How “straw purchasers” in the U.S. find a big bang for their buck for Mexico’s drug thugs

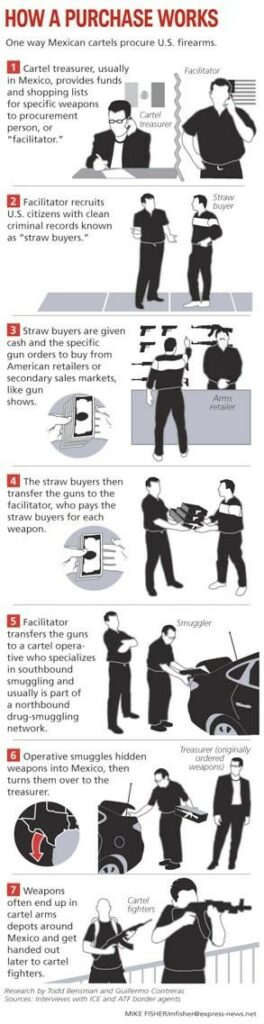

Crucial to the flow of guns into Mexico are networks of straw buyers — U.S. citizens with clean criminal backgrounds bankrolled by the cartels to shop for guns. Two kinds stalk South Texas: ordinary people with perhaps only a sneaking suspicion about who’s ultimately paying them; and those much more closely tied to cartels, perhaps even syndicate employees. Mexican officials say 60 percent of all guns purchased in the U.S. that make their way to criminals in Mexico were bought by straw purchasers. Straw purchasing, therefore, has become the new front – and maybe the only practical one – in an escalating bilateral push to shut down the pipelines.

San Antonio, TX — The young Mexican national looked over the table at a San Antonio taquería and nonchalantly described the firepower that passed through his hands as if he were describing the trowel he now uses to lay bricks.

Heckler & Koch MP5s. Colt AR-15s. M16s. Berettas. Barrett sniper rifles.

“To kill people, hurt people, we use them as a tool for kidnap and for escort drugs,” the former Mexican drug cartel foot soldier, who previously served in the Mexican army, said in broken English. “That was the use … that we gave to the weapons.”

To arm themselves, Mexican cartels pick guns like they would choose toys from a catalog and tap the plentiful supply in the U.S.

Crucial to the flow of guns into Mexico, where they are largely illegal, are networks of straw buyers — U.S. citizens with clean criminal backgrounds who are bankrolled by the cartels to shop for guns. Some rings draw in ordinary people lured by easy money from near strangers. Others are more closely tied to cartels through “facilitators” who might oversee a network of buyers.

Texas, by far, leads the nation as the primary source of guns for the cartels.

The former cartel foot soldier, for example, told the Express-News he got what he needed in Texas. He simply stated to the head of his 40-member cartel security unit — a feared paramilitary group known as the Zetas — what guns he wanted. The orders were passed to fellow cartel workers in charge of finding straw buyers who would be paid in cash or drugs.

“The people who was working here in the U.S. selling the drugs, they were the same that got the weapons,” said the former Zeta enforcer who is cooperating with U.S. authorities and asked that his name not be revealed for security reasons. “They get some people to buy the weapons, every kind of them, and then pay them for it. … Most times, we were better armed than the local police.”

Bang for the buck

Cartel-related killings in Mexico have doubled this year from 2007, reaching 5,376 as of Dec. 2, according to Mexican Attorney General Eduardo Medina Mora.

The U.S. is pursuing gun traffickers, and straw buyers in particular, like never before. More than 300 defendants were prosecuted in 2006 and 465 in 2007. Straw buyers include war veterans, college students, jail guards, grandparents and sons of lawyers; they get at least $100 a gun.

“Anyone who can legally buy a gun can get caught up in the scheme,” said Mark Siebert, resident agent in charge of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in San Antonio. “It’s college students, girls, guys, grandmothers. It’s anybody.”

In Houston, ATF agents uncovered one network of more than 30 straw buyers who spent more than $400,000 on guns, said J. Dewey Webb, agent in charge of the office there, which oversees San Antonio and much of south Texas.

“A lot of straw purchasers say, ‘Hey I’m not hurting anybody. I’m just making a few dollars,” Webb said. “But that AK killed someone in Mexico. It’s all connected and it’s all relevant.”

The U.S. and Mexico are, to some extent, cooperating more to track gunrunners, who often smuggle drugs as well. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement launched Operation “Armas Cruzadas” this summer. In June, similar bills co-sponsored by U.S. Rep. Ciro Rodriguez of San Antonio, Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchinson and others to expand the ATF’s Project Gunrunner were rolled into the Mérida Initiative, which makes $1.5 billion available so Mexico can combat drug trafficking, Rodriguez said.

“Mexico is Texas’ best trading partner, but we can’t let the drug cartels dictate our lives and hurt our efforts to work with our friends on both sides of the border,” he said.

