With more doctors per capita in the world, Cuba has deployed more than 1,000 physicians, dentists and psychiatrists to Angola and other African countries where leftist movements that Cuba once helped are now governments in power. The two dozen countries that Cuba is targeting include southern nations of particular strategic or economic value such as Namibia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Cuba Uses Humanitarian Aid in Fight for Foothold in Africa

Expertise from doctors, educators fulfills need in developing countries…

The Dallas Morning News

LUANDA, Angola Fall – Fidel Castro is deploying a new sort of soldier

across the African continent, to lands where his armies not so long ago

fortified socialist struggles in battle against the West.

The Cuban legions of today are doctors, educators and technicians, and Mr.

Castro has engaged them in a post-Cold War strategy of sowing good deeds.

Embargoed by the United States and abandoned by the former Soviet Union, cash-poor Cuba is finding a big welcome mat at the doorsteps of old Cold War friends of immense potential wealth.

The good mutual feelings are evident in the pulsating Havana Cafe, a trendy

downtown Luanda nightclub themed to honor Cuba for its combat sacrifices in oil-rich Angola fighting

Western oil executives party under large posters of the bearded Cuban leader Che Guevara and singer Carmen Miranda, drinking Cuban rum and smoking Cuban cigars for sale at the bar.

A few blocks from the club stands a towering monument built to honor the

2,000 Cuban soldiers who died successfully defending Angola’s socialist

government against the rebels.

“They helped Angola win independence and keep independence, despite the

Americans,” said the club’s owner, Francisco DeAlmeida, a native Angolan.

“We are like brothers.”

Cuba, which has the most doctors per capita in the world, has deployed more than 1,000 physicians, dentists

Since 1996, for instance, more than 400 Cuban doctors have been sent to

President Nelson Mandela’s South Africa, where Cuban soldiers once helped

the anti-apartheid African National Congress wage war.

Mutual cash needs

Some foreign policy analysts say the developing Cuban affair with Africa has a pragmatic motive: Cash-strapped, diplomatically isolated governments on both sides of the Caribbean need the trade and cash to help them hold out for better times.

Hard-pressed Cuba is still struggling to make up for the $3 billion a year in

lost Soviet aid and to shake off a debilitating U.S. economic embargo.

Countries like Angola, analysts say, need only stability to fully develop their

enormous natural resources.

“There’s not much trade between Africa and Cuba, but there’s always the

possibility of that the future,” said Wayne Smith, an adjunct professor and

Cuba expert at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The doctors pay off,

both in terms of winning friends and potential trading partners but also in

terms of immediate cash flow.”

South African companies, under a new post-apartheid

of former leftists, are penning big contracts with the Cubans; one company

has just signed a partnership deal to provide Cuba with 15,000 diesel

engines.

Cuba is finding ready markets for its famous cigars and rum. And exchanges of students and professionals are rising, signaling expectations of deeper relations to come. More than 3,800 African students from 19 countries were studying in Cuba in 1998.

On a speaking tour of Africa late last year after one by President Clinton,

Mr. Castro found red-carpet welcomes where his presence just a few years

earlier would have been politically untenable.

Cuban officials say Mr. Castro’s recent efforts in Africa are part of a

Cold War days. Short of cash but abundant in trained professionals, the

government sends people as

“It’s a continent that has much significance for us in terms of the battle for

justice,” said Luis Fernandez, a spokesman for the Cuban Interest Section in

Washington. “We have a lot of economic problems, and we’ve been a victim

of blockade policy, and despite all that, Cuba gives its hand to these people.

It’s part of our philosophy, and we’re not looking for any benefit”

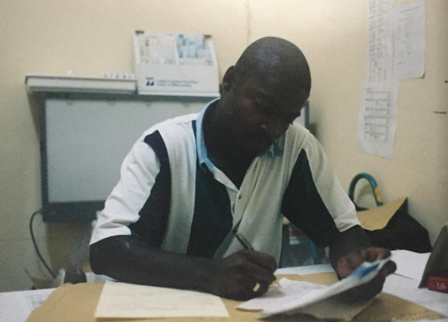

During the Cold War, Cuba had always sent doctors and teachers alongside

soldiers to help press the socialist ideal, at no charge. But now, contracts

with host governments earn the Castro regime between $1,000 and $2,000 a

month per person. The workers themselves say they get small cash stipends,

food and shelter and are closely watched to make sure they don’t defect.

Mr. Fernandez says the income is used only to sustain Cuba’s Africa policy.

Filling a void

For some new African governments. Cuba’s help comes at a particularly

needy time. Governments emerging victorious from bush wars found that

well educated white doctors and teachers had fled. It was clear that Western aid or

Namibia, after a long armed struggle helped by Cuban combat soldiers, had

nowhere else to turn when it gained independence from South Africa in 1990. The country deeply appreciates the 55 Cuban doctors now treating the

rural poor, said Dr. Libertine Amithila, minister of Health and Social Services. Cuba also agreed to train 10 Namibians as pharmacists in Cuba last year and will take 15 more this year, she said.

