The Stanford organization financially destroyed Jews south of the Texas border with its devastating pyramid scheme. For an idea of the scale, estimates then had it that at least 3,500 of Mexico City’s 40,000 Jews collectively lost at least $500 million

By Todd Bensman

Before the whole sordid episode passes into the abyss of history, perhaps where it belongs, the rapacious R. Allen Stanford Ponzi rip-off of a decade ago deserves its epilogue.

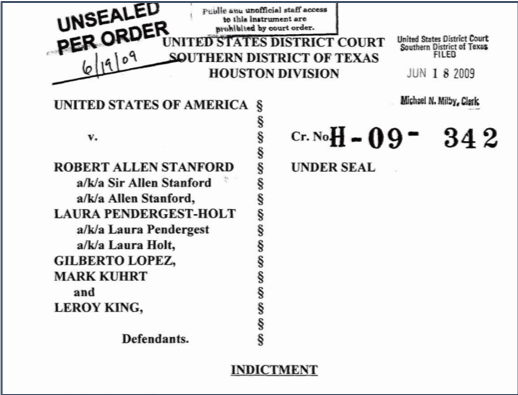

At a staggering $8 billion, the Stanford Ponzi stands as the world’s second largest next to the one perpetrated by Bernie Madoff. The expansive, intercontinental Department of Justice and Security and Exchange Commission investigations made some headlines back in 2009 when they finally ensnared the Houston-based Stanford and five of his cronies in the United States and in the Caribbean island nation of Antigua, which earlier had actually knighted “Sir” Stanford.

Now comes a DOJ press release, mentioned almost nowhere in the media universe, titled “Last Defendant in Stanford Investment Fraud Scheme Extradited to U.S.” Stanford will die in prison with his 110-year prison sentence. But this judicial book-end is worth a mention now to remind and warn that, if carnivorous animals like Stanford and Madoff were free to prowl back then, they also probably are targeting Jewish communities again somewhere, right now.

Preying on Latin America’s Jews

Working as a news reporter in Stanford’s Texas when this was all breaking 10 years ago, financial fraud wasn’t something I covered. But a unique characteristic of this particular scheme captivated me when an involved lawyer in San Antonio casually mentioned it to me at a party. It was that the operation run by “Sir” Stanford, who liked to portray himself as a pious fundamentalist Christian, had laid financial waste to Jewish communities from Mexico City to Caracas, Venezuela.

The lawyer at the San Antonio party was representing a group of Hasidic Jews in Mexico City and others in Venezuela whom the Stanford organization financially destroyed. Jews south of the Texas border weren’t the only ones victimized, of course, nor did it seem they maliciously selected based on religion; an estimated 30,000 people were victimized worldwide. But the damage done to these communities was disproportionately high. For an idea of the scale, estimates then had it that 3,500 of Mexico City’s 40,000 Jews collectively lost at least $500 million, lawyers representing Jewish victims in civil recovery litigation told me.

How could such a weird thing like that have happened to exotic communities I didn’t fully realize were even living in those countries? The answer I came up with for the now-defunct (paywalled) GlobalPost news organization, after wearing out a lot of shoe leather: the same way Bernie Madoff did it among American Jews, by exploiting a confidence-building phenomenon known to criminologists as “ethnic affinity” crime. It’s worth revisiting today.

But first, the “Last Defendant” at the heart of DOJ’s original 2009 indictment is Leroy King of Dickerson Bay, Antigua, where the gregarious, large-living Stanford spread money around like a Saudi prince and ran his campaign sucking bank accounts dry throughout Latin America. The scheme worked like this: Stanford and his sales people would travel around the world beguiling prospective investors with promises of high return rates, word of actual “returns” paid by earlier investor money would spread through family and friend networks, generating more investment. Stanford and his cohorts would fly the cash out aboard private jets and skim lots of it off for their own extravagant uses.

