Since 9/11, authorities have apprehended thousands of “special interest aliens” from Islamic countries crossing U.S. borders. If authentic war refugees could use the underground railroad, why not equally determined terrorists? For Hearst News, Bensman retraced the steps of an Iraqi war refugee who swam the Rio Grande on April 29, 2006. Bensman traveled to Syria, Jordan; Guatemala, Mexico, and the Texas border.

*Winner of the 2008 National Press Club Edwin M. Hood Award for Diplomatic Correspondence

*Winner of the 2008 Inter-American Press Association’s award for in-depth reporting

*Winner of the 2008 Texas Institute of Letters Stanley Walker Award for Best Work of Newspaper Journalism

*First Place Winner of the 2008 Houston Press Club For Investigative Reporting

DAMASCUS, Syria — Al Nawateer restaurant is a place where dreams are bartered and secrets are kept.

Dining areas partitioned by thickets of crawling vines and knee-high concrete fountains offer privacy from informants and agents of the Mukhabarat secret police.

The Mukhabarat try to monitor the hundreds of thousands of Iraq war refugees in this ancient city, where clandestine human smuggling rings have sprung up to help refugees move on — often to the United States.

But the young Middle Eastern men who frequent Al Nawateer, like Iraqi war refugee Aamr Bahnan Boles, are undaunted, willing to risk everything to meet a smuggler. They come to be solicited by someone who, for the right price, will help them obtain visas from the sometimes bribery-greased consulates of nations adversarial or indifferent to American security concerns.

Night after night, Boles, a lanky 24-year-old, sat alone eating grilled chicken and tabouli in shadows cast by Al Nawateer’s profusion of hanging lanterns. Boles always came packing the $5,000 stake his father had given him when he fled Iraq.

Boles was ordering his meal after another backbreaking day working a steam iron at one of the area’s many basement-level garment shops when he noticed a Syrian man loitering near his table. The Syrian appeared to be listening intently. He was of average build and wearing a collared shirt. Boles guessed he was about 35 years old.

When the waiter walked away, the Syrian approached Boles, leaned over the cheap plastic table and spoke softly. He introduced himself as Abu Nabil, a common street nickname revealing nothing.

“I noticed your accent,” the Syrian said politely. “Are you from Iraq?”

Boles nodded.

“I could help you if you want to leave,” the Syrian said. “Just tell me when and where. I can get you wherever you want to go.”

For an instant, Boles hesitated. Was the Syrian a Mukhabarat agent plotting to take his money and send him back to Iraq? Was he a con artist who would deliver nothing in return for a man’s money?

“I want to go to the USA,” Boles blurted.

“It can be done,” said the Syrian. But it wouldn’t be cheap, he warned. The cost might be as high as $10,000.

Hedging against a con, Boles said he didn’t have that kind of money.

The Syrian told him there was a bargain-basement way of getting to America. For $750, he could get Boles a visitor’s visa from the government of Guatemala in neighboring Jordan.

“After that you’re on your own,” the Syrian said. “But it’s easy. You fly to Moscow, then Cuba and from there to Guatemala.”

The implication was obvious. The Syrian would help Boles get within striking distance of the U.S. border. The rest was up to him.

Boles knew it wouldn’t be easy or quick. Not until a year later, in fact, in the darkness just before dawn on April 29, 2006, would he finally swim across the Rio Grande on an inner tube and clamber up the Texas riverbank 40 miles west of Brownsville near the international bridge at Los Indios.

Boles, in cutting his deal with the Syrian, set in motion a journey into the vortex of a little-known American strategy in the war on terror: stopping people like him from stealing over the border.

The deals cut at places like Al Nawateer could affect America. Americans from San Antonio to Detroit might find themselves living among immigrants from Islamic countries who have come to America with darker pursuits than escaping war or starting a new life.

