By Todd Bensman as published June 8, 2023 by the Center for Immigration Studies

AUSTIN, Texas – In the latest in his series of state-level immigration-control initiatives, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has okayed an unusual new tool: a floating marine barrier to be deployed in the Rio Grande, three sources with direct knowledge confirmed to the Center for Immigration Studies.

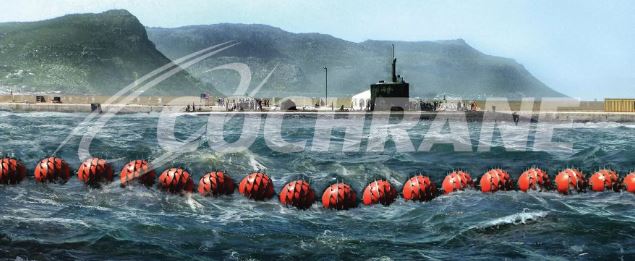

The first 1,000 feet of floating barrier, consisting of large rotating buoys strung tightly together on thick steel cable, will be rolled out on a highly trafficked stretch of the Rio Grande between Piedras Negras, Mexico, and Eagle Pass, Texas, where a rising torrent of immigrant family groups have been crossing to turn themselves in since the end of Title 42 pandemic instant expulsions May 12, the sources said. Immigrants would have difficulty crossing over the buoys because they would rotate backward toward immigrants attempting to climb over them.

Texas has already purchased lengths of barrier from Cochrane, a corporation that specializes in marine barriers most often for navies. Texas will deploy its first thousand feet in June or early July, two sources said.

If it proves effective, Texas will roll out more in immigration hot spots on the Rio Grande.

Such a move comes with some political risk as physical barriers to illegal immigration such as high walls reliably draw criticism and controversy from illegal immigration advocates – and hostile media attention if immigrants are injured attempting to defeat them.

State officials are aware that some immigrants will try to swim under the barrier.

“The whole design is to block the thousands, not the one” who might defeat it, one state official said.

But internal discussions are underway as to whether to use underwater webbing that would hang some distance beneath the barrier to deter such attempts on grounds that these might reduce, rather than increase, the chances of drownings.

The idea comes as part of a broader new Texas initiative where Abbott has deployed state police and national guard troops, bolstered by forces coming from more than a dozen other states, to physically block immigrants from leaving the water or riverbank. These forces, some armed with pepper-ball air guns, guard from behind coils of razor wire that Texas has strung for miles along popular river crossing spots.

In May, Gov. Abbott decided to double down on the essentially ad hoc tactic after it proved decisively successful in halting a massive surge of thousands of immigrants who were crossing in the Matamoros/Brownsville area.

But elsewhere, marshes, islands, and heavy brush in other crossing hotspots like the Piedras Negras/Eagle Pass region have presented more physical challenges to the state’s river-blocking tactic.

The marine barrier would be laid out in the middle of the Rio Grande in areas like these, where the actual international border runs between the two countries, providing state forces more time to muster and respond when swimmers start arriving at the barrier or defeating it.

The plan also comes at an auspicious time in the most voluminous mass migration crisis in American history, now it in its third year. After the pandemic-era Title 42 rapid expulsion measure ended on May 11, Texas has seen increasing flows of family groups, as I reported in the New York Post. They have discovered that the Biden administration is not enforcing the threatened punishments like quick expulsions and prosecution for immigrants who cross illegally instead of waiting in Mexico for a fast-pass U.S. entry permit via the CBP One cell phone app.

Family groups in growing numbers are now deciding to abandon the CBP One appointment process, which entitles recipients to cross “legally” but involve a long wait to get an appointment. This is because they’ve discovered that the administration is just releasing them when they cross illegally, allowing them to get in to the U.S. more quickly.

This discovery has resulted in increasing numbers of crossers in the Piedras Negras/Eagle Pass area, as well as elsewhere along the 1,200-mile Texas border, presenting a challenge for Abbott and the states that have joined him in deterring these powerfully enticed flows.