Human rights activists, migrant advocates, and the news media consistently cite extreme widespread violence and rampant government persecution of indigenous populations for Guatemala emigration to claim asylum at the U.S. border. Not in emblematic Yalambojoch. What drove people to evacuate this typical highland village was desire to send enough money home to build big houses like their neighbor’s, which makes them all ineligible for asylum.

By Todd Bensman as originally published February 10, 2020 by the Center for Immigration Studies

YALAMBOJOCH, Guatemala – The Domingo family’s long-term plan to send sons and daughters — small children at the time — to work in the United States when they grew up took root a decade ago, when a neighbor built an ornate mansion among the traditional mud-brick homes typical of this highland Guatemalan village of indigenous Mayan descendants.

Money from that neighbor’s son in the United States funded the concrete multi-story house, with eight bedrooms, gleaming tile floors, and faux-gold rimmed windows. And indoor plumbing too.

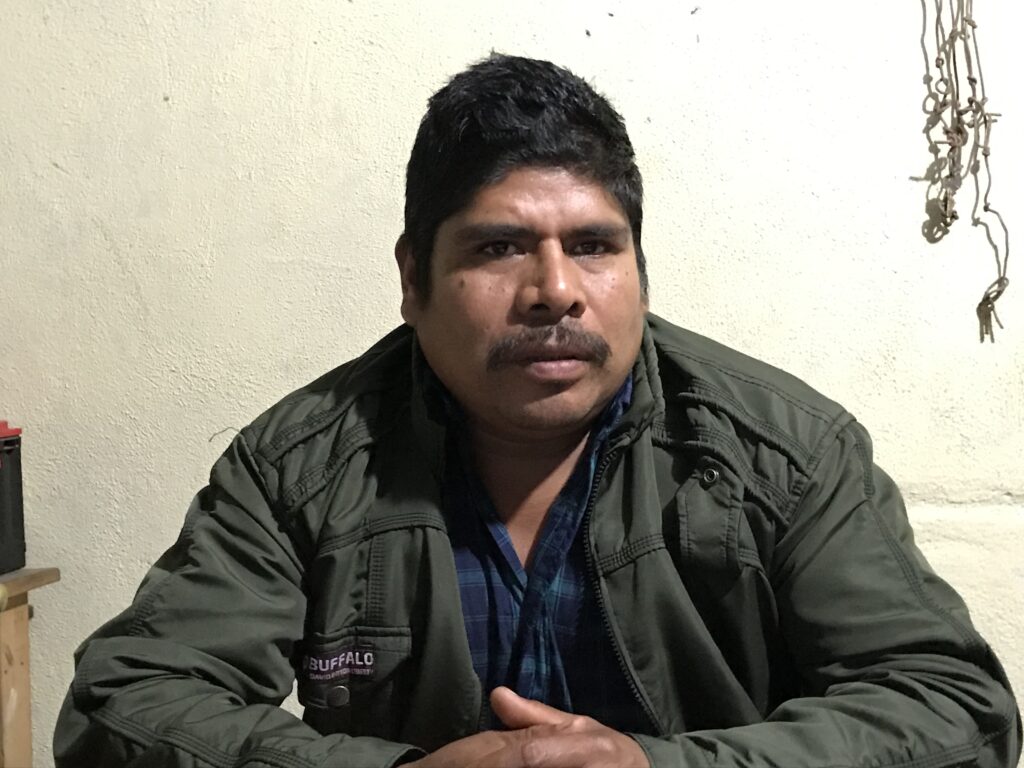

“I saw that — the big house — and I wanted the same thing. I wanted a big house for my family,” said Phillippe Marcos Domingo, 50, a subsistence corn and beam farmer who raised his extended family of five children in the austere traditional Yalambojoch mud-brick and wood-slat huts.

Now an American dream of sorts is going up on his children’s $2,000 monthly remittance money in the forms of two multi-story concrete houses of eight and nine rooms each that the families will live in when they return — just like that neighbor’s house and like many other houses in this tiny village. Hearing that bringing a child would enable quick release into the United States under a legal loophole, three of the Domingo offspring joined the exodus with Phillippe’s grandchildren and a teenaged nephew at the start of the mass 2018-2019 emigration, which left behind only an estimated 300 of Yalambojoch’s 1,500 residents, town officials say.

The Domingo family is hardly alone in its self-described motive for sending family members to work illegally in the United States. The desire for more house than needed as a common primary motivation stands at sharp variance with “push factors” most often cited to explain and justify the mass U.S.-bound exodus of at least 300,000 Guatemalans during 2018 and 2019, the majority of them indigenous peoples from this mountainous region known as Huehuetenango.

