BROWNSVILLE — The human smuggler offering to help Aamr Bahnan Boles and his two friends cross the border into America was tall, dark and pricey.

“I can get you to Texas, no problem,” he told them. “For a thousand dollars each.”

Boles and the others had just walked out of the detention center for immigrants in Mexico City. The guards, knowing the three were about to be freed after three months in custody, had arranged the rendezvous with a smuggler.

Boles would recall later how the smuggler — in street parlance a coyote, or someone who makes a living helping undocumented immigrants cross the border — was leaning against a tractor-trailer rig outside the jail gates.

He said his name was Antonio.

“Where are you from and where do you want to go?” the smuggler asked.

“We are Iraqis,” Boles said in halting Spanish, “and we want to go to America.”

Boles, a Chaldean Christian determined to escape the Iraq war, is categorized by the U.S. government as a “special-interest alien,” those from 43 countries where terror groups are known to operate. As such, they can be subjected to extra screening and harsher treatment than other immigrants when caught crossing illegally.

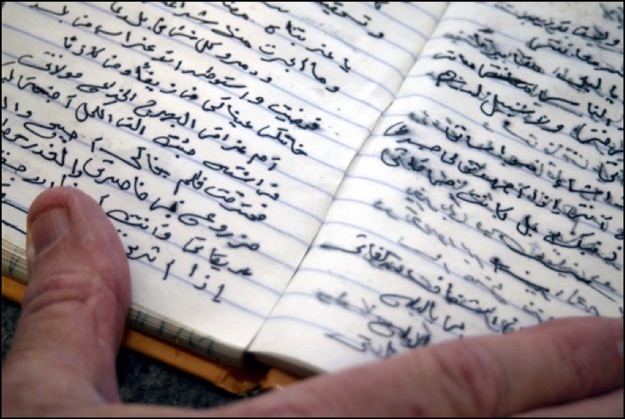

terror. This diary was discovered at the border in Arizona, sparking a frantic FBI investigation that soon determined that the author was a love-struck Iranian who’d just left a Mexican woman behind to seek his

fortune in America. Photo courtesy of Bill Hess, Sierra Vista Herald.

Near the end of his journey to America — born in the shadows of a Damascus, Syria, restaurant and culminating nearly a year later with the final push into Texas — Boles ran smack into this post-9-11 security net.

But the system is fallible, and just as likely to punish the benevolent as to release the dangerous.

On the U.S. side, authorities are feeling their way sometimes blind and scared. Once over the Texas border, Boles would encounter various jail cells, a skeptical magistrate, a distrusting government lawyer and a bizarre courtroom quiz about his biblical knowledge where his very freedom hinged on the right answers.

Boles managed to cling to his last couple thousand dollars after Mexican immigration agents plucked him off a bus from Guatemala, where he had arrived eight months earlier after an air trip from Damascus to Moscow and through Cuba. His new traveling companions, Ammar Habib Zaya and Remon Manssor Piuz, also had money.

Zaya and Piuz, like Boles and many Iraqis caught traveling through Mexico, said they were members of a Christian minority who had fled their homes in Iraq after Islamic extremists began killing and kidnapping men in their community. Zaya said he had worked on an American military base in Iraq, doing laundry for the troops.

The United States was giving few visas to Iraqi refugees, so they’d struck out for America and were caught by Mexican immigration. Mexican and U.S. intelligence agents interviewed them in custody as part of a secret counterterrorism program aimed at capturing immigrants from places such as the Middle East.

While other Middle Easterners who provoke some level of suspicion get deported to their homelands, Boles and his two new friends eventually were released with papers ordering them to either leave the country or apply for Mexican residency within two weeks.

The choice was clear.

It made sense that the three young men would band together for the final leg of their journey. There was safety in numbers, but they also had much in common. They were from the same Iraqi province of Mosul and all in their early to mid-20s. All had fled the war.

In the Mexican jail, Zaya and Piuz incorrectly told Boles about a surefire way to get legal status after they crossed into America. All they’d have to do was plant their feet on U.S. soil, find a government representative and claim political asylum. The Americans would have to give them a fair hearing on claims of religious persecution in Iraq, and maybe they could get permanent residency and a path to citizenship.

Before the end of their first day of freedom in Mexico, Boles and his compatriots sat crowded together in the sleeper compartment of Antonio’s tractor-trailer cab. The truck was barreling northeast from Mexico City toward the northern industrial city of Monterrey, nearly 600 miles away.

