Gama-Valdes still manages his businesses but from the safety of the U.S.

Inside their new restaurant, amidst take-out menus, faux-granite tables and freshly-painted peach-colored walls, the men recount an escalating series of extortion plots, kidnappings and death threats against their families.

They recount an escalating series of incidents that include short-term “express kidnappings” for ATM money and threats.

As part of an extortion attempt six months ago demanding two million pesos, someone placed a funeral wreath at Espejo-Pantoja’s home doorstep bearing the name of his youngest daughter. That was the final straw for both partners.

Gama-Valdes and Espejo-Pantoja say their last concern is whether the restaurant ever turns a profit. Neither have any prior restaurant experience.

“I am willing to take losses as long as it keeps me in America,” Gama- Valdes says. “This is all about my kids.”

Business leaders, lawyers, advocates say these new drug war immigrants are America’s gain. They are coming with new businesses, personal fortunes, higher education diplomas, and with their most prized of their possessions: loved ones.

A class divide

In contrast, less affluent drug war refugees taking flight, such as municipal cops, journalists and peasants, face U.S. detention, deportation proceedings or chancy political asylum petitions.

As GlobalPost has reported, http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/mexico/us-asylum-cases-mexico?page=0,1), political asylum route is complex, time consuming and unpredictable. Some U.S. immigration judges reject well-documented asylum claims on grounds that the law doesn’t squarely apply to victims of crime. Some panicked families have been sent packing back to Mexico.

“The situation is bad, but not asylum bad,” said Ramone Curiel, a San Antonio immigration lawyer who reports a significant upswing in E and L visa business. “People come to me and say we’re high profile and there’s a possibility of a kidnapping. But when I tell them about the asylum process their minds shut off. I pretty much steer them away from

The E-1 and E-2 visas give residency leading to citizenship for Mexicans who are involved in trade or invest in certain types of U.S. businesses, renewable upon government inspection every three to five years.

L visas enable business people, generally in an executive or specialized role, who are in Mexico and working for foreign companies, to transfer themselves and family to the U.S.

American consulate officers review the applications. Consideration does not take into account fear of criminal gangs, only that financial performance requirements are met, said Edward McKeon, minister-counselor for Consular Affairs at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City.

“We don’t care why they want to do it,” he said. “If they’re qualified, we issue them. They might want to go to be closer to their girlfriend. We don’t care. In fact, that’s probably a good reason.”

Exact numbers of wealthy Mexicans taking advantage of the visas is unknown because data from the past year – a period for which the numbers are predicted to be

But State Department consular officers in 10 issuing posts scattered along the U.S. Mexico border and the interior – more than any other nation – are keeping very busy.

Immigration statistics published by homeland security show the number of issued E visas more than doubled from 7,893 in 2005, just before President Felipe Calderon mounted his war against drug cartels, to 16,411 in the first nine months of 2008. The number of L visas issued during the same time periods jumped from 25,429 to 33,675. California is the top destination, followed by Texas.

But reports indicate that 2009 will be a banner year. As lawlessness throughout Mexico has intensified, especially extortion and kidnap plots targeting anyone perceived as wealthy. Many thousands of wealthy, educated Mexicans have been swept up by this northward tide, according to interviews with the immigrants and with American business leaders, realtors, trade associations and with seven U.S. immigration lawyers handling their visa applications.

San Antonio has emerged as an epicenter for this surge, although San Diego, Los Angeles and other border state cities get their fair share. Estimates tend to fluctuate rather wildly.

Some local business leaders and service industry professionals who help with relocation offering unsubstantiated estimates ranging from 30,000 in the last two years to as high as 100,000 for San Antonio alone.

Luis Escobar, himself a kidnap survivor who made his move on an L visa six years ago, runs a San Antonio company that specializes in helping wealthy Mexicans relocate their businesses and families. He’s brought 259 families to San Antonio since January.

But Escobar said his outreach in Mexico has overwhelmed his capacity, bringing in more than 23,000 inquiries so far this year.

“The reason is Calderon’s decision to fight against the drug dealers and the violence,” he said. “Because of the situation, these Mexicans are looking for another option to live.”

A brutalized elite

The new arrivals are showing up defeated and downtrodden, with horror stories of kidnappings, torture and extortion, Escobar and others say. Some have arrived with freshly missing fingers and ears cut off by kidnappers eager to up the size and speed of ransom payments.

Some two dozen of these new arrivals, through intermediaries, declined GlobalPost interview requests over several months on grounds that they fear jeopardizing loved ones and businesses they tend on furtive cross-border visits.

“The problem with them talking is that they have links in Mexico, and if they talk

Professionals who deal directly with the new immigrants, such as real estate agents and attorneys, describe a population of walking wounded.

Escobar, for instance, recounts a wealthy tycoon who showed up in San Antonio last month, missing a foot.

The businessman’s kidnappers hacked off the foot at the ankle without anesthesia, he said, and sent it to family members to urge faster ransom payment. As soon as they secured the businessman’s release, the family fled to San Antonio and became Escobar’s clients, first so the victim could be committed to psychiatric facility and second so no one would have to return.

Escobar is now helping the family arrange L visas so the man and his family can stay.

Another family walked into Escobar’s offices this summer after kidnappers released his traumatized but alive son with a message cut into his chest that read: “Next time, when we say $500,000, we mean $500,000.”

Still another wealthy executive arrived with his family in San Antonio last month, catatonic. Escobar said the client’s captors had forced him to spend 35 days in an underground water storage tank before ransoming his freedom. A blindfold that never once came off has permanently disfigured the man’s face.

“In my company, we know people who have had one of the these events have to be taken care of in a very different way because one can make bad decisions out of fear, the wrong decisions,” he said. “The people cry in my conference room. What can you tell them? You have no clue what these incidents do to these people.”

Other Texas immigration lawyers report similar stories.

Anthony Matulewicz, an immigration lawyer in McAllen, Texas, says E and L visas have practically overtaken his practice over the last two years. Many of his clients are extremely wealthy but that didn’t protect one from having four of five fingers on one hand chopped off.

After facilitating E visas, Matulewicz reports that his clients have relocated with a wide range of businesses, including a strip club, storage facilities

Tragedy’s bounty

Although they are loath to say so, San Antonio city boosters know Mexico’s tragedy is America’s gain. Those coming are opening huge bank and investment accounts, buying real estate, shopping and enrolling studious children in local schools.

San Antonio has kept foreign trade offices in Monterrey, Gaudalajara and Mexico City for years. But these days, those offices are seeing a new acute receptiveness in the city’s sales pitches, said Beth Costello, director of the city’s international affairs department.

Costello wouldn’t give figures but said the city has become well aware that “people are increasingly uncomfortable in Mexico… and if people come and open their businesses in San Antonio, we want Mexican citizens to feel comfortable.”

Patricia Stout, who owns a large travel agency in San Antonio, has served as an officer for a local Mexican business association called The Impresarios, which is involved in the Mexico outreach effort. The group routinely sends emissaries to stage seminars in Mexico. These are aimed at luring businesspeople who are already predisposed to leave their country for security reasons.

The response has been overwhelming this year and last, she said.

“This is a phenomenon,” Stout said. “ The people who are doing it are people who can afford it. These people are bringing businesses. They shop like crazy. They buy homes. They buy cars. People with money and education are coming here to make their new life. That is something worth talking about.”