An ISIS franchise in the Democratic Republic of Congo and rampaging militias engaged in massacres, kidnapping, and torture warrants enhanced vetting of hundreds of Congolese young men crossing the U.S. southern border. Government must pause from the chaos of the Central American influx and ensure that migrants from Central Africa are not as quickly released into the interior. Greater vetting efforts with this population can clear Congolese migrants for asylum while also serving a duty to protect the population in which they will soon settle.

By Todd Bensman as originally published by the Center for Immigration Studies on June 20, 2019

Asylum seekers from Central African countries are pouring over the U.S. southern border these days in unprecedented numbers, crowding into bus stations like the one in downtown San Antonio for trips to future permanent homes all over the United States.

Claims for political asylum by citizens of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Republic of Congo (ROC), since there is real war and persecution in those nations, may have more merit than do similar claims by the city-sized numbers of Hondurans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans who are mainly economic migrants ineligible for asylum.

But with the Central Africans showing up, homeland security personnel at the border and decision-makers in Washington, D.C., must keep in mind two intertwining factors about these migrants that justify heightened vigilance and an immediate security screening regimen that I’m told is not happening as Central African migrants are released into the U.S. interior.

The first factor is that many thousands of murderous, warring militia members have rampaged for years through villages of Central African nations like the Democratic Republic of Congo on killing, raping, kidnapping, and looting sprees. Their atrocities and massacres in the eastern part of that country are the stuff of horror films and, hopefully, future international war crimes tribunals in The Hague.

Militia-backed tribalism aside, just this past April, the Islamic State claimed its first attack in the DRC, in which eight government soldiers were killed.

ISIS is now referring to the DRC as the “Central Africa Province of the Caliphate”. But jihad-inspired murder is not new in the DRC.