In Monterrey, the men transferred with Antonio to a different truck, this one bound for Matamoros, another 200 miles north and just across the border from Brownsville.

Nearly a full year after flying out of Damascus, Boles was almost to his goal now.

His excitement and apprehension grew.

In Matamoros, Antonio handed the travelers over to another man. They were driven by car over dirt roads that wound through farmland and came to a stop a half-mile from the Rio Grande. It still was dark. Boles and his two companions followed the coyote over dirt trails.

The smuggler told them not to talk; Border Patrol agents could be just over the other side. They stripped to their shoes, bundled their clothes and shuffled down the riverbank to the neck-deep, fast-moving green water of the Rio Grande. At 5:20 a.m. April 29, 2006, they waded across to Texas one at a time using an inner tube.

The men scrambled back into their clothes. They were about 6 miles east of the rural town of Los Indios.

“America!” Boles thought as he faced towering sugar cane fields. “I’m finally here. I’ve made it to America.”

His joy would be short-lived.

Boles’ small group triggered a motion detector while hiking up a dirt road toward U.S. 281. U.S. Border Patrol agents in three SUVs rumbled out of their hiding places to check the area.

Boles and his companions were hiding in brush when they saw the green and white vehicles coming toward them. They leapt out with hands raised and ran toward what they thought was salvation.

“Iraqi Christians! Iraqi Christians! Iraqi Christians!” they shouted over and over, jumping up and down. “Political asylum! Political asylum!”

None of them could have known they already were marked men.

A flawed system

Federal agents from Texas to California and from Maine to Washington go on red alert whenever a special-interest immigrant gets caught crossing the border — or at least they are supposed to.

The goal is to put everyone captured, regardless of nationality, into deportation proceedings or immediately send them back. The routine is to run the fingerprints and names of apprehended border crossers through interlocking government databases that look for criminal history, outstanding warrants or past immigration violations.

But apprehensions of border jumpers hailing from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia trigger under-the-radar procedures that go well beyond these first rudimentary checks.

Border Patrol agents are supposed to run these names through the agency’s National Targeting Center database, which looks for any link to terrorism or flags when other agencies have an investigative interest in the name.

The next step is to notify the nearest FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force, which has its own more extensive databases and access to counterterrorism and intelligence resources. The Border Patrol has logged hundreds of such referrals to the FBI each year since 9-11.

Border Patrol agents made 644 referrals in 2004, 647 in 2005 and 563 in 2006, according to agency data requested by the San Antonio Express-News. If sufficient suspicions are aroused, the FBI can place a national security “hold” on an immigrant to keep him in custody while agents investigate further.

FBI Special Agent in Charge Ralph Diaz, who oversees bureau activities in South Texas from his San Antonio headquarters, said an effort then is made to interview every special-interest immigrant in person.

“They’re not all necessarily a threat,” Diaz said. “But we don’t have the luxury of presuming that. The flag goes up and we say, ‘Let’s take a look at this.'”