U.S.-bound illicit travel from Islamic countries, which started long before 9-11 and includes some reputed terrorists, has gained momentum and worried counterterrorism officials as smugglers exploit 2 million Iraq war refugees.

A stark reminder of U.S. vulnerability at home came this month when six foreign-born Muslims, three of whom had entered the country illegally, were arrested and accused of plotting to attack the Army’s Fort Dix in New Jersey.

What might have happened there is sure to stoke the debate in Congress, which this week will take up border security and immigration reform.

Politically, immigration can be a faceless issue. But beyond the rhetoric, the lives of real people hang in the balance. A relatively small but politically significant number are from Islamic countries, raising the specter, some officials say, of terrorists at the gate.

River of immigrants

Near the tiny Texas community of Los Indios, the Rio Grande is deep, placid and seemingly of little consequence.

But its northern bank is rigged with motion sensors that U.S. Border Patrol agents monitor closely, swarming whenever the sensors are tripped.

Here and all along the river, an abstract concept becomes real. America’s border with Mexico isn’t simply a political issue or security concern. It is a living body of water, surprisingly narrow, with one nation abutting its greenish-brown waters from the north and another from the south.

Since 9-11, the U.S. government has made guarding the 1,952-mile Mexican border a top priority. One million undocumented immigrants are caught each year trying to cross the southern and northern U.S. borders.

Because all but a tiny fraction of those arrested crossing the southern border are Mexican or Central American, issues of border security get framed accordingly and cast in the image of America’s neighbors to the south. Right or wrong, in this country the public face of illegal immigration has Latino features.

But there are others coming across the Rio Grande, and many are in Boles’ image.

People from 43 so-called “countries of interest” in the Middle East, South Asia and North Africa are sneaking into the United States, many by way of Texas, forming a human pipeline that exists largely outside the public consciousness but that has worried counterterrorism authorities since 9-11.

These immigrants are known as “special-interest aliens.” When caught, they can be subjected to FBI interrogation, detention holds that can last for months and, in rare instances, federal prison terms.

The perceived danger is that they can evade being screened through terror-watch lists.

The 43 countries of interest are singled out because terrorist groups operate there. Special-interest immigrants are coming all the time, from countries where U.S. military personnel are battling radical Islamist movements, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and the Philippines. They come from countries where organized Islamic extremists have bombed U.S. interests, such as Kenya, Tanzania and Lebanon. They come from U.S.-designated state sponsors of terror, such as Iran, Syria and Sudan.

And they come from Saudi Arabia, the nation that spawned most of the 9-11 hijackers.

Iraq war refugees, trapped in neighboring countries with no way out, are finding their way into the pipeline.

Zigzagging wildly across the globe on their own or more often with well-paid smugglers, their disparate routes determined by the availability of bogus travel documents and relative laxity of customs-enforcement practices, special-interest immigrants often converge in Latin America.

And, there, a northward flow begins.

Steve McCraw, director of the Texas Department of Homeland Security and a former assistant director of the FBI, said the nation’s vulnerability from this human traffic is unassailable — even if not a single terrorist has ever been caught.

“This isn’t a partisan issue,” McCraw said. “If the good guys can come, you know, then so can the bad guys. We are at risk.”

Though most who cross America’s borders are economic migrants, the government has labeled some terrorists Their ranks include:

Mahmoud Kourani, convicted in Detroit as a leader of the terrorist group Hezbollah. Using a visa obtained by bribing a Mexican official in Beirut, the Lebanese national sneaked over the Mexican border in 2001 in the trunk of a car.

Nabel Al-Marahb, a reputed al-Qaida operative who was No. 27 on the FBI’s most wanted terrorist list in the months after 9-11, crossed the Canadian border in the sleeper cab of a long-haul truck.

Farida Goolam Mohammed, a South African woman captured in 2004 as she carried into the McAllen airport cash and clothes still wet from the Rio Grande. Though the government characterized her merely as a border jumper, U.S. sources now say she was a smuggler who ferried people with terrorist connections. One report credits her arrest with spurring a major international terror investigation that stopped an al-Qaida attack on New York.

