By Todd Bensman as published April 4, 2024 by The Daily Mail

‘Hit the gas!’ I barked at my translator behind the wheel of our tiny rental car.

‘Let’s get the f*** out of here!’

We tore off – and left the reflections of two cartel men shrinking in our rearview mirror.

Reporting on the ground in northern Mexico comes with certain risks and chief among them is unexpectedly coming face-to-face with gunmen.

I’d come to La Linea Cartel territory, a vast high desert region west of Ciudad Juárez, to document a part of the migrant crisis that few ever see: the smuggling of dangerous criminals into America.

Juárez is a crime-ravaged city at the junction of the New Mexico, Texas and Mexico borders.

Over the past three years, tens of thousands of migrants have traveled here to willingly turn themselves over to U.S. Border Patrol agents outside of El Paso, Texas.

These migrants hope to join the many millions, who’ve been processed and released into the U.S. on the sole condition that they eventually produce a legitimate reason for being in the country.

But a few miles west of Juárez, it’s a different story.

Here, migrants – at great expense and considerable risk – do everything they can to avoid American law enforcement. That’s because some have criminal records that would necessitate their instant removal from the U.S.

Juárez is a crime-ravaged city that sits at the junction of the New Mexico , Texas and Mexico border.

Over the past three years, tens of thousands of migrants have traveled here to willingly turn themselves over to U.S. Border Patrol agents outside of El Paso, Texas.

These migrants hope to join the many millions, who’ve been processed and released into the U.S. on the sole condition that they eventually produce a legitimate reason for being in the country.

But a few miles west of Juárez, it’s a different story.

Here, migrants – at great expense and considerable risk – do everything they can to avoid American law enforcement. That’s because some have criminal records that would necessitate their instant removal from the U.S.

‘Migrants with criminal convictions encountered by El Paso Sector agents include aggravated felons such as sex offenders, child predators and drug traffickers,’ noted one U.S. Customs and Border Protection news release in February. ‘Some of the migrants encountered have gang or Mexican Drug Cartel affiliations.’

Even under President Joe Biden‘s permissive immigration policies, these individuals wouldn’t be knowingly permitted to enter the U.S. So, these illegals find another way.

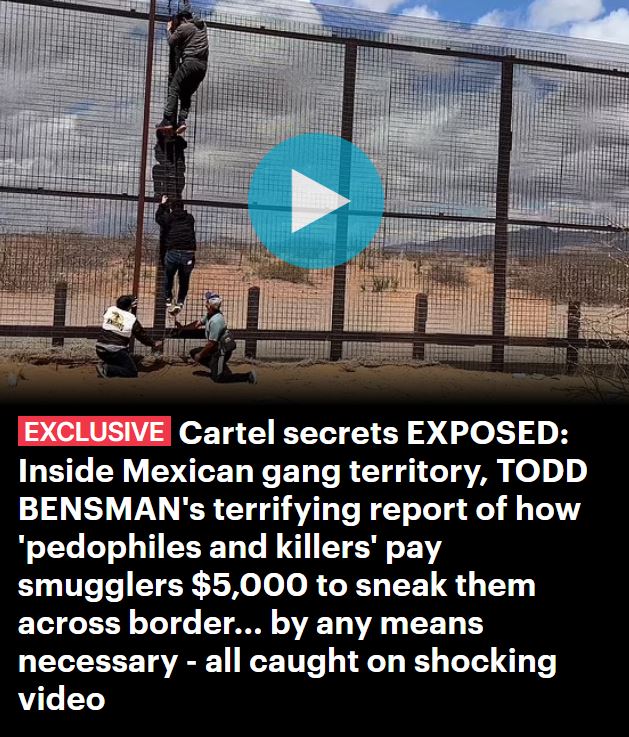

Traveling along Mexico’s Highway 174, which parallels an 8-mile stretch of steel mesh border wall built two decades ago, John (my Mexican-American translator) and I spied five men about to scale a hand-made wire ladder.

We’d skidded to a dusty stop and the migrants dropped to their bellies.

How Texas Tries To Stop Migrants as BP Let’s Them Through

Known to U.S. law enforcement as ‘runners,’ these illegal crossers try to sneak across the border undetected.