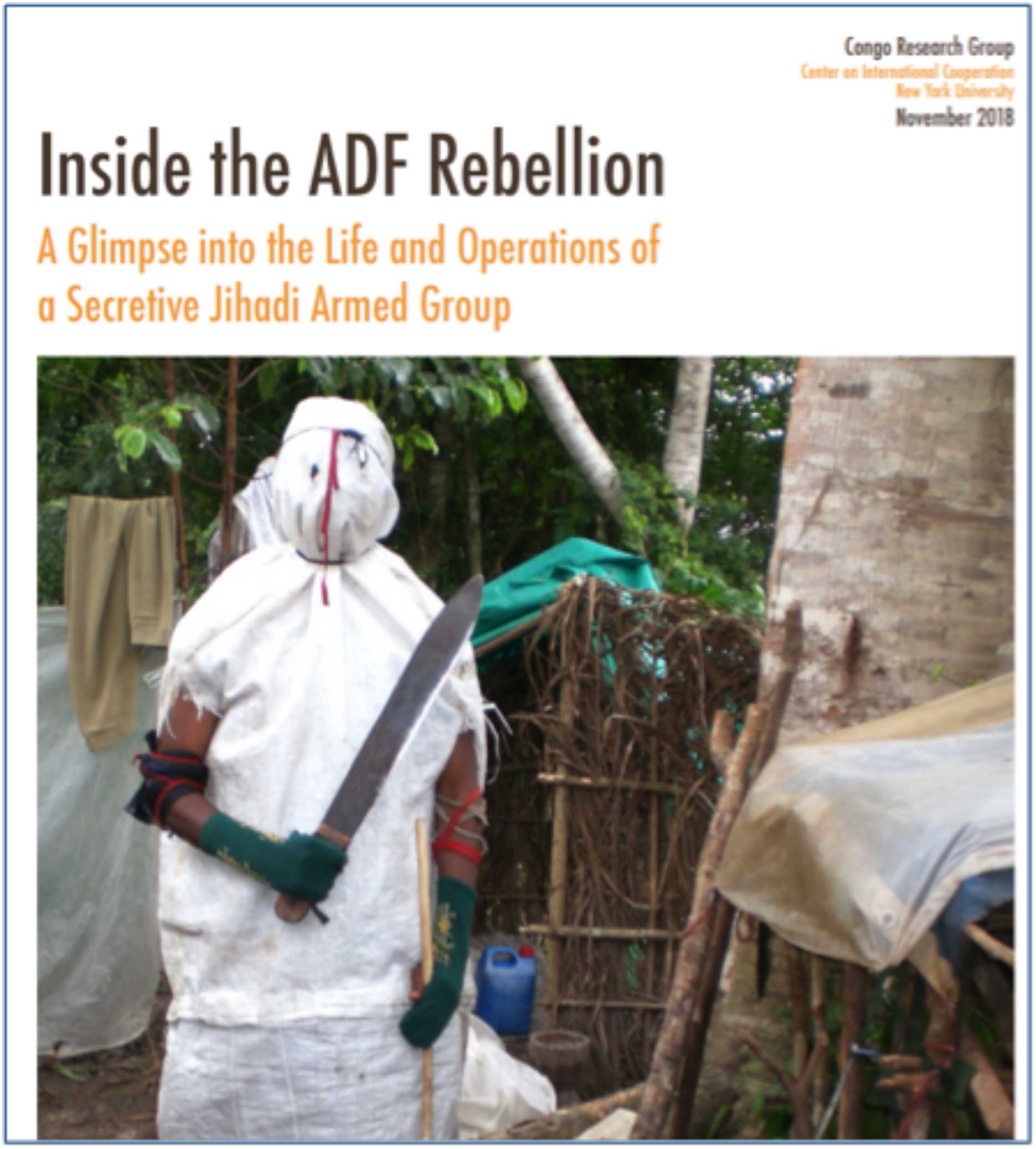

The Congo Research Group issued a report in November 2018 documenting the increasing spread of Islamist jihadist ideology among some groups and allied militias, particularly in eastern DRC, that seems very much akin to ISIS ideology. Much of this trend seems to have seeding in the Ugandan Allied Democratic Forces, a particularly brutal militia with operations throughout the DRC’s east that is rebranding itself as an ISIS franchise and whose members are now largely composed of converts to Islam. Thousands of violent militia fighters have been sprung in mass prison breaks recently.

Heavily armed Islamists have killed and wounded dozens of United Nations peacekeepers in recent years, including one 2017 attack that UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres called “a war crime”.

The second factor that must be considered with regard to the Central Africans moving over the U.S. southern border is that too many arrive with no identification and almost entirely unverifiable personal histories, since actual basic governance that would include maintenance of criminal records and intelligence databases is limited for embattled, truncated, and generally incapable governments of these countries.

Our inability to learn much about the backgrounds of incoming migrants who just show up and claim asylum, and the prevalence of horrific criminality among many different militia groups whose numbers run to tens of thousands, to include government defense forces, combine to create a unique security vulnerability for America.

It is fair and right to put migrants from Central Africa through enhanced vetting processes that would not be necessary for most Central Americans.

It’s too early to know how many Congolese are on their way, but judging from photos and news video of those who have arrived, many are young men of military age. An acquaintance working as a volunteer nurse practitioner in Panama emailed photos to me this week from a government migrant camp in Darien Province, which I visited in December 2018 and where I observed maybe a few dozen Congolese on their way north from Colombia. The nurse said thousands were in the same camp now and that Panamanian government sources told her 35,000 more Africans were on their way in through the Darien jungle toward America’s border right now.

In fairness, many of the Central Africans who have already arrived and who are going to be arriving soon, some with young children, may well have been victims of these militias and the fear and insecurity they have wrought. Hundreds of thousands of citizens have fled the bloodshed. Millions have died in warfare in the Democratic Republic of Congo dating to the 1990s in successions of violent spasms of warfare.

But so too must U.S. homeland security authorities ensure that none of its fleeing citizenry were active participants in the killing and are now hiding among their victims and gaming our asylum system to evade justice, or perhaps to one day commit violent acts in American cities for ISIS.

Europe stands as an emblematic case study that these things can and do happen. ISIS war criminals and terrorists were among the two million migrants that overwhelmed the European Union’s external borders from 2014-2017. Dozens of ISIS war criminals who posed as asylum-seeking war refugees have been arrested and charged with their atrocities while others went on to plot and commit new ones in a half-dozen European nations.

A recent New York Times report about the Congolese said their arrival at America’s southern border “has surprised and puzzled immigration authorities and overwhelmed local officials and nonprofit groups.”

Surprise and puzzlement is not a good place for the Department of Homeland Security to be.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection must pause from the chaos of the Central American influx and ensure that migrants from Central Africa are not as quickly released into the interior — just to free up bed space in facilities. Instead, bed space should be specially reserved for them so that ICE intelligence, law enforcement agencies, and even the FBI, can conduct in-depth security interviews with Congolese migrants, inspect their pocket trash, take the data from any cell phones, and file detailed reports for the asylum processes to come.

Greater vetting efforts with this population will do a service to Congolese migrants, by clearing them for asylum while also serving a duty to protect the population in which they will soon settle.