The government has accused other border jumpers of connections to outlawed terrorist organizations, some that help al-Qaida, including reputed members of the deadly Tamil Tigers caught in California after crossing the Mexican border in 2005 on their way to Canada.

One U.S.-bound Pakistani apparently captured in Mexico drew such suspicion that he ended up in front of a military tribunal at Guantanamo Bay.

“They are not all economic migrants,” said attorney Janice Kephart, who served as legal counsel for the 9-11 Commission and co-wrote its final staff report. “I do get frustrated when people who live in Washington or Illinois say we don’t have any evidence that terrorists are coming across. But there is evidence.”

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection apprehension numbers, agents along both borders have caught more than 5,700 special-interest immigrants between 2001 and the fall of 2007. But as many as 20,000 to 60,000 others are presumed to have slipped through during that time, based on rule-of-thumb estimates typically used by homeland security agencies.

“You’d like to think at least you’re catching one out of 10,” McCraw said. “But that’s not good in baseball and it’s certainly not good in counterterrorism.”

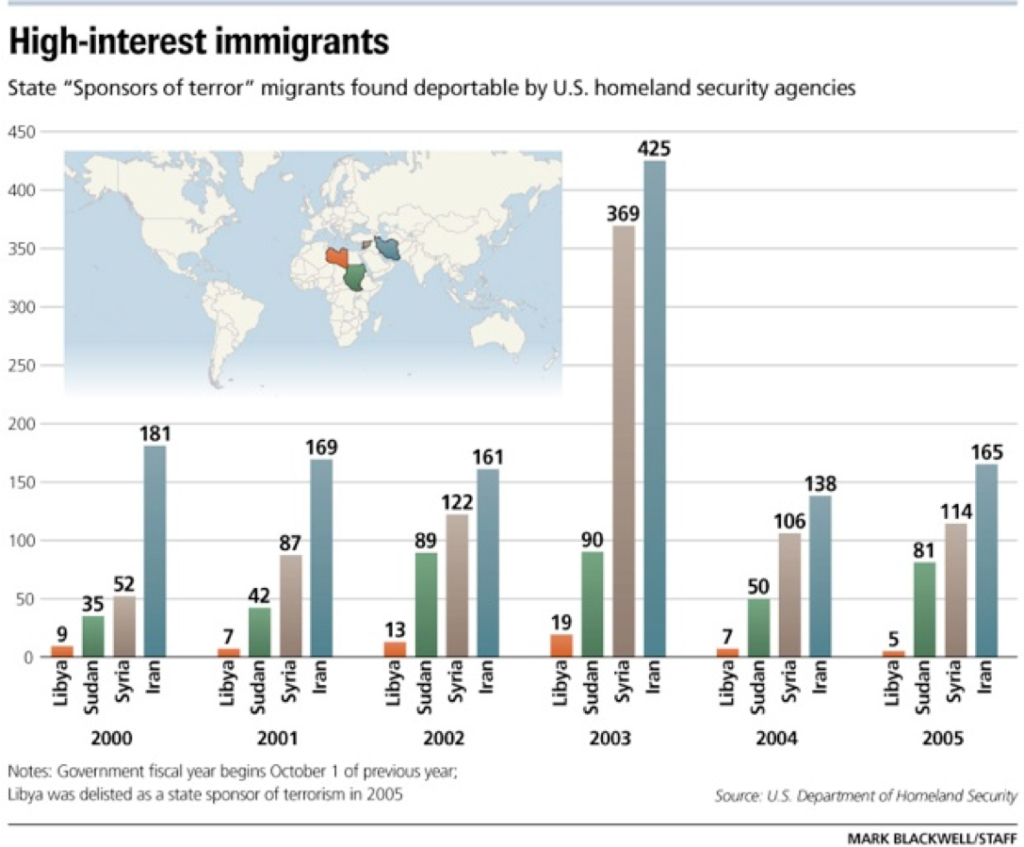

Other federal agencies besides the Border Patrol have caught thousands more of the crossers inland after it was discovered they were in the country illegally, including 34,000 detainees from Syria, Iran, Sudan and Libya between 2001 and 2005, according to a homeland security audit last year of U.S. detention centers for immigrants. Then there is an unknown number caught by Mexico — an inveterate partner, as it turns out.

