Trump’s travel ban eliminated the problem of vetting the histories, backgrounds, hearts and minds of immigrant visa applicants from ungoverned nations like Yemen, Chad, Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia, where record-keeping systems that can track terrorists are severely dysfunctional, or don’t exist. If Biden repeals it, how would the United States filter out dangerous applicants from pre-modern countries where violent Islamic terrorist organizations operate?

By Todd Bensman as originally published November 19, 2020 by the Investigative Project on Terrorism

Presumed President-Elect Joe Biden vowed during the campaign that on “day one” he would rescind President Donald Trump’s “vile” and “Islamophobic” restrictions on U.S. entry from 13 countries, the policy often referred to as the “Muslim Travel Ban.”

But repealing the president’s Executive Order, which applies to countries with terrorism and espionage concerns, portends a return to a very recent era when U.S. security and immigration agencies often were unable to vet travelers from those particular nations.

Trump’s executive order eliminated the problem of vetting the histories, backgrounds, hearts and minds of immigrant visa applicants from ungoverned nations like Yemen, Chad, Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia, where record-keeping systems that can track terrorists (let alone marriages and births), are severely dysfunctional, or don’t exist. Other countries were listed because their governments are hostile and uncooperative on terrorism or espionage vetting matters, like Syria, Myanmar, North Korea and Venezuela. These nations would never help U.S. security establishment filter out terrorists and spies.

If Biden repeals the ban, how would the United States filter for terrorists traveling from pre-modern countries where violent Islamic terrorist organizations operate?

To date, neither the campaign nor the fledgling transition team has acknowledged the problem that Trump’s travel ban ostensibly addressed, defaulting mainly to assertions that its only real purpose was to satisfy an anti-Muslim animus.

Whatever the motive, America’s inability to detect malevolent travelers will become problematic again after travel from the countries is restored. So what does that security vetting failure look like, and what are the potential consequences?

Three of many cases where undesired, potentially dangerous travelers slipped through the pre-ban system illustrate what this could look like once again.

Syria

When 17-year-old Mustafa Alowemer applied for refugee status in Jordan’s refugee camps at the Syrian civil war’s height in 2016, adjudicators in the refugee-friendly Obama State Department had no one to call for a security check in Syria. Alowemer flew into New York on Aug. 16, 2016 and started high school in Pittsburgh. By May 2019, he stood federally indicted for plotting to bomb a church in north Pittsburgh attended by Nigerian Christians “to inspire other ISIS supporters in the United States to join together and commit similar acts…” and also “to take revenge for our [ISIS] brothers in Nigeria.”

It turns out that Alowemer was already a full-fledged ISIS acolyte before applying for his refugee slip to the United States. A month before his arrest, he told fellow ISIS adherents that he had consorted with Jordanian mujahedeen and was arrested with them three times “because I was one of the supporters,” an FBI affidavit said.

After discussing his ideas to blow up the church with undercover federal operatives, he went about collecting components of his bomb, sent a video proclaiming his allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and considered a variety of targets. Alowemer settled on leaving a large bomb inside a bag at the church to be detonated by remote-control.

Alowemer told the undercover agent before his arrest: “We just want to destroy it all.”

Somalia

The U.S.-designated ISIS-affiliated terrorist group al-Shabaab is ubiquitous in Somalia and has controlled territory. That’s one reason that Somalis who apply for refugee resettlement have long presented a stark security vetting challenge to American officials. From 1991–2011, the anarchy of Somalia’s civil war meant no one issued birth certificates, driver’s licenses, diplomas, passports, marriage or divorce documents, or any other government records reflecting that citizens even existed. There was no one to keep tabs on who belonged to terrorist groups, either, in a place where a great many did belong.

When the 20-something married couple Mohamed Abdirahman Osman and his wife Zeinab Abdirahman Mohamad applied in 2013 for U.S. refugee resettlement, embassy workers could not simply call up the current Somali government and ask for a background check or intelligence share.

The couple received visas and resettled in Tucson.