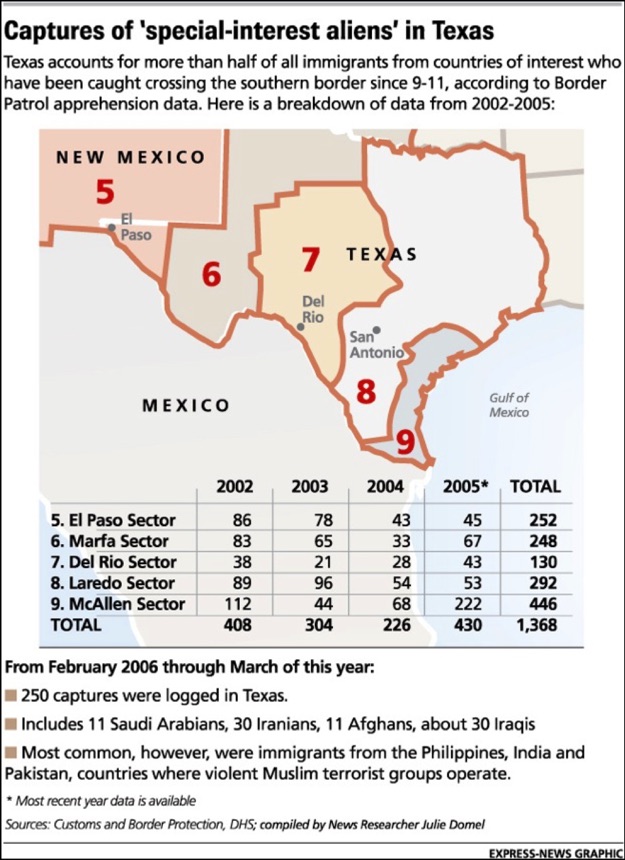

The workload is not insubstantial. More than 1,500 special-interest immigrants have been captured in Texas since 9-11, including nearly 300 between March 2006 and April, among them Boles and his two companions, along with Iranians, Yemenis and Afghans. Diaz and other FBI officials familiar with special-interest immigrant assessments said the vast majority are determined to be economic refugees or people fleeing wars and political persecution.

“It’s not reached a level where we’ve had a threat to national security in the San Antonio district,” said Diaz, who has been on the job about a year.

Other federal counterterrorism authorities, however, say they have connected some border jumpers to terrorism. Among them was a South African woman of Middle Eastern descent whose July 2004 arrest at the McAllen airport with wet clothes, thousands in cash and a mutilated passport made international headlines.

Farida Goolam Ahmed eventually was charged with a simple illegal entry offense and quietly deported, but key documents remain sealed. A Dec. 9, 2004, U.S. Border and Transportation Security intelligence summary, accidentally released on the Internet, states that Ahmed was “linked to specific terrorist activities.”

Government officials familiar with the case now confirm Ahmed was a smuggler based in Johannesburg, South Africa, who specialized in moving special-interest immigrants into the United States along a United Arab Emirates-London-Mexico City-McAllen pipeline.

Houston-based federal prosecutor Abe Martinez, chief of the Southern District of Texas national security section in the U.S. attorney’s office, was asked if Ahmed or anyone she smuggled might have been involved in terrorism.

“Were they linked to any terrorism organizations?” Martinez said. “I would have to say yes.”

Martinez and a number of Texas-based FBI officials declined to elaborate. But an August 2004 report that appeared in the Washington-based Homeland Security Today quoted several unnamed government counterterrorism officials as saying Ahmed also was found to be ferrying “instructions” from a Mexico al-Qaida cell to another cell in New York.

The article reported Ahmed’s arrest led the CIA to capture two al-Qaida members in Mexico and several Pakistani al-Qaida members in Pakistan and in Britain who all were part of the plot to attack targets in New York.

The Express-News couldn’t independently corroborate the Homeland Security Today report.

Other immigrants who have prompted some level of uncertainty or suspicion end up deported to their home countries.

Kyle Brown, an immigration attorney in McAllen, said two Afghans he represented had their asylum applications denied and were deported after the FBI discovered “a series of telephone numbers” in their possession.

“One of them (telephone numbers) led back to a link to terrorism,” Brown said.

But FBI officials, including San Antonio’s Diaz, acknowledge the bureau’s current system of assessing whether someone is a terrorist is far from error-free.

Often, immigrants show up with no documents or with fakes. FBI agents could have little to run through terror watch list databases, or, when a name is real, it might not be entered.

“You interview them, run every database possible, fingerprints, watch lists, check their stories. You get some sort of a feel of their sophistication,” said an FBI official who works along the Southwest border. “Could we be fooled? Of course.”

Last year, a Homeland Security Department audit cited weaknesses in the government’s ability to differentiate between persecuted political asylum seekers and terrorists.

“The effectiveness of these background checks is uncertain due to the difficulty verifying the identity, country of origin, terrorist or criminal affiliation of aliens in general,” the audit report stated. “Therefore, the release of these (migrants) poses particular risks.”

FBI and Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents concede they can’t get around to interviewing every captured special-interest immigrant. Until thousands of new detention beds were ready last year, Border Patrol and ICE routinely released special-interest immigrants on their own recognizance, usually never to reappear, simply because there was nowhere to keep them.

New detention space lets the government hold more undocumented immigrants for deportation proceedings. But even then, some are let go and not fully investigated, according to a review of hundreds of intelligence summary reports showing law enforcement activity along the Texas-Mexico border.

The reports suggest the FBI is not always getting referrals, and full investigations aren’t being conducted.

One of many such examples occurred Dec. 1, according to an intelligence summary report from that day. “Sudanese detained at Carrizo Springs station. Released.” The State Department lists Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism.