Texas accounts for a third of all the special-interest immigrants caught by the Border Patrol since 9-11, including 250 apprehended between March 2006 and February.

Efforts to stop the traffic are, in some ways, beyond U.S. control. Corrupt foreign officials and bureaucrats in Latin American consulates and in the Middle East have sold visas. Others hand them out without taking U.S. security concerns into account.

Anti-U.S. sentiments run deep in nations across the globe, creating steppingstones to America for those whose illicit travel plans sometimes are abetted with delight.

The story of Boles’ journey to America — born over a plate of tabbouleh, orchestrated by a polite smuggler and culminating with an early-morning river crossing at Los Indios — serves as a lens on the pipeline and raises legitimate questions.

If an Iraqi Christian with few resources and little more on his mind than fleeing a war for a better future in America can make his way from a designated state sponsor of terror like Syria for less than $4,000, then why couldn’t a well-financed Muslim terrorist of equal determination?

Who else besides Boles has crossed the Rio Grande, and with what intent?

The answers figure to inform public policy for years to come.

Top U.S. political leaders have repeatedly cited the prospect of terrorist infiltration to double public expenditures on the borders from $4 billion in 2001 to more than $10 billion now; to deploy National Guard units; and to launch nationally divisive immigration reform legislation.

Lesser-known American enforcement initiatives abroad have involved the CIA, the FBI, the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard and Drug Enforcement Administration agents.

(The FBI and Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Washington, D.C., did not reply to phoned and written requests for comment on this series.)

Many question the extent of the threat, especially opponents of various immigration-control proposals.

There is evidence, primarily a decline in traffic, that the border crackdown is discouraging illegal immigration. Would-be immigrants in Guatemala and Syria told the San Antonio Express-News they didn’t want to risk getting caught and so had decided not to try crossing the border.

For a terrorist who wants to infiltrate, “It is high risk, being smuggled in, because there is an active effort to clamp down,” said Laura Ingersoll, an assistant U.S. attorney in Washington who has prosecuted many smuggling rings.

A newly declassified Homeland Security Department survey of 100 captured Iraqi, Somali and Eritrean migrants cites intelligence that al-Qaida planners view border infiltrations as a “secondary” alternative to entering legally with official documents.

Though the Texas Legislature this month passed Gov. Rick Perry’s $100 million border-security proposal, some lawmakers have belittled the idea that terrorists might blend in as a politically expedient cover for a racist anti-Mexican agenda.

Texas Rep. Rick Noriega, D-Houston, who commanded a National Guard unit in the Laredo area, said Middle Eastern immigrants don’t worry him because they only come across in “onesies and twosies.”

“Is it possible that someone could cross our border and come into Texas and do bad things? Absolutely.” Noriega said. “But then you have to deal with probability. I’m extremely skeptical of painting the picture that the reason we’re doing border security is so terrorists don’t come across. I don’t think you scare the public using 9-11. That’s a little old.”

The strangers within

Noriega’s reservations notwithstanding, few in America question whether U.S. policymakers and counterterrorism officials should react somehow to the influx of immigrants from Islamic countries. As the Fort Dix case suggests, there are strangers among us whose hearts may ultimately be unknowable.

Uncertainty about the allegiance of immigrants is illustrated by the Boles case.

Who or what is he and why did he come to America? How can his story be vetted, his mind and motives plumbed?

