By Todd Bensman as published January 28, 2022 by the Center for Immigration Studies

TAPACHULA, Mexico – Beyond public light, President Joe Biden’s government has ramped up daily ICE-Air deportation flights of Haitian border crossers to the capital of Port-au-Prince, a kind of operation that brought intense criticism from the Democratic Party’s progressive liberal wing when he briefly used it to liquidate a squalid Haitian-majority camp in Del Rio, Texas last fall.

The flights petered out a month or so later. But now, while the White House has neither announced nor advertised ordering it, long-haul ICE-Air deportation flights targeting Haitians are back with a vengeance.

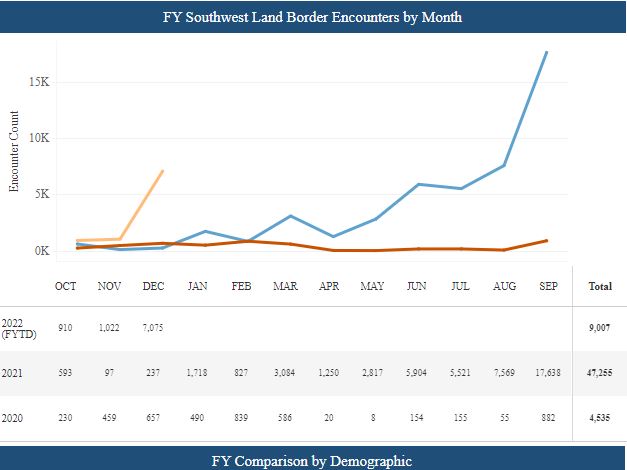

The Biden government’s quiet re-start in about mid-December coincided with a significant new spike in Haitian apprehensions at the border that month, The Biden administration’s quiet re-start in mid-December coincided with a significant new spike in Haitian apprehensions at the border that month, from 1,022 in November to 7,075 by December’s end, a public flight-tracking database and government apprehension data show. Meanwhile, Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) interviews with Haitians deep in southern Mexico show the flights once again are having the same profound impact on decision-making as when they were used to end the Del Rio camp crisis.

“Please, tell Joe Biden: Stop! Stop it! Stop the deportations to Haiti!” one Haitian man implored directly into a CIS video camera during a recent visit to this southern Mexican city near the Guatemala border. “Talk to Joe Biden, please! Stop the deportations. Help us Haitians.”

Interviews with dozens of Haitian migrants in Tapachula during a week-long visit – a three-day bus ride to Del Rio, Texas – stand as a vivid testament to the power of deportation flights to suppress illegal immigration, a metaphorical nuclear option.

Many, like a Haitian woman who gave her name as Lisette and just arrived through Guatemala after four years living in Chile, told CIS the new flights have changed their original life plans from illegally crossing the U.S. border to semi-permanent settlement in Mexico. They’ll stay in Mexico for years if necessary, or until Biden’s Department of Homeland Security once again ends the flight specter.

“It’s not possible to cross now. It’s too dangerous to enter like that,” Lisette said. “If you make it into the U.S. you don’t know how it’s going to go with immigration. That’s why we’re waiting here. For the moment, we’re trying to go legally in Mexico. We have an information group, the Haitian community here in Tapachula. Every day we’re monitoring it.”

Why Haitians and why flights now?

The new round of flights has roots in the Del Rio migrant camp crisis of September 2021. Until then, Haitians were quickly becoming one of the most prolific border-crossers of the historic American mass migration crisis, which government apprehension data shows began in earnest after the November 2020 presidential election.

The number of monthly Border Patrol apprehensions of Haitians spiked from 97 in November 2020, to 5,904 in June 2021, and then to 17,638 in September. That was the month Haitians became nationally notorious because some 15,000 of them poured over the Texas border almost overnight and created the Del Rio, Texas, migrant camp crisis, a media-spotlighted political conflagration the Biden government would not tolerate.

To most quickly extinguish it, the Biden government ramped up ICE-Air deportation flights of the Texas Haitians all the way back to Port-au-Prince. Pro-illegal immigration advocates and White House progressives found the choice repugnant, and that choice worsened a rift with security-minded pragmatists who were eying a major political liability for the upcoming mid-term national elections.

