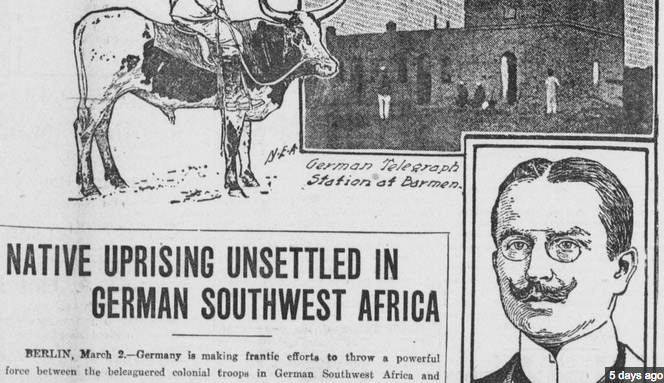

From 1904 to 1915, the Kaiser’s troops in Germany’s then- Southwest Africa colony systematically exterminated as many as 80,000 members of the rebellious Herero Tribe. It was a scarcely known slaughter of Teutonic efficiency that produced forced labor camps, sex slaves and the first academic “studies” of supposed Aryan superiority, a prelude to the Jewish holocaust. Now the tribal remnant in north central Namibia wants justice.

Update: In January 2017 (Nearly 20 years after this story was published),

the tribe filed a class-action lawsuit seeking reparations from Germany. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/06/germany-sued-reparations-colonial-era-genocide-

The Dallas Morning News

1998

OKAHANDJA, Namibia – In Europe,banks and governments are owning up to their complicity in Nazi crimes against Jews with reparations and apologies. In Asia, Japan finally apologized for its brutal colonial rule over Korea and paid some sex slaves for their World War II-era ordeals.

But here in this remote pocket of Africa, where historians say the first seeds of the Nazi holocaust were sown, surviving members of a scarcely known tribe called the Herero wonder why the reparations bandwagon is passing them by.

The Herero leaders say the 20th century’s bleak history of genocide started with them in this small, dusty farming burg in Namibia, once the German colony of South-West Africa.

From 1904 to 1915, the Kaiser’s troops systematically exterminated as many as 80,000 Herero, a scarcely known slaughter of Teutonic efficiency that produced forced labor camps, sex slaves and the first academic “studies” of supposed Aryan superiority.

Herero leaders, frustrated that justice eludes them while other groups find atonement, are pressing Germany to remember them, too – with an apology and compensation.

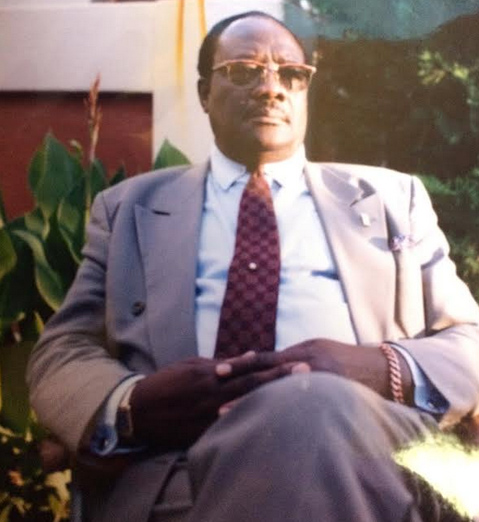

“We’re equal to the Jews who were destroyed,” said Paramount Chief Kuaima Riruako, the Herero king. “The Germans paid for spilled Jewish blood. We say, “Compensate us, too!’ It’s time to heal the wound.”

Bensman

But unlike the cries of Jewish inheritors of stolen Swiss bank accounts and former slave workers, Herero pleas ring faint.

Modern Germany, still a powerful influence in Namibia, has so far offered only sympathetic words – no apologies. The Herero can find no help from their national government either, owing to tribal politics. Chief Riruako said his efforts to enlist the support of American Jews during trips to New York have gotten nowhere.

“For 10 long years, I have been saying this and nobody will come to our rescue,” said the chief, whose royal family lost all of its land and cattle during the period. “Even the Americans don’t give a damn.”

German Embassy officials in Washington and in Namibia’s capital, Windhoek, note that this country of 1.6 million people gets more German development aid per capita than any other, about $500 million since 1992.

“And that is because of historical reasons,” said Rolf Ulrich, counselor general of the Windhoek embassy. “Certainly, a lot of thinking has been going on in Bonn and Windhoek about this. But the idea continues to be that Namibia is the largest recipient.”