Boles told U.S. authorities that he is a Chaldean Christian from the Iraqi town of Bartella, near Mosul — a persecuted ethnic minority with origins in the Eastern Christian tradition but with long ties to the Roman Catholic Church.

A federal prosecutor in South Texas would test Boles’ religious beliefs by grilling him about the Bible, Jesus and Christian practices such as communion.

Here’s the story of Boles’ life as he tells it.

Before the Iraq war, he, his parents, two sisters and brother scraped by on what was left of a once-productive farm that had been mostly confiscated by the regime of Saddam Hussein and distributed to Sunni Arab Muslim herders.

His father and brother ran a taxi service to bring in extra cash.

After the war started, Islamic extremists began preying on Iraqi Christians, uprooting them from schools, jobs and businesses, often on the charge that they were “infidels” collaborating with U.S. forces. The extremists kidnapped some Christians and killed others, focusing on the men.

As Boles later would say, “The Muslims would decapitate me for belonging to Christianity.”

In January 2004, Boles’ father sent him to Syria with a large portion of the family’s savings: $5,000. It was enough, perhaps, to buy passage to America, where he would be safer.

Six months later, Boles’ brother died in a car crash and his father ordered him not to return, lest he lose his only remaining son. A kidnapped uncle was murdered even though the ransom was paid.

Boles never had given much thought to living in America, though he had an uncle in Sterling Heights, Mich. And it wouldn’t be easy leaving Syria; the heavily fortified U.S. embassy in Damascus, which has been the target of suicide bombing attempts that ended in gunbattles, wasn’t giving out many visas.

Boles was trapped.

As did hundreds of thousands of others who fled to Damascus when sectarian violence in Iraq broke out, he had settled in among the tiny tenement apartments in a suburb known as Jaramana.

Locals today call the neighborhood “Little Fallujah” because of the influx of Iraqis. Small Iraqi-run bakeries, Internet cafes, hair salons and laundry cleaners had sprung up all over town, many of them bearing the Iraqi national flag painted on their windows.

Boles lived on the sixth floor of a building that housed a garment shop where he worked 12-hour days ironing clothing bound for the big markets, or souks, of Damascus. Even though such shops are all over Little Fallujah, Boles was lucky to find a job in one. Steady-paying jobs anywhere in Syria are hard to come by and jealously guarded by working-class Syrians.

For most refugees, returning to Iraq was, then as now, out of the question. So was staying in Syria and Jordan, where local economies couldn’t absorb them. But almost every other country in the world, including the United States, was handing out legal visas only grudgingly.

Not surprisingly, smugglers had picked up the slack.

the same neighborhood where he took refuge. Photo: Bensman

The smuggling business in Damascus and Amman was deep underground. Smugglers and their agents hovered in the shadows of places like Al Nawateer, at the Iraqi bakery just up the street and at the brothels where Iraqi women catered to Iraqi men.

Refugees tell of well-oiled Arab mafias, based in South Africa; of an Iraqi Kurdish group living in Sweden that fields recruiters in Jordan; and of local Syrian groups that specialize in guiding paying clients into Turkey and Greece, which are considered launching pads for illegal passage to any other country in the world.

Refugees with little or no means are left to register with the United Nations, apply for visas and resign themselves to the real possibility of never leaving. But for those who have enough money, there are many ways to escape.

“They’re here. They’re everywhere,” said Joseph Dauvod, an elderly Iraqi refugee who once paid a smuggler to get him to the U.S. but got caught crossing the Turkish border. “It’s just that no one knows who they are until they approach you. I know so many people who have left that way from here.”

Ahmad Ali, a 21-year-old Iraqi Sunni Muslim living in Amman, has made several attempts to get himself and his mother to Sweden, whose lenient asylum laws and immigration regulations have made it the most popular destination in Europe for Iraqi refuges.

Ali said he paid a local smuggler $4,000 last year to get him into Sweden, but border guards arrested everyone in his group.