“When we came back from the war, the shortage was

“We thought, what do we do? We had to ask friendly countries for help, and

the Cubans came and did

without them.”

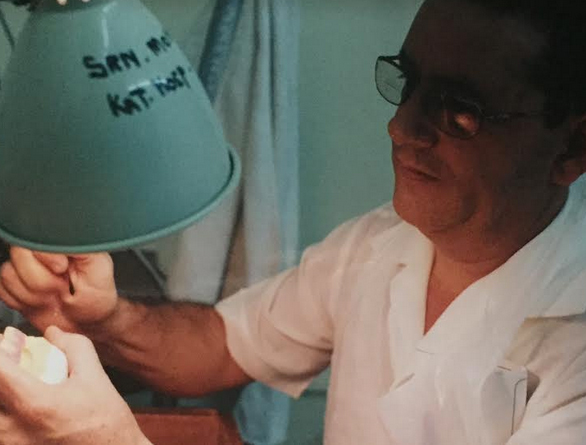

Angola, once a Portuguese colony, lost most of its doctors when the white

population fled a rebel advance in 1975. More than 20 years of civil war

later, about 80 Cuban doctors in eight government hospitals help ease

continuing chronic shortages. Others work in tidy private clinics catering to

wealthier foreign clients in the country’s oil industry.

Typically, the doctors are volunteers who work under two-or

contracts often in isolated communities. Many leave families behind but

send home what little cash they can. A few have defected to Western

countries in recent years, Cuban officials

But many Cuban doctors, some living in genuinely harsh conditions say the

work is rewarding, although they lace such talk with politically correct

commentary.

“This is a very good country that has suffered much in the past,” said Dr.

Manuel Lopez Martinez, a neurologist from Havana who served in Ethiopia

before coming to Angola six months ago. “This is not for us to get anything

out of it but for us to help create development because Africa is a very big

stalk in the life of the world.”

Dr. J. Manuel Almeida Lorente, a psychiatrist who directs a private health

“Luanda is a hard place to live, with a certain level of violence and a lot of

diseases,” he said. “But what I like most is the way the people treat us. They

really love us.”

Indeed, there is ample evidence of an abiding appreciation for the Cubans

among Africa’s poor.

Cuba helping out Cold War allies with an infusion of good deeds

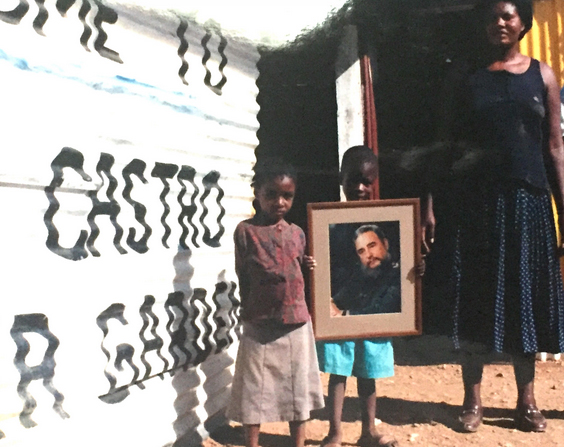

In one of the Namibian capital’s poorest slums stands a school affectionately named Fidel Castro Kindergarten. Its tin walls are painted in bright colors with the Cuban leader’s name spelled out in large black letters, Framed photos of Mr. Castro grace walls inside.

“I am a freedom fighter,” said Mary Shapumba, the school’s teacher,

referring to her support of guerrillas who once struck Namibian targets from Angolan bases. “When we were abroad in Angola, the Cubans and

Cuban friendship societies also have formed elsewhere to pursue other

monument projects and to curry public favor for Cuba.

“People who put their life on the table for your independence create an

emotional attachment,” said Ephriam Jane, a spokesman for the NamibiaCuban Friendship Association. “People feel indebted. You can’t forget your friends.”

Resentment

But while African governments and their poor dependents deeply appreciate the attention, they also suffer the anger of anti-Communist whites. In South Africa, about 80 percent of the country’s doctors are whites who worked mainly in big cities and were schooled in elite universities that largely excluded black students. After apartheid fell in 1994, the new black government quickly realized it had to get medical services to rural blacks and to get black students trained.

But controversy has broken out over programs to import 600 Cuban doctors

and send black youths for medical training in Cuba. Some white doctors have accused the Cubans of inferior training and work, prompting a number of malpractice investigations and a suspension of the health department’s plan to import the last 200 doctors.

“My feeling is that the quality of doctor required is best produced in South

Africa,” said Dr. David Morrell, who chaired a committee sent last year to

assess Cuba’s medical schools and found them wanting. “A lot of the

criticism is that the standard of medicine is low. But the feeling also is that

even if they’re not suitable, a Cuban doctor is better than no doctor.”

But Khangelani Hlongwane, a spokesman for the country’s health

former enemies take power.

“They’ve been told all their lives that Cubans were god-awful, horrible

Communists,” he said. “But Castro said to us, I can give you 600 doctors.

Not next month, not tomorrow but now. Not many countries can do that. But Cuba, Cuba could do that.”