Mark Morgan, former Trump administration U.S. Customs and Border Protection Commissioner, told me that some of these ‘runners’ are, ‘among the worst of the worst violent offenders that are now in the United States and “running” is the closest they come to a guaranteed way to enter the U.S.’

John and I identified ourselves to the five men as ‘periodistas’ (journalists) and they started clambering up and over the 17-foot fence to the U.S. side, as I filmed.

Suddenly, two cartel men appeared, seemingly materializing out of the brush.

One of them was visibly armed with a small-caliber silver pistol in his waistband.

They were ‘halcones’ – Spanish for falcons – cartel field spies.

Their job was to protect this lucrative smuggling route.

Illegals pay upwards of $5,000 each for a crossing and pickup on the U.S. side. Often, young women who can’t afford the fee work off their debts in Houston strip clubs.

The ‘halcones’ suspected that we were trafficking migrants through their territory.

‘We know you didn’t pay,’ one of them yelled at us.

‘No. No. No!’ John objected.

‘They’re not ours,’ he pleaded. ‘We’re journalists.’

John showed the cartel soldiers our video and they accepted our story. But they ordered us to stop filming and went to settle up with the runners.

We didn’t wait around to see how things turned out.

As we continued driving along the wall, I kept my eyes on the desert.

Halcones were spaced evenly every few hundred yards. One had a pair of binoculars glued to his face surveilling a section of the wall.

Further along Highway 174, we encountered another group of seven men climbing the wall when Border Patrol vehicles pulled up on the U.S. side of the fence.

The runners retreated and started walking towards the highway when a black Cadillac Escalade drove up behind us.

It was them, again.

The cartel.

But the brazen smugglers weren’t interested in American journalists exposing their operations.

They were there to pick up their customers, who’ll likely continue this cat-and-mouse game with Border Patrol until they find a way to covertly cross.

Another few miles west, I noticed sparks flying from the steel mesh wall.

A man crouched on the New Mexico side welding three-foot, square metal patches over holes large enough for a man to squeeze through.

The worker wouldn’t give me his name but revealed he was a U.S. government contractor hired a year ago to repair the cuts.

‘We just fill the holes, sir,’ he said. ‘Fill everything that gets cut through and then move on to the next one.’

Aren’t you working yourself out of a job, I asked.

‘Honestly, it doesn’t matter,’ he laughed. ‘Every time we fix a hole, they’re cutting another a quarter mile down. It’s nonstop, day and night.’

Individuals who sneak into the country undetected are called ‘gotaways,’ by U.S. Border Patrol. An estimated 2 million ‘gotaways’ have entered the U.S. since President Biden was inaugurated.

Border Patrol sources told me that the San Isidro Border Patrol station that covers this region tally 200 ‘gotaways’ in this area every single night.

‘It’s totally out of control. They’re everywhere,’ retired Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) intelligence operations Captain Jaeson Jones said.

Back in east Juárez, Texas Governor Greg Abbott has largely shut down these illegal crossings.

The Texas DPS, in cooperation with the National Guard and state troopers, has constructed miles of fence and razor wire fortifications that resemble something out of the First World War. And now, heavily armed Mexican police and army troops patrol the area scooping up some migrants and busing them to growing migrant camps in southern Mexico.

But still, sprawling migrant encampments of hundreds have sprung up in the riverbed below the Texas fence line. At night, the migrants light fires to warm themselves. Their camps look like those of an army laying siege to a castle.

On March 21, hundreds of mostly male migrants tore down a fence and charged through a line of outnumbered National Guard and state troopers.

In response, Texas border officials told me they’re now using non-lethal crowd control methods, like pepper balls, which can be fired at crowds and release a temporarily blinding, burning powder cloud upon impact.

Over 200 migrants were charged with participating in that March 21 riot. On Sunday, an El Paso magistrate judge ordered the ‘arrestees’ released from custody pending bail hearings.

The Texan defenses and Mexico’s crackdown have certainly slowed this relentless migrant march to the border, but the flow hasn’t been stopped completely.

At dawn on Wednesday, half a dozen men in hoods crept up from the riverbed camp to chop through the razor wire and chain-link with bolt cutters.

Illuminated by flood lights on the Texas side, the men clipped and pulled apart the fencing, even as a law enforcement vehicle watched on.

Meanwhile, west of Juarez, cartels continue to run their dangerous customers into the U.S. without detection.