In March, he said, he and his mother traveled on legal visas to Turkey to try again. In Istanbul, he connected with an Arab smuggling group based in South Africa. His mother paid $16,000 for her own passage to Stockholm.

“It was all-inclusive, hotel, food, plane tickets to Stockholm,” Ali said.

The group delivered, as part of the package, Ali said, “a legal, original Venezuelan passport,” which his mother used to board a plane from Turkey to Stockholm. When she landed in Stockholm, she destroyed the passport, claimed political asylum and is laying plans to get her last son, Ali, to Sweden.

Such stories abound in the streets and coffee shops of Syria and Jordan. Those who are actively in the market know the price lists well enough to recite them by heart.

“If you are an Iraqi and you stand by the corner of the Grand Mosque (in the Old City of Damascus), they’ll come right up to you and say, ‘When do you want to go?'” said Omar Emad, an Iraqi refugee who has been unable to save enough money to pay a smuggler.

“All you have to do is stand there.”

in Damascus. Photo: Bensman

Smugglers are known to offer discounts to persuade travelers to cross at the Texas border instead of California. The Texas border, at least in recent times, was considered more porous and the journey through Mexico less risky.

Smugglers also offer needy clients sliding pay scales. American court records from a half-dozen smuggling prosecutions show that well-heeled Middle Eastern travelers have paid upward of $25,000 a person for illegal passage through Latin America to get over U.S. borders. Often, they have entered through Canada — after first arriving in Latin America, like Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia.

Many routinely paid smugglers $8,000 to $10,000 a person. Whatever the cost, many of the trips can’t be done for anyone — rich or poor — without the vital enabling role of foreign embassies or consulate offices, often those of Latin American nations that are based in the Middle East.

Boles, who earned about $180 a month at his steam iron, worked for only one reason: to protect his precious bundle of U.S. dollars that he knew was the key to America’s back door.

And they disappear

The man who would help Boles leave Syria probably was a small independent operator or a recruiter for larger organizations that paid commissions.

They met at Al Nawateer, a restaurant popular with young lovers and businessmen as well as refugees.

The smuggler, who said his name was Abu Nabil, offered to take Boles’ Iraqi passport to Jordan and get it stamped at a Guatemalan consulate office. The two men would meet again, they resolved, when the smuggler returned to Damascus, with Boles forking over $750 for his stamped passport

They agreed to the deal and parted ways — each leaving Al Nawateer, Boles probably forever.

Al Nawateer’s friendly, backslapping manager, Haithem Khouri, remembers Boles and how he vanished. It’s not unusual. Table 75, for instance, is a gathering place for larger groups from which patrons simply disappear.

“They come in every day to eat, drink and then, one day, they’re just missing and I ask, ‘What happened?'” Khouri said.

But he knows, or has a pretty good idea. Those who vanished went to America. Or Europe. Refugees themselves tell of friends and whole families happily reporting back from new homes half a globe away. Those who leave almost invariably do so without saying goodbye because advertising their illegal travel plans would imperil smuggler and refugee alike.

Boles did not see Abu Nabil again for two months. Then one day the smuggler rang his cell phone. When the call came, Boles was resting in his small dormitory-style apartment. The walls were bare, and there was a radio.

“I have your passport,” the smuggler said. “Where do you want to meet?”

They met outside Al Nawateer. It was dark. Boles opened his passport under a streetlight and saw that it was indeed stamped with a three-month visa to Guatemala. It looked official, but he wondered aloud if it was real.

“It’s real,” the man assured Boles. “And no one will ask any questions in Guatemala.”

Boles handed the smuggler $750 and the two went their separate ways.

Boles had known better than to ask the question that had been on his mind for weeks. Why would Guatemala, of all countries, keep a consulate office in the Middle East that was willing to hand out visas to Iraqis when few others would?

The answer is that some foreign embassies and consulate offices based in the Middle East have no qualms about providing Iraqis and local citizens with visas that enable them to get within striking distance of a U.S. border. One of them is the Guatemala consulate office in Jordan.