The flights, as I reported when they first began during the camp crisis, had real impact that, not coincidentally, lasted as long as the flights. Before the aircraft were mostly called back in about late October, the government had flown back some 8,500 Haitians, who used social media to warn those still en route what had happened.

While the planes were flying, scores fleeing back to Mexico told CIS that they could not accept even a marginal prospect of losing fortunes in smuggling fee money only to end up at square one.

Some Haitians found this prospective financial loss so loathsome that they revolted and destroyed the interiors of the first aircrafts (photos of which CIS has reviewed). Others still in Texas receiving the news in online chat rooms seized control of several ICE buses that were taking them to airports. What happened for a while after that? The Haitians kept coming to Mexico by the thousands but kept their distance from the border, their apprehension numbers plummeting by 95 percent as CIS’s Art Arthur explained.

But then the flights mostly ended along with media interest in Haitians.

The plummet was temporary, because the flights were all but halted.

In December, the Biden DHS could not have missed that the number of apprehended Haitians was skyrocketing again, in what turned out to be a 600 percent increase by month’s end.

Had national news reporters at President Biden’s most recent press conference asked a single question about the border crisis, they might have learned the administration had just turned on the controversial Haitian deportation flights again.

Did these signal the triumph of more border-hawkish White House pragmatists over Biden’s progressive-left immigration advisers? We don’t know but two key senior immigration advisers from the latter camp – Esther Olavarria and Tyler Moran – resigned just weeks after Biden ordered the flights resumed.

The specter returns

Indeed, the flights are hauling Haitians from Texas to their home country almost every day now, according to flight tracking data for a number of known ICE-Air chartered jets that appear to have amped up on or about December 13, 2021.

Take the ICE-chartered World Atlantic Airlines MD-83 plane named “Jackie,” which can carry 172 passengers. According to the Flightradar24 database, on December 13, the Jackie logged the first of what has become a continuous series of flights either from the McAllen or Laredo, Texas airports to Port-au-Prince, 26 in all through to January 25. Other ICE-Air subcontractor aircraft are flying, too, though not all of them are known.

The ICE-contracted iAero Airways aircraft N627SW, for example, flew four flights in early November from Laredo to Port-au-Prince or Cap-Hatien, but then flew 11 from December 14 through January 20, a clear tempo increase. Another IAero Airways flight flew a first flight from Miami on January 18. Other chartered airlines are likely flying to Haiti as well, but DHS has not released data on its repatriation flights, nor could any public affairs announcements be found.The anti-immigration enforcement group Witness at the Border, which deplores air deportations as “death flights,” noted in a January 3 report that: “A deep declining trend in return flights to Haiti was reversed in December,” with an estimated 2,750 Haitians returned in just the last two weeks of that month.

Impact on Haitian decisions to cross

Even if the American public is unaware of them, these operations occupy the forefront of minds among Haitians in Tapachula during the week of January 13-21.

Haitian national Nixon Deleonne, a single unmarried man, typifies how the deportation flights are playing. He spent $2,500 in savings and borrowed money on smuggling to get from Brazil, where he’d been living for three years, to Tapachula. His eye was on the American dream and “a better life” than what Brazil could offer but now he keeps hearing about the deportation flights.

“If Jesus give me a chance to cross the border of the United States, I would thank God because after two years, four years, I can build my house. I can do something. Brazil is good but you can’t find the money to raise your family. The United States is the place everybody in the world wants to go there. It’s better than all of the countries. You have a good salary and good security.”

At the moment, the Mexican government was restricting freedom for migrants to move beyond Tapachula until they secured Mexican asylum, residence cards or visas. Most use these to make a beeline for the U.S. border three days away. In December, after some 50,000 migrants backed up in Tapachula, the Mexican government relented and let 50,000 move forward with a new document called a QR Code visa, just to clear them out, as CIS has reported.

But Deleonne arrived in Tapachula too late for that. Even if he gets that QR Code visa break or his regular documents in a month or three, he said he will not cross the American border because of the deportation risk he and all the Haitians in town talk about constantly.

The new plan?

“I’m going to see what they’re doing [the Americans]. If they continue to make some deportation, I’m not going to cross the border. If I hear they stop, I will try to get my chance. I don’t want to go back. I don’t have any problem staying here for one year, two years, three years. In my mind, I say one of these days, I’m going to cross the border. That’s my destination, my objective, to one day cross the border.”