In 2018, federal prosecutors charged the couple with 11 counts of repeatedly lying on their refugee applications and subsequent permanent residency applications. Just about everything they said was a lie, the indictment alleges, including their real names and nationalities, their claim that al-Shabaab had kidnapped the couple and held them hostage, and that Mohamed Osman lost his hands in a terrorist attack. Osman was not even from Somalia; he was an Ethiopian, a Christian country he surely knew would provide intelligence about him to any inquiring American intelligence official.

Under FBI interrogation, Osman admitted that he was a blooded al-Shabaab fighter, as was his brother and extended family. The FBI learned that Osman lost his hands in 2009 while handling explosives during combat operations for al-Shabaab in the capital of Mogadishu. The brother remained a fighter in good standing and committed a 2014 terror attack that Osman and Zeinab knew about after they were in America. Osman sent his brother as much as $32,000 before and after that brother orchestrated the deadly May 24, 2014 suicide bombing of a Djibouti restaurant and had to flee justice, court records show.

The couple pleaded guilty to immigration fraud in April, agreeing to deportation in lieu of prison. At one point during the prosecution, Assistant U.S. Attorney Beverly K. Anderson argued that “if the defendant had been truthful on that application, he and his family would never have been granted refugee status.”

Yemen

Gaafar Muhammed Ebrahim Al-Wazer made it to the United States when there were no restrictions on travel from Yemen.

A federal indictment alleges that Al-Wazer applied for a short-term student visa at the U.S. embassy in Saan’a in 2014. He allegedly swore on the documents and during an interview with a State Department consular adjudicator that he had never belonged to an armed militia group, nor received military training. He swore he’d never belonged to any particular tribe, like the Iranian-backed Shiite Houthis whose virulently anti-American “Ansar Allah” battalions had just seized the capital in an armed coup.

Al-Wazer’s application to study English was approved the same day as his interview, court records show. The 25-year-old came to America in December 2014 and settled in Altoona, Pa.

Not until May 2016 did the FBI discover via a tip that Al-Wazer had fought with the rebels. The suspect allegedly unburdened himself of increasingly fervent hatreds on his Facebook page, where he wished “death to all Americans, especially Jews,” and vowed that he would stay on the path of jihad.

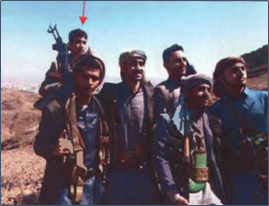

The Bureau found online pictures showing a heavily armed Al-Wazer and his brother with Houthi rebels in remote mountainous settings of Yemen.

One message under a group photo of fighters that Al-Wazer, who was among them, “liked” stated “these men have taken an oath to stay on their path and…will never be humiliated on the path to jihad. The author further wishes death upon the United States and Israel and wishes victory to Islam.

Discerning the Malevolent from the Benevolent

These cases and others should serve as reminders to incoming policy-makers that what Trump often notoriously called “extreme vetting” should remain a national priority.

If it won’t retain a travel ban, the new administration should consider pressing forward with the National Vetting Center, established under a separate 2017 executive order. It aims to make more information from intelligence and law enforcement agencies accessible for vetting visa and immigrant applications. While it is up and running under U.S. Customs and Border Protection, it remains an early work in progress, officials have told me. The center is envisioned as “a collaborative, interagency effort to provide a clearer picture of threats to border security … or public safety posed by individuals seeking to transit our borders or exploit our immigration system.”

But travelers from the 13 countries and others will remain a vetting challenge even with the center running on all engines, given the absence of information in origin countries. There can be little doubt that Syrians, Somalis, Yemenites and others from the travel-restricted restricted countries have suffered and deserve American sanctuary if their claims could be verified.

Unfortunately, the true hearts, minds and experiences of most people coming from these countries probably can’t ever be plumbed or verified. And so the value of security provided by Trump’s blanket exclusions vies against the value of Biden’s emphasis on open-gates.

The greatest value of Trump’s travel restrictions list was that it eliminated the high-stakes gamble that America’s security vetting systems could suss out terrorist actors from countries with such governance problems. Perhaps its greatest weakness, arguably, was that it did not include enough countries with records-keeping deficiencies or diplomatic hostility.

The coming Biden administration has its reasons for moving the country from Trump’s play-it-safe table game to the gambler’s table, but losses there are a more certain outcome.