The consulate is about 150 miles southeast of Damascus, in Amman. A blue and white national flag of Guatemala snaps atop a 20-foot flagpole on a busy street in the financial district. The flag advertises the presence in a strip shopping center of Guatemala’s “Honorary Consul” in the Kingdom of Jordan: Patricia Nadim Khoury, who represents Guatemala’s foreign affairs from a home-furnishings shop catering to Amman’s wealthy.

This is the only place that Boles’ smuggler could have secured a real Guatemala tourist visa.

One day recently, Khoury, a petite auburn-haired woman who appears to be in her mid-30s, sat behind a heavy oak desk as workers finished renovating the store.

She wore a blue denim jacket with slacks and a red sweater tied around her waist.

After agreeing to a brief interview, Khoury said she was born in Guatemala and took over honorary consul duties from her father when he died seven years ago. Most people who apply for visitor’s visas, she said, are Jordanians, Syrians and a few Iraqis.

Several thousand Palestinians, Jordanians and other Arabs, as well as their descendants, have lived in Guatemala City for decades.

The country’s rules for acquiring tourist visas require applicants to show bank statements for three months and demonstrate that they have credit cards. Citizens of the U.S. and most European countries can apply by mail.

Although it’s unclear whether Iraqis and other Middle Easterners are required to personally appear to apply, Khoury said she interviews every applicant before issuing a visa, in part to determine whether they are trying to cross illegally into the U.S.

“I don’t give visas to people who don’t come personally here.” Khoury also said she requires bank statements and other documents from applicants in addition to the personal interviews.

When asked how Boles and several other Iraqis might have obtained Guatemala visitor’s visas from her office without showing up, Khoury offered, “Maybe it’s not a legal visa.”

Khoury said she would not accept payment in exchange for issuing visas to an unqualified applicant and that no one ever offers.

“If someone came and asked, I would kick him out,” she said. “I can maybe get the police.”

A mile away, another honorary consul spoke freely of how money makes things happen in a society where bribes are an accepted means of doing business.

“I’ve been offered lots of money — thousands of dollars,” said Raouf N. El-Far, a Jordanian businessman who was appointed Mexico’s consul to Jordan in 2004.

is routinely offered thousands in bribes for travel visas

to Mexico. Photo: Bensman

The bribe offers come from Iraqis, Syrians and Jordanians, many of whom openly disclose plans to get themselves smuggled over the U.S. border once in Mexico, El-Far said. One man recently offered to pay him $10,000 to secure a tourist visa for an Iraqi. If all went well, the man said, he would bring El-Far 10 Iraqis a month at the same price, a pipeline amounting to $100,000 in bribes every 30 days.

Is he tempted by such offers?

El-Far chuckled. “Yes, I am,” he said.

But, then, turning serious, he said he does not take bribe money “because it’s against my principles.”

Under U.S. pressure after 9-11, El-Far said, Mexican intelligence services for the first time conducted a background investigation on a Jordanian consul. The check, he said, was so thorough “they wanted to know how many times I kissed my wife before I go to bed.”

Khoury and El-Far acknowledged granting visas on a regular basis to Middle Easterners who meet the requirements for documentation. But they said they can’t thoroughly check the veracity of the papers and the travelers’ stated plans.

“It’s not my business to guard against this,” Khoury said.

The U.S. Justice Department has prosecuted nearly a dozen major smuggling rings that specialized in moving Middle Eastern clients since 9-11.

The majority of the smugglers planned to bring their clientele into South American countries, such as Ecuador, Peru and Colombia, and Guatemala, to prepare them for the final trip north.

Smugglers could simply buy visas outright from corrupt consular or embassy officials, according to these court records. For example, before U.S. and Mexican authorities shut his organization down, Salim Boughader-Mucharrafille, a Mexican national of Lebanese descent, smuggled hundreds of fellow countrymen from Tijuana into California. The scheme involved bribing Mexican consular officials.