Three days later, agents picked up a Pakistani at a checkpoint in Val Verde. “No derogatory,” the report stated, referring to a watch-list check. “Released.” Two days after that, Border Patrol agents picked up an Iraqi and had a watch-list check run on his name, too. “No derogatory info. Released.”

Sometimes Border Patrol agents exercise a new authority provided by Congress to simply expel undocumented immigrants back to Mexico without court oversight, a process known as “expedited removal.”

While helping to reduce congestion in detention centers and courtrooms, expedited removal also loses opportunities to investigate the immigrants and their smugglers.

In a typical such instance, on June 20, Border Patrol agents arrested an Eritrean national in McAllen.

“Subject stated that he flew from Sudan to Mexico City using a photo-substituted French passport,” the report stated. “He was processed for expedited removal.”

The Lord’s Prayer

To American agents, Boles and his two fellow Iraqi travelers were big question marks. Like many special-interest immigrants, they were captured with no identification or documents, just a story about being persecuted Christians in need of safe harbor. Their inability to back their story with evidence — even to prove the validity of their given names — would bode ill.

Border Patrol officers who caught Boles transported him to one of their facilities in Brownsville, where his name once again was run through the databases. Those checks came out clean. The FBI was notified that Iraqis had been caught at the river. But still no one could say for sure who they were.

Before Boles’ first day in American custody was over, immigration authorities in Brownsville charged him and his two compatriots with the federal misdemeanor of illegal entry, which carries a maximum punishment of six months in prison.

Boles’ appointed attorney, Humberto Yzaguirre Jr., recalls assuring his three clients that the charge was routine and they would serve no time. They would plead guilty, be given time served and then get out on bond to pursue political asylum claims — assuming the FBI quickly cleared them.

Yzaguirre had seen it happen this way a thousand times, he told them.

But it wasn’t to be.

No one in the Brownsville federal court system was ready to believe that Boles, Zaya and Piuz were Christians.

All three Iraqis had pleaded guilty and were awaiting their sentencing before U.S. Magistrate Court Judge Felix Recio, scheduled for May 5, 2006.

In the meantime, the court had ordered probation officers to interview the three Iraqis to collect their stories and make recommendations to the judge.

Attorney Paul Hajjar, a Lebanese American hired as a defense interpreter for the proceedings, recalled overhearing the Iraqis talking among themselves in a dialect that was not Arabic. He recognized it as a contemporary derivative of the ancient Aramaic language dating to the days of Jesus Christ. It is spoken only by Middle East Christians.

Hajjar asked Piuz about the language. Just then, the Iraqi broke out with a heartfelt rendition of the Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic, loudly enough for all to hear.

Piuz closed his eyes as he continued slowly, bowed his head and spoke the words of the prayer with what appeared to be deeply felt angst, Yzaguirre recalled, as though he hoped God could help him out of the situation. When he finished, Hajjar turned to the probation officers. These men, he said, could not be Muslims.

“See? They are exactly who they say they are,” he said. “I don’t see Muslims saying the Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic. A Muslim wouldn’t speak Aramaic to begin with, and they certainly wouldn’t know the Lord’s Prayer.”

The display wouldn’t help the group. It wasn’t included in the report that would go to the judge. And the FBI still hadn’t shown up.

Taking no chances

Magistrate Judge Recio already had decided he wasn’t taking any chances with Iraqis.

“Mr. Boles,” the judge said at their sentencing hearing, “good morning. Do you have anything you wish to say to the court?”

“No,” Boles replied in Arabic, then added, “If you could just give us some consideration.”

“Mr. Piuz, do you have anything you want to say to the court?”

Meekly, Piuz replied, “Just, if you could take care of us.”

Next, Recio asked Yzaguirre the same thing. Yzaguirre assured the judge that no evidence had surfaced indicating that his clients were Muslims instead of Christians.

The judge then turned to the government’s prosecutor, Assistant U.S. Attorney Dan Marposon, for his opinion.

Marposon, who has declined several interview requests, said he concurred with the pre-sentence report’s recommendation of minimal punishment, the usual time served.

But Recio, who didn’t respond to three interview requests for this report, was about to surprise the government’s prosecutor and everyone else in his courtroom.

“We know that this country is in war in Iraq,” he said. “We know the problems associated with all of that, and it gives reason for this court to be cautious and to take things into consideration carefully and to apply the law to them as carefully as possible.”

