By Todd Bensman as published August 19, 2021 by the Center for Immigration Studies

AUSTIN, Texas — However many U.S. entry visas the Biden White House decides to grant Afghans, those who find the legal way blocked have a tried and true end run at their disposal: the stress-fractured American southern border.

Well-established routes and smugglers are in place — and have been for years — to move Afghans over the US southern border in spite of any Washington limitations on legal visas. Once through the land border, those who decide of their own volition to reach it usually get to stay permanently anyway.

When President George Bush’s and President Barrack Obama’s Washington put visa restrictions on Iraqi refugee resettlement during that war, hundreds of Iraqis skirted them in a few short years by coming in over the border and claiming asylum instead, a much more accommodating process for them. When President Donald Trump’s Washington put visa restrictions on Syrian refugee resettlement during the civil war and ISIS caliphate, hundreds skirted all that noise, came in over the border and stayed that way.

Afghans have always come over the border too, albeit in very small numbers, because there’s a route from there to here through the Americas. But now, significant percentages of that South Asian nation can be expected to flee well-remembered draconian Taliban rule. Expect many more Afghans to start trammeling the international route once they realize all the legal visas are taken, especially now that most of the world is well aware the southern border has fallen into un-defendable chaos.

One problem is that, with any extra Afghan traffic to the US border, Americans can also expect these Afghans won’t be vetted much for insider-threat security. Not any more than those who come the legal way.

Afghan immigrants who illegally arrive as strangers at the southern border must be regarded as an especially acute security threat, if years of “green-on-blue” attacks against American troops are any indication.

An emblematic Afghan “security threat” who reached the Texas border

Consider the case of border-crossing Afghan Wasiq Ullah, a former interpreter for the US military who was denied one of the special immigrant visas reserved for those who helped the American war effort. So he did the border end-run on January 19, 2018, reaching Brownsville, Texas and then accessing the usually more forgiving alternative system, the one for asylum.

As I wrote in 2019, he allegedly achieved the journey with the help of another former Afghan interpreter for US forces now living in New Jersey, who was (apparently inadvisably) rewarded a special immigrant visa in 2009. Mujeeb Rahman Saify now stands federally accused of allegedly conspiring with a Pakistan-based smuggling network to transport Ullah to the southern border (and at least one other Afghan who couldn’t get a visa but also made it through Mexico).

In this rare case, Ullah didn’t get asylum because fortunately he’d left behind an easily discoverable record with US forces in Afghanistan that pegged him as a national security threat. According to court records from Ullah’s appeal of his asylum denial, Ullah had worked as a linguist for the US Army at Camp Leatherneck from January 2011 to January 2014, even though a brother was terminated as a linguist for involvements with Taliban sympathizers.

But Ullah ran into trouble when he applied for a special immigrant visa to come live in the United States. He failed a routine polygraph in answering whether he was a member of an anti-coalition group or had ever participated in an attack against coalition forces.

As a result of that and other investigation, the Americans not only denied Ullah the visa; they declared him ineligible to ever receive one, fired him from the linguist job, and barred him from all US installations in Afghanistan. A counterintelligence memorandum judged that Ullah was suspected of affiliating with a foreign intelligence security service, “such as the Taliban,” which meant Ullah had some communications with a suspected foreign intelligence officer and could pose a “force protection threat,” an appellate court record stated.

No matter any of that, though. In September 2016, with the alleged help of special immigrant visa-holder Saify in New Jersey, Ullah began the end run. He paid smuggler’s $16,000 to reach Brownsville, Texas from Mexico.

Thankfully, in this case, adjudicators found the military records about him and got him ordered deported instead of let in to pursue asylum for years on end.

But the reasonable expectation is other Afghans who use the same smuggling routes won’t have discoverable records residing with the US military.

They are going to start showing up at the border once the Biden administration draws lines on how many Afghans get to fly in on legal visas, meaning pretty soon.

How many Afghans make this trip and how?

Total numbers of Afghans reaching the southern border over the past decade or so have been relatively miniscule when compared with totals, some years reflecting no Afghans showing up or in single digit numbers.

More Afghans seem to turn themselves in to Customs and Border Protection officers manning established border Port of Entry than get caught by Border Patrol crossing through the brush between Ports of Entry.

US Customs and Border Protection Data reflecting apprehensions between Ports of Entry and a Center for Immigration Studies FOIA request for self-presentations at Ports of Entry show that 165 Afghans reached the US southern border between 2010 and 2020. (CIS’s FOIA for self-presentations at Ports of Entry go through 2018, so another dozen or two could be added to the tally).

Beyond general global knowledge that America’s southern border presents a glowing opportunity for entry under Biden administration policies is the fact that Afghans learned the game well during the European mass-migration crisis, when more than a quarter million of them entered over borders there.

Afghan migrants and refugees have proven willing to bypass the immigration rules and restrictions of more desirable western nations but also know how to reach the American border.

In my new book, America’s Covert Border War, the Untold Story of the Nation’s Battle to Prevent Jihadist Infiltration, I address how illegal immigration from South Asian countries works.

In it, I cite an April 17, 2016, The Washington Post story documenting that Afghan economic immigrants the Europeans were then starting to block at their borders had shifted to an American southern border route that involved flying through Cuba first and then to staging countries in South America. But that rare story didn’t mention that there were many other ways to reach the border.

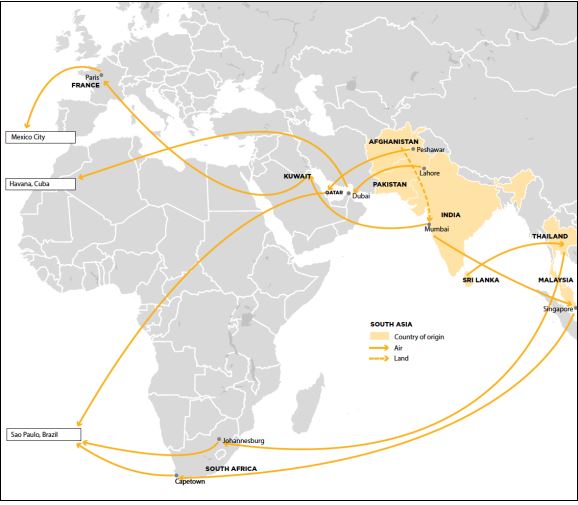

In the past, my research shows, Afghans (and next-door Pakistanis too) have first flown into Gulf States like Qatar and Dubai or even France for transfer flights to the western hemisphere. Routes to the Americas also can run through India, Singapore, and South Africa. From those countries, Afghans and Pakistanis eventually make their way into Brazil and Ecuador. From there, smugglers move them on the ground from country to country through Panama and on up into Mexico.

As the Afghanistan crisis develops, pushing potentially millions of Afghans to flee just about anywhere they can, Americans and homeland security authorities should remember to look beyond merely the legal visa policies that are sure to solidify.

Human smuggling bridges connect Afghanistan and all of the surrounding nations to a southern border that all know is wide open and vulnerable but also that it can carry malevolent actors alongside the benevolent ones.