(As published by the Center for Immigration Studies)

By Todd Bensman on December 13, 2018

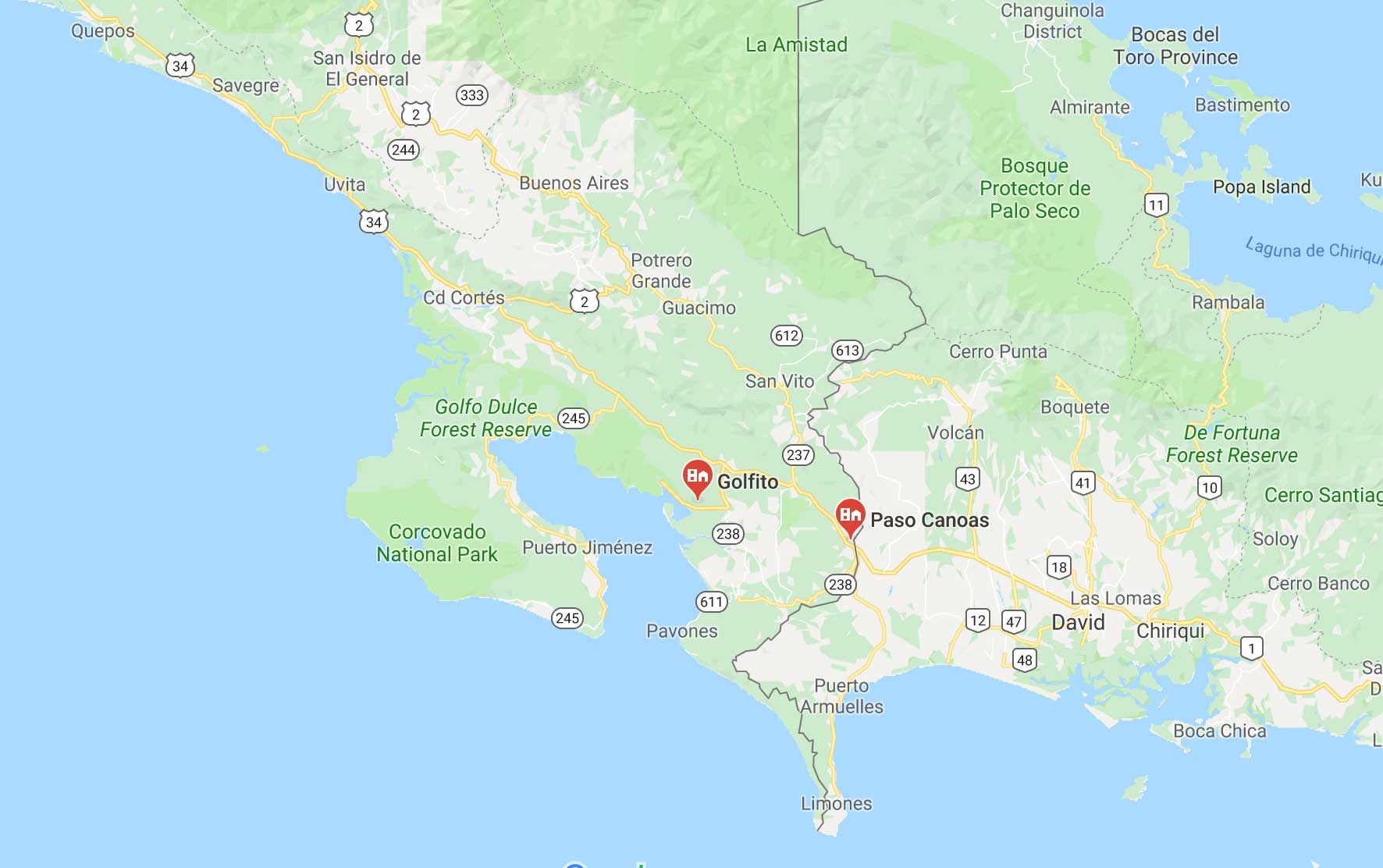

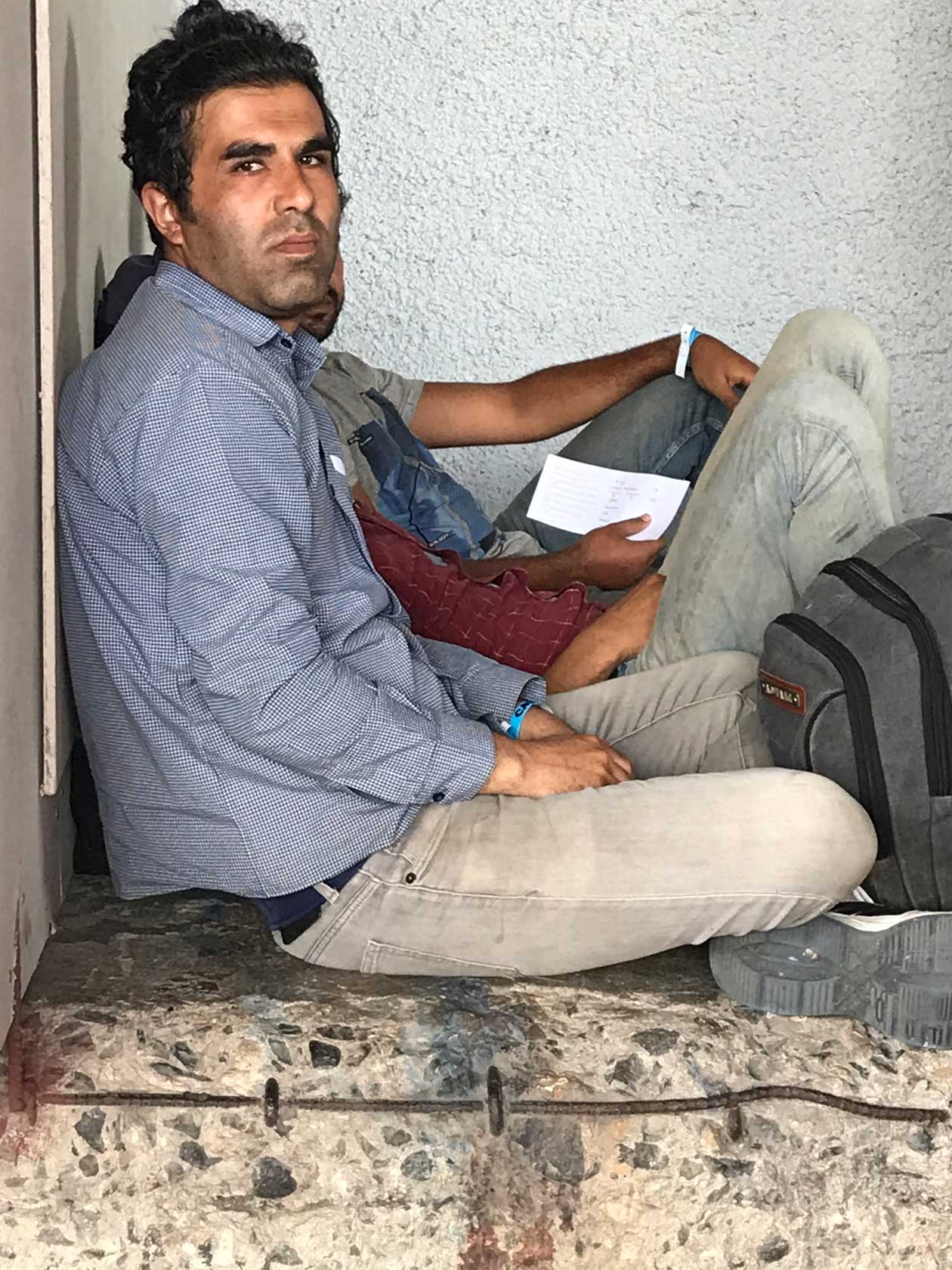

GOLFITO, Costa Rica — The four Iranians told me they first saw me hundreds of miles south, in a Panamanian migration camp 15 miles off the main road, at the end of a dirt track in the Darien jungle. The one who spoke some English told me they had been “frightened” at the sight of me, by the sudden appearance way out there in the jungle of someone who could only have been some sort of American law enforcement or intelligence officer determined to interrogate them and maybe send them home.