Recio went on to express skepticism about the Iraqis’ stated motives for coming to the United States when they could have stayed in Europe or gone elsewhere much more easily. He said he doubted their story that they’d all met for the first time in Mexico when the three men came from the same province.

“It would be highly unlikely that if you’re released from any Mexican prison that you would be released with any money whatsoever,” the judge said. “So someone is financing you, or you’re receiving funds from someplace. We have no idea where those funds are coming from.”

The judge reserved special ire for the government.

“I might add the government has been very lax in coming forth with any evidence to either support or go against the claims of these individuals,” he said. “Who did they check? What did they check? What did they verify? Who did they talk to? I don’t know.”

Recio sentenced them to six months in prison.

“We want to promote respect for the law. We want to protect the public from further crimes, and we want to provide a deterrence for other criminal conduct,” he said.

The gavel came down with a crack.

The hearing had lasted 15 minutes.

Boles, Piuz and Zaya were devastated. The U.S. marshals handcuffed them and led them away to prison.

Tougher grilling

About a week later, the FBI showed up. The experience would not be pleasant.

Two men from the bureau, an ICE agent and a Lebanese interpreter arrived at the jail where the prisoners were being held.

Boles found their questions insulting and their manner brusque and intimidating, unlike his experience with the Americans who had questioned him in Mexico.

The agents, he later recounted, demanded to know why he had come to America, and the names of the smugglers who brought him.

They began asking personal questions, like if he had sampled tequila while in Mexico and what it had felt like, knowing that practicing Muslims who don’t drink alcohol wouldn’t have an answer.

Agents demanded to know about his military experience. Boles believed his three-month incarceration in Mexico was the result of admitting he’d been a conscript in Saddam Hussein’s army. So he lied this time.

“No, I never served in the military,” Boles told the agents.

But the agents had his statements from Mexico. They pounced, hoping to break down a possible cover story.

“Don’t you think we know what you said in Mexico? You’re a liar!”

For the next five hours, they grilled Boles.

They threatened to charge him with lying to federal law enforcement officers, a felony that could bring a five-year sentence, unless he told them who he really was and what he was doing sneaking into America.

They threatened to send him back and force him to join the new Iraqi army, where he would probably suffer a violent death.

At last, the agents left Boles, exhausted and feeling hostile toward the country he hoped would adopt him.

New agents would return three weeks later and interview him again about the details of his life and travels, most likely looking for inconsistencies.

That was the last he heard from the FBI and ICE.

Mixed-up feelings

Boles spent his 26th birthday behind bars.

After he completed his sentence in November 2006, he was remanded to the custody of immigration authorities and transferred to a federal detention facility near Port Isabel. Once again, Pakistanis, Jordanians and Yemenis were among his cellmates.

Most immigrants in similar situations probably would be deported at this point or be eligible to pay a bond and be freed while pursuing a political asylum claim. But the FBI still had not cleared Boles, and until it did he would remain in limbo.

Relatives in Detroit hired Harlingen immigration lawyer Thelma Garcia, and she began pushing government lawyers to secure a ruling from the FBI. Finally, toward the end of the year, the FBI notified the court that it had cleared Boles. He was not a national security risk.

But suspicion can be hard to overcome in Texas, at least when it comes to Iraqis during a war. There was still no proof of his Christian identity and his story of persecution at the hands of Muslims.

Boles would be asked one last time to prove his credibility with a test of his religious faith.

Garcia quickly moved to get a hearing date that would allow Boles to bond out and go to Detroit.

U.S. Immigration Judge William C. Peterson presided over the hearing Jan. 3. The government’s lawyer was Assistant Chief Counsel Sean Clancy.

Clancy, who some people think resembles actor Randy Quaid, is a classic Irishman. He has fair features and reddish hair. He wore a crisp suit.

Clancy put Boles through his final test, opening with a battery of questions designed to ascertain, finally, whether he was who he said he was. Garcia’s notes from the proceeding chronicle this unusual courtroom exchange:

“What’s a Christian?” the prosecutor asked.

Clancy was assertive without being confrontational.

“We believe in Jesus as our savior and we believe in God,” Boles replied.

Clancy seemed to accept the answer, Garcia thought.

“Who is Jesus and where did he come from?” Clancy asked Boles.

“He is the son of God, son of Joseph and the son of David.”

“Was he just another man?”

“No, he was the son of God.”

“How often do you pray?”

“I pray every Sunday, three times a day.”