Human rights activists, migrant advocates, government reports, and the news media consistently cite extreme widespread violence, rampant government persecution of indigenous populations, along with poverty and hunger, climate change, and agriculture production dips.

But “house envy”, to build homes as big or bigger than your neighbor’s and far beyond basic sustenance? That one can be found almost nowhere in the ongoing policy conversation about illegal immigration. Part of that conversation now centers around a new Trump administration policy to deport a variety of migrant nationalities to Guatemala as a safe third country where they can apply for asylum. Critics insist Guatemala is too dangerous as proven by the mass emigration of its citizens

The “Primary Status Symbol Here”

This omission from popularized notions about illegal immigration is glaring. An online search turned up one brief reference to the otherwise rarely acknowledged social phenomenon, in an April 2019 article by Arizona Daily Star reporter Perla Trevizo, who wrote after visiting the region, that “everyone is leaving, planning to send money home to start buying food but especially to build the coveted concrete houses that are the primary status symbol here.”

A June 2019 blog by CIS Fellow Art Arthur, about the tragic drowning death in the Rio Grande of an El Salvadoran father and his child, pointed out that their motive was to raise money to build a house there and one day return to it. At about the same time, though, major U.S. media showed up in Yalambojoch in late 2018 and early 2019 to report about the death of a local child in CBP custody, whose father had brought him over the border already ill. Most, if not all, of the reporting referenced only that father and son had fled grinding poverty and violence and made no mention of local widespread aspirations of building modern houses.

The powerful, age-old human impulse to keep up with the Domingos, or outdo them, seems widespread in this half-emptied town of beautiful residences, a contrarian fact that can put lie to hundreds of thousands of U.S. asylum petitions filed by Guatemalans that inherently claim government persecution and imminent bodily harm.

Indeed, Yalombojoch Mayor Francisco Pais, Vice Mayor Pedro Garcia, and every villager interviewed during a two-day visit in January told CIS that violent crime was nonexistent, so absent in fact that police are not necessary; informal local civil patrols take care of any petty crime issues. Government persecution hasn’t occurred in decades either, they said, not since the civil war that ended in the 1990s. The nearest government office source of possible persecution, Mayor Pais pointed out, was a five-hour drive away.

“This is a really quiet and calm place,” Mayor Pais said. “The problems of gangs and criminals don’t happen here. It’s not the same here as in other places.”

No, he explained, the main reason his town lost so many of its residents was because “People see other people building the pretty houses, so they want to go too,” he explained. “They work for four or five years and then they come back and live in them.”

Housing greed as a driving force behind U.S. immigration also is indicated throughout the surrounding Huehuetenango province. A drive though Huehuetenango reveals the same brightly colored, multi-story modern homes popping up like mushrooms in village after village, town after town.

From the perspective of Americans who live in modern urban economies, those villages and Yalambojoch might be judged — and frequently are — as impoverished and backward. But that’s a view through western lenses, perhaps politically convenient. Seen anthropologically, however, these are traditional indigenous communities where generations have always lived proudly and independently as pastoralists, from the land. Many residents speak the Chuj language, unwilling even to learn Spanish, and farm their needs from small plots of land.

Western ideals like fancy housing penetrated with globalization, returnees from earlier smaller emigrations, internet access, and cell phones; a singular feature of Yalambojoch is the tall antenna in the center of town connecting local culture to the modern outside world and its ideas about prosperity.

When someone built the first big house in 2000, the virus of western want and desire spread quickly, fueling departures in the following years, funding more such houses, and a cycle that escalated when everyone discovered the United States would quickly release into the country anyone who showed up with a child, under the Flores loophole.

“Happy and Calm Now Because I Have this Big, New House”

Angelina and Francisco Santizo sent a 20-year-old son to the United States on the new migration wave out.

The main reason?

“A lot of people started to see a lot of people going to the U.S. starting to build big houses, and we wanted the same,” said Francisco, a subsistence bean and corn farmer like his ancestors.

Santizo said his son went alone, without a child, claimed political asylum at the border, and then was allowed in legally to pursue it. Not provided for in current American asylum law is the apparent motivation he described:

“When my son was growing up, we saw that everyone was building houses and when my son grew up, he said to us, ‘I’m going to go to the U.S. now so I can send you money to build a house too.'”

For several generations, the Santizo family has lived on a plot of land in the standard wood and mud-brick dwelling. The couple continues to live in the home, subsisting on food they grow and animals they raise, while slowly constructing the massive new three-story concrete edifice just feet away on money the son sends every month.

“I feel happy and calm now because I have a big house. I’m really glad to have this — and proud,” Francisco said.