In fact, a certain Panamanian government friend told me where that camp was, and sure enough, it was in the jungle, filled with migrants from places with a lot of Islamist terrorist group activity, like Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Bangladesh — and, of course, Iran, a U.S.-designated state sponsor of terrorism. The Panamanian military police came running when they noticed me among migrants in that secret camp and didn’t let me stay for long, demanding to know how I had found it and what I was doing there.

I finally met the Iranians face-to-face here in Golfito, where they told me about this. We met in another camp, this one maintained by the Costa Rican government. Under a bi-national agreement, the Panamanians catch “special interest aliens”, as American homeland security officials know them, and after a week or two have them bused straight to the Costa Rica border, where the government processes them, as I wrote yesterday and showed in a video, and facilitates their travel by bus to Nicaragua and eventually the American border. This policy was described to me as a humanitarian solution designed to suppress a dangerous smuggling industry in both countries and also to help the Americans somewhat filter for terrorists by providing opportunities to collect fingerprints and retinal eye scans. Until me, no American had interviewed the Iranians. Neither had any Panamanian or Costa Rican police or immigration official. So the Americans at the U.S. border will have their work cut out for them.

The English-speaking Iranian told me they were Sunni Muslims from the Kurdish part of Iran — one of the four claimed to be a recent Christian convert. He said they were all headed to the U.S. border and would claim political asylum.

Maybe they’ll achieve their asylum claims. But whatever happens, they’re all in for serious interrogations once they reach the American border; the fright will be on the other shoe this time. At issue for American intelligence personnel who will flock to whatever detention center they’re in, of course, will be determining whether they are Iranian intelligence agents, members of Hezbollah’s notorious Unit 910, or merely victims of a harsh Islamist regime and deserving of American sanctuary.

That’s a legitimate American responsibility with migrants from a place like Iran, and this shouldn’t be a hard concept to grasp because none of the four Iranians had any sort of identification with them, claiming various mishaps. The stories I was told as to why they deserve asylum seemed almost tailor-made to achieve credible fear from American asylum officers who will initially interview them: anti-government protest activity and the Christianity conversion thing, which could draw a death-penalty apostasy charge in Iran. But it’ll take hard-driving interviews above and beyond the asylum process to make sure of who these guys really are because it’s not as though our side can just call up the Iranians and ask for some database checks for involvement in crime, terrorism, or intelligence agency membership.

They Iranians said they got to Ecuador, which is a visa-free nation, then flew there from Iran and “from Ecuador to here, we travel illegally, border by border, country by country, until now.”

They claimed no smuggler helped them; they just figured out on their own what to do to this point. Of course, they wouldn’t need a smuggler to move through Panama and Costa Rica these days because both governments work hard and in concert to keep migrants moving north. The Costa Ricans were especially helpful: “They gave us a map” and a list of bus fare costs ($10 to $15) to another Costa Rican migrant camp where they could stay the night and from there pass into Nicaragua. It’s unclear whether the Nicaraguans are cooperating in this helpful facilitation toward the American border, but indications are that they are not participating.

As we bid farewell in the Golfito camp, the Iranians said they had their “permisos” to leave the camp. They left me then to walk into the small town down the road, where they could access Western Union. A “friend” in Ecuador was wiring the money and, in turn, that friend would collect reimbursement from their families in Iran. The money thing is complicated because of international sanctions and so forth, the English-speaking one told me.

The Iranians all were very curious about what would happen to them once the Americans get them in custody. All I felt I could tell them was that they should expect to be questioned.