“What do you do on Sunday?

“I go to morning Mass.”

“What’s Mass?”

“We pray with a Bible.”

“What’s Communion?”

“We take the body of Jesus Christ.”

“In what form do you take Communion?”

“Bread. Wafers. The priest prays over it and then we eat it.”

Clancy turned to the judge.

“That’s all I have,” he said. “It’s up to the court, your honor.”

Peterson set Boles’ bond at $1,500. Relatives paid it a couple days later and then wired money for bus fare to his lawyer in Harlingen. It was enough for a one-way trip to Detroit aboard a Greyhound.

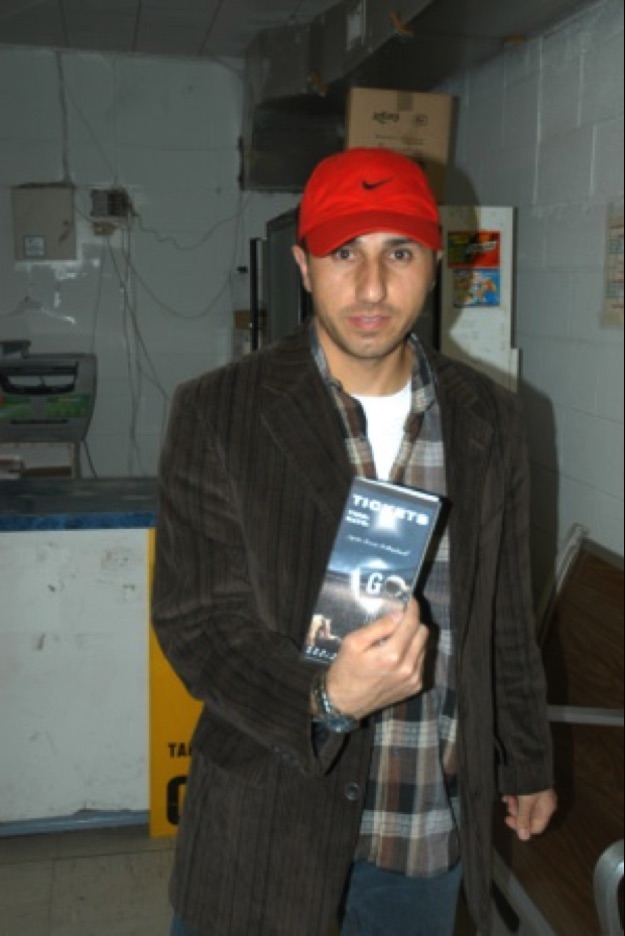

The next night, on Jan. 6, a Border Patrol agent drove Boles to a bus station in Brownsville and let him off at 11 p.m. with all of his worldly possessions: a bag filled with a few basic toiletries, extra socks and underwear and some documents. He wore a red Nike baseball cap, a brown corduroy sport coat and a grim expression.

Boles felt bitter. He did not think the FBI and the U.S. judicial system had treated him well.

But he was ready to get on with his new life.

“My feelings about America are all mixed up,” he said as he ate his first American meal as a free man, a cheeseburger and fries at the Brownsville Cafe. “We knew they’d do an investigation of us, but why did it have to be a criminal investigation? I believe it was an unfair sentence for him to send us to jail.”

But Boles, who had not had much to laugh about in a long time, couldn’t contain his dry sense of humor.

Casting a sideways glance, he said with the measured delivery of a standup comic:

“I know they have to protect your country.

“But why take so long to do it?”

The long journey of Aamr Bahnan Boles from Iraq had consumed almost three years of his life. Along the way, some of his enthusiasm had been lost, the joy of second chances tempered, the burden of freedom, loneliness of secrecy and imperfections of America all driven home.

“I feel lost,” he said. “It’s the first time I’ve been free.”

Boles probably will remain free, though his claim for political asylum continues wending its way through the system. Returning to a Texas courtroom, which Boles must do in August, needn’t worry him, said Martinez, the prosecutor who oversaw the FBI’s handling of Boles.

“His story,” Martinez said, “is true.”

On a Saturday morning in January, that story, a refugee’s story, entered its final chapter as Boles stepped onto a Greyhound bus in Brownsville. It took him north through Harlingen into the vast expanse of Texas and then into America’s heartland.

Forty-four hours and many stops later, the odyssey from Damascus to Detroit ended at another Greyhound depot, and Boles began a new life.