“Anyone who can legally buy a gun can get caught up in the scheme,” said Mark A. Siebert, resident agent in charge of the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in San Antonio. “It’s college students, girls, guys, grandmothers. It’s anybody.”

In most cases, the buyer is not as innocent as he or she seems, Siebert said.

“In my years with ATF, I’ve never met an individual, either the straw purchaser or the facilitator, the person that’s financing it, who didn’t know they were doing something wrong,” Siebert said. “They may not know the exact violation, the exact statute, but everybody knows that what they’re doing is not right.”

Mexican officials, relying on information from their U.S. counterparts, estimate that 60 percent of all guns obtained in the U.S. and used by criminals in Mexico were bought by straw purchasers.

Cartels also exploit what is known as the “gun show loophole.” At gun shows, people not operating a business can sell their private collection of firearms without having to obtain information from the buyer, running an instant background check or even giving a receipt. The same is true for other parts of the resale market, like flea markets, ATF agents said.

Cartel figures can buy these used guns themselves. But they often send a straw buyer to licensed sportings goods stores and gun shops because from them they can obtain new, more glamorous guns in quantity.

The gun trade is one of the top foreign-policy issues Mexico plans to pursue with the Obama administration.

“Our focus has been to explore with U.S. authorities what could be done by law enforcement with legislation with this obviously illegal export of weapons to these organizations,” said a high-ranking Mexican prosecution official who asked that his name not be used for security reasons.

“Secondly, the emphasis has almost exclusively been to enhance the tracing of the guns. We need to go much further. U.S. legislation lets you go to the original dealer and first buyer only. The fact that no record has to be kept of that second sale leaves the trail cold until the gun ends up recovered in Mexico.”

By then, it’s already been used for murder.

“In my years with ATF, I’ve never met an individual, either the straw purchaser or the facilitator, the person that’s financing it, who didn’t know they were doing something wrong,” said Siebert of the ATF.

The cop killers

Celerino “Cele” Castillo of Pharr, Tx. might fit that description.

The former drug agent, a published author renowned for his daring do in Central America during the 1980s and early 1990s, recently lamented the turn for the worse his life has taken as he sat in a McAllen book store. He is packing up his McAllen area home in preparation for a three-year stay in federal prison for selling guns without a license.

“I made a major mistake, and I have great remorse for this,” Castillo said. “I did it to supplement my income, and here I am paying the price for it.”

There is no proof the 35 guns he bought through a straw purchaser he recruited and apparently used for cover ended up in cartel hands. But prosecutors say that can be surmised because many of them — 23 were handguns that can fire armor-piercing ammo — are favorites of the drug gangs.

Castillo admitted buying the firearms through Jay Lemire, whom he met at a gun show in San Antonio. During the investigation, Lemire, 38, told ATF agents that Castillo was filling orders from “backers” and that Castillo would pay him $250 to buy the guns.

Confronted by investigators, Lemire agreed to continue buying guns so agents could observe Castillo as he secretly handed over cash to Lemire, sometimes outside of gun stores or in the bathroom. Lemire pleaded guilty to selling firearms without a license and got five years’ probation. He declined to comment for this story.

But he told agents that Castillo made numerous comments about his backers having a hard time crossing the border to get all of the money for the guns to Castillo.

In interviews with the Express-News, Castillo disputed most of the accusations. Though he pleaded guilty, Castillo said he believes his gun prosecution is revenge by the U.S. government for uncovering a scandal in the 1980s.

“He had a reputation as an agent that really put himself out there,” said Michael Levine, who served in the DEA with Castillo and is the author of best-selling book, “Deep Cover.”

During an assignment in Central America in 1985, Castillo discovered cocaine was being smuggled to the U.S. from Ilopango Air Base in El Salvador by CIA operatives in a clandestine operation to help fund and arm the U.S.-backed Contras, which opposed the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, Castillo wrote in his 1994 book, “Powderburns.”

His assertions formed a piece in the puzzle of the Reagan administration’s Iran-Contra scandal. He took medical retirement in 1991 after being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The DEA said it doesn’t comment on former employees. Prosecutors and the ATF said they had not heard of Castillo before his arrest in March.

Castillo said he primarily bought guns for hunting that are hard to get in the Rio Grande Valley. But he admitted taking gun orders from buyers he would not identify, a circumstance that border agents describe as a tell tale sign of cartel ordering from Mexico of just the sort described by “Marcos.”

Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Roomberg said that of the 32 guns Castillo acquired, 23 were FN 5.7 pistols, known in Mexico as mata policias, or “cop killers.”

This has become the gun of choice of drug gangs in Mexico,” Roomberg told U.S. District Judge W. Royal Furgeson.

He could have bought guns himself because he is a U.S. citizen and had no criminal record, but he claims he paid Lemire to buy them because he wanted to help Lemire supplement his Social Security income.

“I told him, ‘Let’s buy some guns and resell them,’ ” Castillo told the judge. “I know it sounds like I’m making this up, but I’m not.”

That, however, doesn’t bear the ring of truth, ATF case supervisor Siebert said.