Like other families, the Santizos believe their son will return in a few years to live in the house with them and raise a family while also subsistence farming like their ancestors always have, more testament to popular feeling that Yalombojoch is neither dangerous nor gripped by famine.

Four families told CIS they were spending in the neighborhood of $35,000 to $40,000 for their homes, mostly material and labor since they already owned the land.

Several families living in their traditional dwellings next door told CIS they, too, want the new houses but had no one extra to send, or they would have done so. Many of the departed had to pay or borrow thousands of dollars for smuggling fees that others didn’t have and couldn’t get.

“You can see a lot of people are building a house, and I would really like one too,” said Rosa Marcos who lives in a tin-roofed wooden house with her husband and mother-in-law, a wood-burning fire pit its interior centerpiece. Several large houses loom over this family’s dwelling.

Marcos said she feels frustrated by the inequity, but that “we don’t have the money to pay for the trip. I can’t get the money.”

Not Yet in the Public Discourse

Academic experts in Latin America migration acknowledge that house desire can be a primary motivation for emigration to the United States.

Sara Lynn Lopez, associate professor of architecture at the University of Texas-Austin, has studied remittance house-building for 15 years and is author of “The Remittance Landscape”.

She said her research and that of a small number of other academics clearly shows that thirst for large houses is a primary impetus for emigration to the United States, especially in Mexico, but also in Guatemala.

“It is definitely one of the findings, that it [housing] is an impetus for migration. It absolutely is one,” Lopez said. “That is definitely something that people would completely agree on, and there’s evidence to back it up.”

But she also is puzzled that this immigration push factor “hasn’t reached popular discourse yet.”

“I’ve been researching for 15 years, and it’s always kind of amazed me that I didn’t start seeing articles that even referred to it — even a little bit — until the last two years.”

Professor Nestor P. Rodriguez, an immigration studies expert also at UT-Austin who has traveled extensively through Central America for research, agreed that “Your observation is correct, that building homes is a big status symbol.” Not only is the quest for big-house status an important motivation for immigration in Guatemala and Mexico, he said, but researchers also have found evidence of it in Vietnam and China.

Rodriguez said he believes the absence of public discussion about this cause from Northern Triangle countries is because it has never been systematically studied from that angle.

“It’s not part of the debate because research hasn’t told us yet how prominent this home construction is as a motivation yet,” he said. “We have yet to measure this.”

Wrong Diagnosis, Wrong Medicine

Identifying and understanding the true push factors behind mass migration is important to formulating American policy responses to it. It seems clear that prognostications are at least partly wrong about Guatemala, on both sides of the U.S. political divide.

Even Trump administration officials have cited “food insecurity” as a key push factor informing decisions to travel from Guatemala, “where we have seen the largest growth in the migration flow this year (2018)”, according to then-CBP Commissioner Kevin K. McAleenan.

But if the prognosis is wrong, then so too would be any prescriptions.

For instance, critics of a Trump push-back policy to force Mexicans to apply for asylum in Guatemala would gain no political traction by acknowledging that bigger houses, not mass government persecution and widespread violence and hunger in that country, was what had actually driven hundreds of thousands to the U.S. border.

One of the more prominent proposals, based on the violence-persecution-poverty narrative, is a massive infusion of U.S. development aid, like the Marshall Plan for post-World War II Europe.

Also, if bigger houses are the real motivator, then the probabilities of large-scale asylum fraud increase by magnitudes. More than 615,000 asylum claims were logged in just 2019, one of the top nationalities in recent years consistently being Guatemalans, according to Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) statistics.

U.S. Border Patrol agents, asylum adjudicators, and immigration judges should know to ask about quests for bigger houses instead of violence and government persecution when considering probably fraudulent Guatemalan asylum claims of government violence.

People in Yalambojoch like Consuelo Jorge Domingo don’t pretend there is any other reason for their loved ones to have departed a village so safe and sustaining that they are willing to invest in its long-term future.

Working in a tiny convenience store, Domingo said her husband went to the United States and applied for asylum like everyone else. Not to escape anything terrible in Yalamojoch but to get one of those big houses everyone else has. His parents and relatives are building it right now across the street from the store.

Blue tiles and window and door dressings adorn the massive two-story house. As money comes home, construction advances, little by little. Domingo feels sad she and her eight-year-old daughter must live without him for so long, but the feeling is somewhat offset by the sweeping house going up across the street that they will all live in soon when he returns voluntarily to live in the village they all love.

“We wanted a big house for our family like everyone else is building,” she explained of his departure. “It will be finished soon, and then he will come home and live in it with us.”