The recent government enforcement moves against the Abid Ali Khan human smuggling network represent the latest salvo in an ongoing U.S. homeland security effort to combat jihadist border infiltration. The actions occur as a mass migration crisis at the border threatens to collapse normal border control systems and escalate this particular threat.

By Todd Bensman as originally published April 14, 2021 by the Center for Immigration Studies

As a mass-migration wave overwhelms the southern border, the Department of Justice and Department of the Treasury have brought hammers down on a Pakistan-based human smuggling organization that continues to illegally ferry foreign nationals “who pose a threat to national security” through the Americas to the U.S. southern border.

The recent government enforcement moves against the Abid Ali Khan human smuggling network represent the latest salvo in an ongoing U.S. homeland security effort to combat jihadist border infiltration (the subject of my book America’s Covert Border War). The actions against Khan also come just days after U.S. Customs and Border Protection announced two separate California apprehensions of Yemeni migrants who were already on the FBI’s terrorist watch list, one of whom also was on the No Fly list, and underscore terrorism threats perhaps exacerbated by the ongoing mass-migration crisis.

A federal indictment filed April 7 after a lengthy Miami-based ICE Homeland Security Investigations probe alleges that, since at least 2015, Abid Ali Khan has operated his network from Nowshera, Pakistan, which is known as a troubled center of violent Islamic militancy. He has often transported Afghans and Pakistanis disguised as foreign nationals of other countries.

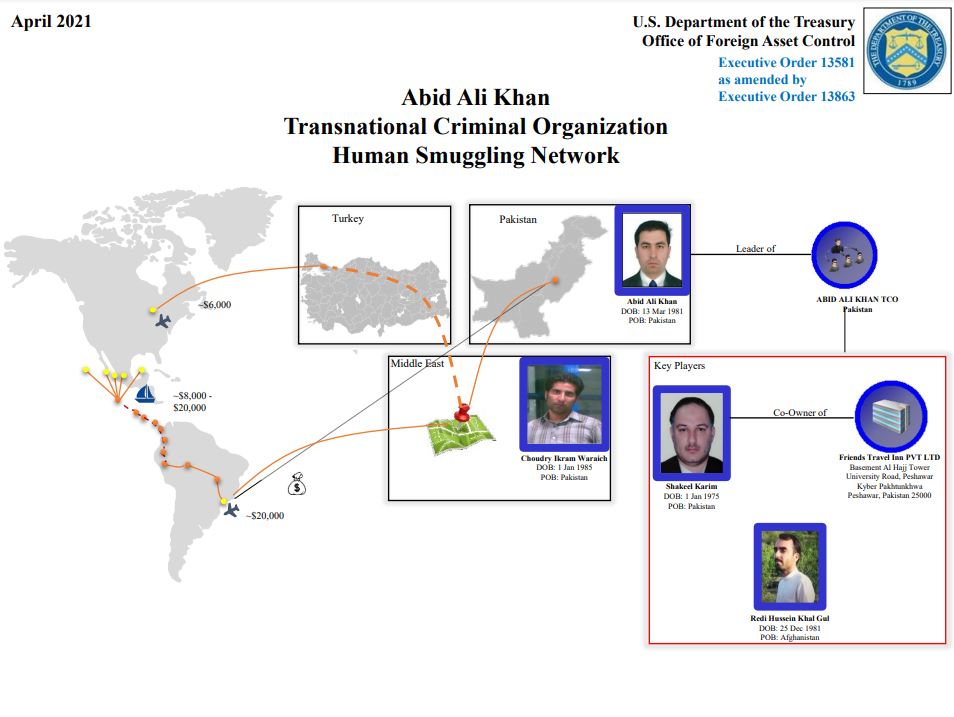

The Khan network allegedly still smuggles aspiring illegal U.S. border entrants (whom homeland security categorizes as “special interest aliens”, or SIAs) from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Brazil by air, then overland through Central America and Mexico for an average of $20,000 per person.

Neither Khan nor the key subordinates in his far-flung smuggling network apparently have been arrested. So in a rare secondary move to “help stop Khan and his network from allegedly continuing to smuggle persons to the United States”, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated Khan and three others in his network, one Afghan and two other Pakistanis, as a Transnational Criminal Organization. The designation opens the door for U.S. government operations to disrupt Khan’s finances and isolate him and his subordinates from most financial dealings. But OFAC designations are rarely, if ever, used against SIA smuggling networks like this, which stands as an indication of the danger with which U.S. homeland security views the Khan network at this early stage of the border crisis.