As a former law enforcement agent himself, Castillo had to have known the purchase of so many FN 5.7 handguns can electronically flag the ATF, who will track down the buyer and start asking questions. The fact that Castillo hired a straw buyer to purchase only cartel glamor guns suggests that he knew exactly what he was doing, except he didn’t get away with it.

Straw purchasing 101

As Castillo readies for prison, a generation less than half his age is learning the ropes.

Alejandro Palacios, 22, grew up in Brownsville, and moved to San Antonio shortly after his high-school graduation to further his studies. Here, he roomed with buddies from the Valley who studied at local colleges that include the University of Texas-San Antonio and San Antonio College.

A junior engineering major, Palacios is getting an education he won’t find in a textbook. He’s facing up to five years in prison for allegedly buying guns in a straw-purchasing scheme the ATF broke up earlier this year.

Palacios bought four firearms for Ricardo Garza and his older brother, Arnoldo, according to court records. The Garzas, who were contract security guards at the ICE-run Port Isabel Detention Center at the time, paid Palacios $150 for each gun.

“I couldn’t believe how easy it was,” Palacios told ATF agents of his first purchase, an AK-47 at a gun show in Live Oak.

He later went to gun stores. On the federal forms recording his purchases, Palacios falsely claimed the guns were for himself, which is how he ran into legal trouble.

He recruited Esli Garza, an ex-girlfriend, and one of his roommates, Hugo Garcia. The lure of $150 for each gun they bought was a powerful motivator.

“ ‘Yeah, I need the money,’ ” ATF agent Dan McPartlin quoted Esli Garza as telling Palacios. “ ‘I’d like to do that.’ ”

The group bought several FN pistols and semi-automatic assault rifles. One was found in Mexico.

On March 16, members of a cartel were involved in a shootout with Mexican soldiers in coastal Ciudad Madero, Tamaulipas.

The assailants slammed into an army truck, threw grenades and opened fire on the soldiers, who returned fire. The soldiers recovered several firearms, including a Bushmaster .223-caliber assault rifle. The ATF traced the gun to an Academy Sports and Outdoors store on Loop 410 near Vance Jackson in San Antonio.

Esli Garza bought the gun on July 10, 2007, for Ricardo Garza, court records show.

“I’m sure that the gun traffickers are smart individuals,” said Palacios’ lawyer, Eddie Bravenec. “The reason they choose people this age is that nobody will suspect them, and because these people are so young, (the traffickers’) chances of getting turned in is less.”

Cloaked in layers

As they do with running drugs, the cartels try to stay ahead of authorities. Pinpointing the facilitators is never easy if police can’t identify the straw buyers. That’s why authorities largely rely on gun retailers to be vigilant.

“It’s not like there’s a direct hand-to-hand (exchange) from somebody who comes into the U.S. and purchases the weapon to somebody high up in the organization,” said Jerry Robinette, special agent in charge of ICE in San Antonio. “There’s many, many layers and many, many people between point A and point Z.”

Ernesto Garza, 44, of Monterrey, Mexico, had nine people working for him in San Antonio and paid $100 to $600 per gun on top of the original purchase price.

He bought hunting guns here and sold them in Mexico, but later filled orders for high-power, high-capacity weapons that earned him a 100-percent profit in many cases. On the eve of trial this year, he pleaded guilty to buying more than 50 guns through straw purchasers and to smuggling the weapons across the border. He was sentenced Wednesday to 12 years in prison.

One of his straw buyers recruited six female friends. Sometimes, Garza paid the women directly, would tell them which guns to buy and occasionally accompany them to almost a dozen stores.

Two San Antonio gun shops — Dury’s Gun Store and Bass Pro Shops — turned ATF agents on to Garza’s straw purchasers after noticing they were buying FN pistols with cash on the same day or within days of each other.

In one instance, Garza used the same car that had transported 18 kilograms of cocaine to San Antonio to send back a shipment of guns to Mexico, typical of the method.

“We think the person sending the drugs and receiving the guns are the same,” prosecutor Roomberg said.

One of the FN guns was recovered in May at the scene of a gun battle that drug traffickers had with Mexican federal police in Xoxocotla, south of Mexico City. Two officers were killed. The gun was bought at Dury’s in August 2007.

Garza’s lawyer, Demetrio Duarte Jr., distanced Garza from the cartels.

“My client is not a member of any organized crime (ring),” Duarte said. “How those guns ended up in the hands of drug dealers, I don’t know.”

But according to the ex-Zeta enforcer who is now an informant, the cartels are usually behind the straw purchases and have little problem getting their hands on the weapons through layers of associates driven by greed. Their purpose is no secret: To kidnap, kill, “all kinds of stuff like that.”

“They never had any problems to cross them (the weapons) into Mexico,” the informant said of the cartel he worked for. “We knew about weapons, we just order. …We ask for the best weapons we could use for that work.”

Staff writer Guillermo Contreras contributed to this report