A number of prominent U.S. Jewish advocates and organizations involved in reparation efforts seemed unaware of the Herero plight or its connection to their own.

“To be honest, I know nothing about it at all,” said Gideon Taylor, executive vice president of the Conference of Jewish Material Claims against Germany, a group that has negotiated $50 billion for Jewish victims of the Nazis.

The Herero believe that their past and present obscurity – and the fact that their story did not emerge until the 1980s – works against them.

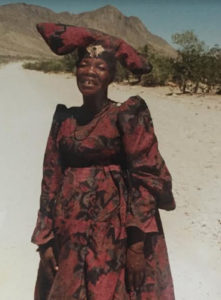

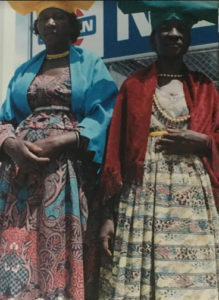

Many outsiders may know of them only from travel book photographs depicting their highly unusual sense of fashion.

Herero women commonly wear distinctive hats and colorful, hand-made hoop skirts that rustle and sway when they stroll the deserts. Some even twirl parasols.

Many Herero men, sporting broadcloth suits and old German uniforms or copies of them, add more Victorian dash. Though quaint, these fashion oddities pay a dark, unintended tribute to their German oppressors; the clothing style was adopted from the first German missionaries who entered the area in the 1870s.

The discovery of diamonds in the 1890s brought settlers who began pushing the cattle-herding Herero and Nama tribes from their traditional communal territories. The rival Nama rebelled against the Germans first but were quickly put down with Herero help – hence the German uniforms that Herero men still wear today.

By the turn of the century, though, the Herero were feeling the pinch of German land grabs and abusive rule that often included arbitrary lynchings.

It was in Okahandja, the Herero capital, that Herero leaders mounted an armed rebellion in 1904. Their campaign – against military targets only – went well initially.

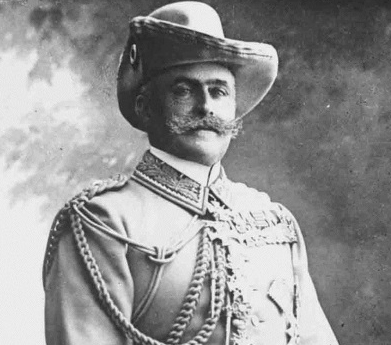

But Kaiser Wilhelm II sent Lt. Gen. Lothar von Trotha in with 10,000 troops. The general was already well-known for his brutal campaigns against uprisings in German East Africa.

According to recent historical works, the general soon vanquished Herero troops and embarked on a campaign of annihilation against civilians that was to hint ominously at the Nazi holocaust to come.

Gen. von Trotha drove 80 percent of the tribe into the Omaheke Desert, after poisoning the water holes. While soldiers blocked escape, he issued the “Vernichtungsbefehl,” or extermination order: “Within the German borders, every Herero, whether armed or unarmed, with or without cattle, will be shot. I shall not accept any more women or children. I shall drive them back to their people” in the poisoned Omaheke.

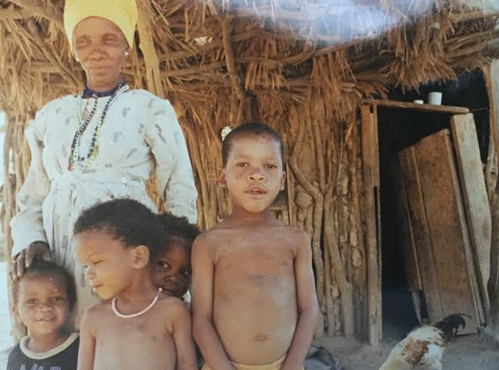

Those who were not bayonetted, shot or starved, perhaps 20,000, were condemned to slavery on German farms.

There were Herero “comfort women,” slave camps, identification tags, murder with impunity. German geneticists conducted racial studies of presumed Herero inferiority, theories that Adolph Hitler later adopted as Nazi philosophy and which Nazi universities taught.

