By Todd Bensman as published by the Center for Immigration Studies on April 30, 2019

New reports keep piling up that asylum seekers and refugees from terrorism-spawning countries have slipped through the U.S. vetting systems despite records of Islamic terrorism. Like episodic idiot-lights on the car dashboard that briefly blink on and then disappear for a while, news reports slowly raise the idea that something is wrong with the system. Somali, Iraqi, and Palestinian Arab refugees and asylum seekers, with terrorism histories they want to hide, keep getting through supposedly advanced security vetting systems put in place after 9/11.

Few outside of intelligence and law enforcement circles — and perhaps not even those inside the circles — really know the actual extent of vetting failures that grant legal status to those hiding terrorism involvement. One tally found an entirely unacceptable 13 cases of vetting failures involving actual terrorists caught or killed between 9/11 and April 2018. But the numbers are undoubtedly higher, accounting for cases where the liars just haven’t been made public yet or there was strong terrorism intelligence rather than some sort of conviction under terrorism statutes or attack.

While serving as a counterintelligence manager, I can say I was aware of one especially egregious case involving an ISIS beheader who was eventually deported in a case that was never made public.

One thing is for sure: New public discoveries of vetting failures are constantly growing the stack. Each new one makes it clearer than the last that the United States is suffering a security problem of undiagnosed proportions. One or especially 13 is far too many when considering the consequences that just 19 improperly vetted al Qaeda terrorists wrought on 9/11 with their U.S.-issued visas.

Following are some recent public cases. These should serve as reminders to voters, policy-makers, and adjudicators at the State Department and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services that so-called “extreme vetting” should remain a national priority goal. It also wouldn’t hurt to expand the number of countries on President Trump’s so-called “travel ban” list (as I have advocated) until the vetting problem parameters are mapped out and understood.

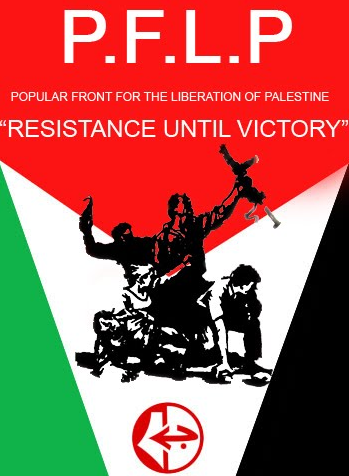

George Z. Rafidi, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

Texas resident George Z. Rafidi, a Ramallah-born Palestinian Arab living and running businesses just this side of the Mexican border in the Lone Star State’s Rio Grande Valley, is a case in point. Cameron County law enforcement and the FBI recently raided Rafidi’s home and businesses, charging him and associates for allegedly operating illegal “eight-liner” slot machine casinos. The raids got a few localized headlines. But underground casinos are not the story with Rafidi. He has been living in the United States for nearly 20 years with a terrorist background doing who knows what beyond running slot machines.

Since April 2018, Rafidi has stood federally charged with covering up his terrorist activities on applications for asylum in 2000, lawful permanent residence in 2003, and U.S. citizenship in 2012. He successfully gamed the system all three times, according to court records, when it seemed the briefest of due diligence checks at any point would have rolled up Rafidi.

Federal court records allege that Rafidi, after flying to the United States on a tourist visa in 2000 and overstaying it so that he could claim asylum, criminally failed to disclose that he served as a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) from 1994-1996 and also that Israel in 1997 had convicted him of membership in an illegal group and brokering a weapons purchase. The U.S. State Department designated the PFLP a terrorist organization in 1997 (following a 1995 designation by executive order) after years of involvements in airliner hijackings and suicide bombings, kidnappings, and murders in Israel to the present day.

Israel gave Rafidi an 18-month prison sentence but freed him later in 1997 after only four months as part of one of its many prisoner exchanges.

Court records don’t address how any of this history got past American asylum application adjudicators from 2000 to January 2, 2002, when Rafidi was awarded asylum. But they do say that in 2000 he offered a plausible-sounding obscuring claim; he only told American asylum officers that he’d thrown rocks during the Intifada uprising, had been imprisoned on a false charge of membership in Hamas, and was at risk of further persecution by Israel for his election to the student body leadership at Beir Zeit University.

The asylum officers just bought it, when a quick check with friendly and cooperative Israel during a standard background investigation, at any point up to his 2002 asylum grant, almost surely would have turned up the disqualifying PFLP activity, even if all of this occurred during a time of less vigilance.

More baffling is that, according to the government indictment, Rafidi got away with the same lies and omissions — and much more — during the most vigilant times after 9/11. Rafidi flew under the radar in 2003 when he applied for lawful permanent residence, and then again in 2012, when he applied to become a naturalized U.S. citizen. Nobody apparently bothered to even check basic criminal history. Had that been done, it would have been discovered that, In 2001 and in 2002, Rafidi was arrested and convicted for misdemeanor shoplifting and for felony theft in Texas, both potentially disqualifying events. For the felony theft charge, Rafidi was sentenced to three years’ probation.

To get away with it, all he apparently had to do was check the “no” box on his 2003 permanent residence application on the question for whether he had ever been charged, convicted or jailed for any reason inside the United States, as well as if he had ever belonged to a terrorist organization.

There was plenty of time to check; Rafidi got his green card about four years later, in 2007.

He washed, rinsed, and repeated it all again in 2012 for his U.S. citizenship application, but with even more falsifications. By 2012, Rafidi had been caught and detained traveling south over the Gateway International Bridge in Brownsville, Texas, for failing to declare $28,995 in cash. Why he was moving that kind of cash into Mexico and not declaring it is a very good question left unanswered in court filings. But he also had gotten caught up in a bank fraud investigation involving a home loan and the purchase of a Bentley.