Venezuela is another jumping-off point to the American border, according to court records of smuggling cases.

Because of its antagonistic relationship with the United States, Venezuela does not cooperate on counterterrorism measures, according to the U.S. government, and shows no concerns about issuing visas to special-interest migrants.

One day recently, the Venezuelan Embassy in Damascus, its walls bedecked with large portraits of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, was packed with Syrians seeking one of nine types of visas offered.

The U.S. State Department has complained in recent years about Venezuela’s cozy relationship with Syria and Iran. Earlier this year, the first nonstop flights began from Tehran, Iran, to Caracas, Venezuela — a development that some U.S. counterterrorism specialists say opens a new avenue for potential terrorists to the American border.

Some of the government’s most senior Homeland Security officials have spoken of yet another source of terrorist infiltrators: the area where Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina meet, known as the “Tri-Border” region.

Tens of thousands of Arab immigrants there have been under scrutiny by American intelligence services since 9-11. The U.S. Treasury Department in December named people and organizations that “provided financial and logistical support to the Hezbollah terrorist organization.”

Last year, Gen. Bantz J. Craddock, commander of the U.S. Army’s Southern Command, warned the House Armed Services Committee that some of these groups “could move beyond logistical support and actually facilitate terrorist operations.”

Kephart, the lawyer who served as counsel to the 9-11 Commission and co-wrote the final report, testified in March 2005 before the Senate Judiciary Committee about a classified document she’d seen while serving on the commission.

She said the document, which since had been declassified, was a Border Patrol report about meetings in Spain between members of al-Qaida and a Colombian guerrilla group. A topic of discussion at the meeting, Kephart said, was the use of Mexican Islamist converts to infiltrate the U.S. at the Southwest border.

A journey begins

Boles may have had his Guatemala visitor’s visa, but he would not be able to complete his trip from Moscow without a transit visa through Cuba.

This would prove to be no problem in Damascus, and he has plenty of company among Syrians, Iraqis, Jordanians, Lebanese and others passing through.

Carrying his Iraqi passport, Boles took a 15-minute cab ride to the three-story whitewashed Cuban Embassy just three blocks from the American Embassy.

Inside, friendly clerical workers handed him an application. He filled it out and handed over $70 cash with his passport and some passport-sized pictures. About a half-hour later, his passport was returned stamped, no questions asked.

Cuba’s consul in Damascus said in an interview that his country happily grants visas to any Middle Easterner who asks “because America doesn’t give anyone the opportunity to take refuge, especially after 9-11.”

“But we work another way,” said Armando Perez Suarez. “We put conditions on American people who are making war with everyone. The Arab people are the peaceful ones. We give visas to anybody who wants to visit our country.”

Suarez said he is well aware that Cuba, with its economic problems and poverty, is not anyone’s idea of a final destination.

“After that, if he wants to travel to any other country, the U.S., or Central America, this is not our problem,” Suarez said. “It’s not our burden.”

He scoffed at American concerns about terrorist infiltration.

“I’m sorry your president is from Texas,” he said. “Now you’re receiving your own medicine. The problem started in Texas and it’s finishing in Texas.”

Boles, his Cuba transit visa in hand, was almost ready to go.

Digging once more into his dwindling bundle of cash, he bought tickets from Damascus to Moscow, from Moscow to Cuba, and finally, from Cuba to Guatemala City. Total cost: $2,100. Total travel time: about two days.

He told no one of his plans, though he asked around about Guatemala and learned that lots of Arab merchants who speak his language and might be of help to him operate businesses in Guatemala City.

In June 2005, Boles packed a single suitcase, including toiletries, a sport coat and a couple of pairs of jeans.

He had a flight to catch.

Bound for Damascus International Airport, he hailed a taxi in Jaramana and bid it farewell.

END