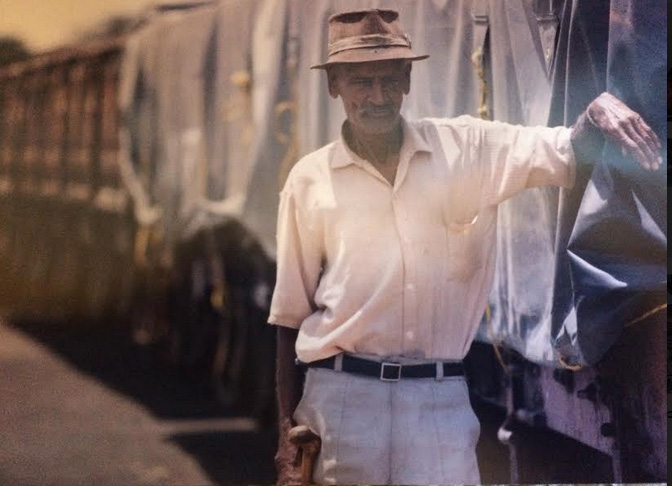

Frans Muningua, born in 1904, is perhaps one of the last Herero old enough to remember some of what happened. Telling his story for the first time, he said his mother was initially overlooked during the German roundups. But she was captured later and given to an army captain, who raped her. Mr. Muningua said he believes that he got his blue eyes from that German officer. He and his mother were forced daily to pull heavily laden railcars along Okahandja’s tracks.

“We were worked hard, like donkeys,” Mr. Muningua said, walking with the aid of a cane along the same tracks. “My mother hated them.”

The gruesome chapter came to a close in 1915 during World War I, when allied troops of the Union of South Africa drove the Germans out. Namibia then became a territory of South Africa and remained so until Communist insurgents took over in 1990, establishing a modern democracy.

The Herero experience was always Namibia’s dirty little secret, living only in the tales of Herero elders, until East German journalist Horst Drechsler documented it in his 1980 book We Shall Die Fighting.

Lora Wildenthal, an MIT professor who specializes in German history, said the South African regime that ruled Namibia until 1990, backed by white German descendents, had a vested interest in suppressing the story as it fought the Communist insurrection.

“They always knew about the war, and the Herero had long said it was a genocide,” she said. “But there wasn’t a big hue and cry to lay out big pictures without it being painted as Communist propaganda.”

Herero leaders say independence motivated them to begin seeking reparations, when it became clear that the new democracy would condemn Herero descendents of the massacres to second-class citizenship.

They say that is because the Ovambo tribe, which dominates Namibia’s ruling South-West Africa People’s Organization party, SWAPO, is more numerous and prosperous for having escaped the German onslaught. The much diminished Herero, about 100,000 today, accuse SWAPO of diverting the $500 million in German aid to Ovambo voters. So, they want Germany to set up a fund for Herero purchases of land and cattle.

“What we are saying is that the Germans, because they only killed the Herero and no one else, must uplift us,” said Gottlob Mbaukaua, an opposition party Herero leader in Okahandja.

The Herero also expect continued opposition from Namibia’s 25,000 white German-speaking citizens. They control more than half the country’s farmlands, much of it formerly Herero territory, and remain influential in Namibian politics. Many of them deny that a holocaust ever happened and oppose reparations for the Herero.

“Genocide is a relative term if you are involved in a war and you lose,” said Eckhart Mueller, chairman of the German-Namibian Cultural Organization. “I think they’re taking a long shot to get some money. If not genocide, it will be something else. I think we must bury the past and look to the future.”

It may be that the history itself stands in opposition to Herero claims. The tribe is hardly the only victim of European colonial atrocities in Africa. Belgians under King Leopold II slaughtered native Congolese wholesale during the last century. The French brutalized natives in Equatorial Africa. The British killed natives throughout the continent.

But African history specialists say the German campaign against the Herero was unique.

“This is not tribal conquest. This is actual genocide,” said Dr. Atieno Odhiambo, professor of 20th century African history at Rice University. “In terms of scale of destruction, there’s really nothing to compare in sub-Saharan Africa. This was deliberate policy.”

Still, MIT’s Ms. Wildenthal said one reason no European power seems eager to take up the Herero cause is fear that a payoff would invite multitudes of similar claims for colonial-era crimes.

“Imagine what Britain would owe,” she said. “I don’t think any former colonial power will go anywhere near this.”

A flicker of hope for the Herero appeared earlier this year when a new government under Gerhard Schroder replaced that of longtime German Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

The new coalition government includes the tiny Green Party, the only political entity that had ever taken Herero claims seriously. A Green Party member was even named Germany’s new foreign minister, Joschka Fischer. One of the new government’s first acts was to start work on a permanent fund to compensate slave laborers under Hitler.

Martin Kotthaus, a German embassy spokesman in Washington, said recently that while still early, the new government has given no sign that policy toward the Herero is going to change anytime soon.

But Chief Riruako, emboldened by these recent developments, said he won’t quit until it does.

“We have already written a letter to let them know we are willing to talk,” he said. “We don’t want to waste any more time.”