On his naturalization application, filed in Texas, Rafidi falsely swore he still had never been detained inside the United States (the Brownsville port of entry detention and the two theft cases), or had been charged with a crime for which he was not arrested (the bank loan case). That was in addition to the old claims that he had never been arrested in a foreign country, or held membership in any organization, fund, party, or association deemed a terrorist group. He also falsely claimed that he had been born in “Jerusalem” rather than Ramallah.

Finally, an immigration officer interviewing Rafidi in Cameron County, Texas, earlier this month about his naturalization application put an end to the masquerade.

Mahmad hadr Mahmad Shakir, a.k.a. “Vallmoe Shqaire”, Palestine Liberation Organization

“CNN Investigates” reporter Scott Glover deserves credit for an eye-opening report published last week, titled “How a convicted terrorist became a US citizen”. The similarities to the Rafidi case inescapably raise questions as to whether American adjudicators have some sort of blind spot when it comes to Palestinian Arab applicants and a seeming inability to pick up a phone and call Israel.

The CNN report, as well as court records and a Department of Justice press release, revealed how Shqaire, a Palestinian with Jordanian citizenship who had been living in Los Angeles, Calif., got into the United States on a visitor’s visa in 1999. It would not be discovered for nearly a decade that his real name was Mahmad hadr Mahmad Shakir. That same year, he paid $500 to a woman to marry him, a so-called “green card marriage” that didn’t work out. But he was then able to apply for and successfully obtain legal permanent residence, and eventually obtained citizenship.

To do so, he had to illegally omit the disqualifying facts of his life history and make sure no one had his real birth name. Among these was that Israel had convicted him as Mahmad hadr Mahmad Shakir in 1991 for a plot to blow up a civilian bus for the Palestine Liberation Organization’s violent “Shabeba” cell. Shqaire’s work in the Shabeba cell also required that he train with all sorts of arms and explosives and that he beat Arabs suspected of collaborating with Israel. One of those victims died of stab wounds.

The CNN report was unable to establish what, if any, post-9/11 background investigation protocols were followed for his legal permanent residence and citizenship application processes.

Perhaps one clue is that even seven years after 9/11, U.S. immigration officers seemed inclined to simply take Shqaire at his word. CNN reported that the U.S. immigration officer who handled his citizenship application said she merely relied on him to “provide complete and truthful answers” about his criminal past and associations. Only if he had told the truth about his bombing conviction would she have requested further documentation. Short of that, she approved his application in 2008.

CNN quoted a former U.S. immigration official involved in the vetting process in 2008 saying that a mandatory background check in place at the time should have detected the terrorism conviction, whether or not an applicant disclosed it. But left unclear was whether the check took place or, if so, was defeated by the false name. A check of his fingerprints with the Israelis would later lead to his undoing.

Shqaire enjoyed his American citizenship for the next decade, even after he got embroiled in a credit card fraud investigation in 2010 and confessed to federal agents that he had been jailed by the Israelis twice. Counterterrorism investigators kept on the trail, in part because Shqaire had been sending cash proceeds overseas for unknown purposes. By 2013, they were able to get a fingerprint match, then retrieved and translated Israeli court records related to the 1991 conviction.

Shqaire now stands convicted of lying to USCIS officers when he swore he had never been arrested, convicted, or sentenced for any crime, and was never a member of any organization or association. He’ll be deported after he serves his sentence, which has not yet been set.

“By repeatedly lying to USCIS Officers, defendant sought to conceal his extensive and violent criminal history in Israel and attacked the immigration safeguards that are in place to protect persons like the defendant from entering our country,” prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memo.

Mohamed Abdirahman Osman and Zeinab Abdirahman Mohamad, al Shabaab

I’ve already written about Tucson, Ariz., refugees Mohamed Abdirahman Osman, 28, and Zeinab Abdirahman Mohamad, 25. But this case bears mentioning again. Osman and Mohamad are an Ethiopian couple with several children who filed refugee applications in 2013 at the American embassy in Beijing, China, claiming they were Somalis (because, unlike Ethiopia, Somalia has no checkable intelligence records on its terrorists). The whole family was living as legal permanent residents, thanks to a completely bogus cover story, until Osman and Mohamad were arrested in 2017 and it all came unraveled.

According to court records, it turns out the couple and their extended families all had been enmeshed with the Somalia terrorist group al Shabaab, rather than fleeing the group’s wrath as they falsely claimed to American embassy officials and later to U.S. immigration authorities as they applied for citizenship. Mohamed Osman allegedly lied about how an explosion blew off his hands and partially blinded him; it happened while he was operating for al Shabaab. He also conveniently left out the fact that he sent as much as $32,000 to family still active in al-Shabaab, including to a brother after the brother went on the lam following his conviction, along with an uncle and aunt, for carrying out a deadly May 24, 2014, restaurant bombing in Djibouti.

Conclusion

These three cases have lots of company. In Chicago, just 24 months ago, another Palestinian Arab recently pleaded guilty to having illegally obtained her U.S. citizenship by covering up her 1969 Israeli conviction for two 1970 fatal bombings. Rasmieh Odeh, 69, came to the United States on an immigrant visa in 1994 and then obtained citizenship 10 years later in 2004, well after 9/11 security protocols went into effect.

Let’s also remember the August 2018 case of the Iraqi refugee resettled in California who was discovered to have murdered police on behalf of ISIS, or the 2011 arrests of two Iraqi refugees in Kentucky who planted IEDs to kill American soldiers in Iraq and plotted in the United States to send weapons to their former terrorist comrades. We can see these cases blinking at us like idiot lights on the car dashboard.