The involved U.S. agencies did not say where Khan or his alleged co-conspirators are today. But the U.S. actions reportedly prompted Pakistan to hunt down and question Khan in his native Pakistan. He has insisted he is not involved in smuggling, that someone based in Mexico had appropriated his name, and that he planned to march down to the local U.S. embassy with a lawyer and demand answers for why he is accused.

A National Security Threat at the U.S. Southern Border During a Mass Migration Crisis

Rarely does the U.S. homeland security establishment publicly acknowledge when suspected terrorists are smuggled over the border, although America’s Covert Border War provides extensive detail about many who have.

In a surprise departure from that tradition, however, on April 5 U.S. Customs and Border Protection issued a fairly detailed press release acknowledging the separate January and March apprehensions of two Yemenis who were already on the FBI’s terrorism watch list when they were apprehended near Calexico, Calif. CBP removed the document the next day after many on social media began citing it as evidence of a national security threat inherent in the current border crisis. CBP told CIS it had not gone through proper “review”, but did not disavow its accuracy. (An intelligence community source with direct knowledge of the cases told CIS the release was accurate.)

Announcements of U.S. government action against the Khan organization came only a day later, going largely unreported by U.S. media or, this time, even on social media. Federal officials characterized the Khan smuggling organization as a live, continuing national security threat to the United States at the southern border, albeit without the specificity of the deleted CBP press release about the Yemenis. Treasury department officials did not respond to a CIS emailed inquiry by publication time.

But Miami Homeland Security Investigations Special Agent in Charge Anthony Salisbury did note in one of the releases that the Khan network transported “people with nefarious motivations” into the United States. And while Salisbury did not elaborate, he reiterated that his Miami team was committed to prosecuting individuals like Khan who “pose a threat to national security”.

Likewise, Acting Assistant Attorney General Nicholas L. McQuaid of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, noted in the same Treasury Department statement that the government moves sought to prosecute Khan and smugglers like him “who seek to profit from … jeopardizing our national security.”

Asylum Fraud and Threats to U.S. National Security Vetting Processes

Along with the question of how many “people with nefarious motivations” Khan smuggled over the southern border is the important question of how they are able to obtain legal permission to remain once they cross. That is typically done through the U.S. asylum system, as almost all special interest aliens who enter illegally and are apprehended then claim the benefit.

As I detail extensively in the first and fourth chapters of America’s Covert Border War, SIA smugglers and Islamic terrorists who illegally entered European Union nations abused an asylum system that was structurally incapable of detecting their frauds and deceits, especially during the 2014-2018 mass-migration crisis that beset Europe. As many as 150 Islamic terrorists who illegally entered the EU over its external common land and marine borders went on to conduct terror attacks throughout Europe or were caught plotting them.

But SIA smugglers and Islamic terrorists also have exploited the highly similar U.S. asylum system’s inability to verify even the identities and stories of strangers who show up at the border with no identification or bogus passports. Like the one in Europe, the U.S. asylum process is built to give asylum claimants the benefit of the doubt and not to detect fraud or terrorism associations.

SIA smugglers often provide their clients with fake persecution stories carefully designed to get them through the initial screening processes and inside the United States with legal status that can last for many years, as I report in the book.

In line with these findings, the government alleges that the Khan organization’s counterfeit identity documents and altered stolen passports “significantly impair appropriate immigration vetting processes”, and “undermine[] the credibility of the US asylum system, damaging public confidence in the vetting process.”

Elevated Dangers During a Mass Migration Crisis

Hundreds of Pakistanis have crossed the southern border in recent years, and they are among the top 10 SIA nationalities that do so. CBP encounter statistics obtained through a CIS Freedom of Information Act request, reflecting both those who cross at established ports of entry and between them, show that 1,653 Pakistanis were encountered between 2008 and 2019. Some 175 were caught at the southern border in 2019 crossing through the brush.

Federal intelligence and law enforcement officers typically try to interview all Pakistani border-crossers to vet them for basic identity and terrorism. Officers will check pocket litter and dump cell phones and check databases looking for evidence of terrorism associations or deceit.

But the process is imperfect and vulnerable to deceit and asylum-process time constraints even in the best of times.

At issue now is that the vetting process in place for SIAs is at risk of becoming sidetracked and swamped to incapacitation during the mass migration crisis now underway. The process of learning who illegal immigrants from Pakistan and Afghanistan really are, a challenge even under ideal circumstances, enters a red zone when detention centers are overrun, Border Patrol agents are distracted by processing children, and asylum officers are hopelessly backlogged with the largely ineligible asylum claims of economic migrants from Central America.

As Europe’s catastrophe shows, those same factors can combine to become a perfect terrible storm here in the United States. These government moves against Khan hedge against that growing probability.