It’s unclear how authorities finally caught up with King, the last of these bandits, and extradited him to Houston where he will be prosecuted in 2020. A fugitive since indictments were unsealed in 2009, King was somewhat of a bit player with a key role in the Ponzi. As a regulator in Antigua’s Financial Services Regulatory Commission, King is accused of accepting $100,000 in bribes from Stanford to let stand the inflated value of the mastermind’s hollowed out offshore “bank,” which promotional brochures featured as a mother lode of out-sized returns to investors.

A Nice Jewish Boy

King wasn’t apparently involved in the reaping of Jewish money. Neither was his bribery patron. Stanford is a graduate of Baylor University, a Baptist institute in Waco, Texas. He reportedly prayed with his sales force and used Christian connections to raise money.

Having some money to steal appeared to be the main prerequisite. It all allegedly started when Stanford hired a Mexican Jew named David Nanes Schnitzer, who knew where some was because he was born and raised in Mexico City and had a Jewish-Mexican wife and children. Now only recently serving time in Mexican prison for his deeds, Schnitzer opened a sales operation covering Mexico, Panama, Venezuela and other parts of Latin America. He hired local Jewish sales people, gave money to local Jewish charities, and went to work on the people who had known him his whole life, according to victims and his Texas lawyer in 2009.

This is how ethnic affinity fraud works.

“The Jewish community is very tight, so if someone comes up with a great idea recommended by another person you know, you listen,” Sofie Frieman, chief of a charity that lost everything in the scheme, told me in 2009. “It’s word of mouth. If your brother and brother-in-law, and the friend of your wife, is making money you might go ahead and participate. You would never think in your life, if you’re a widow, that a nice Jewish boy is going to fool you in a scam, because you know his mother and you never think he’s going to take advantage. This is where it’s most painful.”

Not long after Schnitzer brought Stanford to Mexico City’s Jews, he instituted an aggressive marketing campaign that targeted the community. The company became a major, consistent corporate sponsor of cultural and sporting events. It doled out generous amounts of money to local charities and organizations, then hit everyone up to invest it all.

Stanford advertised heavily in community publications, including a well-read sports center newsletter about teams the bank sponsored, Renee Shabot told me. She was director of Tribuna, an organization that acted as a liaison between the Jewish community and the non-Jewish world.

The same strategy of targeting wealthy Jews and hiring Jewish sales officers also apparently unfolded in Caracas, Venezuela, instilling a comfort level in potential clients like those in the smaller community of 14,000. Rabbi Penchas Brener of the city’s largest synagogue told me at the time that he lost $50,000 to Stanford from the endowment of an important local foundation he headed.

Brener said he felt almost no wariness about reaching out to one of Stanford’s “account executives,” a local Jewish man whose family he’d known for decades, to invest his foundation’s $50,000 reserve account.

“I didn’t pay too much attention to the credentials,” Brener said. “They were Venezuelan Jews. They worked for a bank. He didn’t have to convince me; I called him. This was made easier, so to speak, by the fact that he was Jewish. I don’t know how hard it hit the community, but I know it hit.”

Another Stanford salesman recruited from Venezuela’s Jewish community told me he told widely throughout Latin America, including to Panama’s Jewish community and to Jews in Europe and elsewhere.

Shnitzer’s lawyer in Houston told me his client had no clue he was selling a Ponzi scheme. But amid civil lawsuits in the United States and expected criminal action, Shnitzer went on the lamb in 2009. He was captured hiding in Belize in 2015 with a variety of false documents and plenty of money but was able to go underground again after being granted bail. Mexican authorities finally captured Schnitzer in January 2017 on fraud charge arrest warrants after he arrived on a flight from Cuba.

Recovery Operations Ongoing

If no one else is interested in the last gasps of criminal justice in this affair, victims in Mexico are still waiting to get paid back something of what they lost. According to Mexican media reports this year, lawyers have maintained their litigation all these years and think they will recover $8 for every $100 lost.

Texas lawyer Edward Snyder, the guy who first told me about all this at the San Antonio party told El Financero in Mexico that old Stanford bank accounts have been found but not with much money in them.

“The big problem is that Stanford’s accounts do not have funds to pay the victims, so we have worked through litigation against third parties, that is, against complicit persons or companies, who helped commit the fraud. It is a very difficult case, much more complicated than Bernard Madoff’s.”