Europe’s tragic experience with refugee resettlement from Muslim-majority nations holds lessons for American homeland security strategists and policy-makers, especially the extent to which security vetting is incorporated as a central component in any national strategy to manage border-crossing migrants arriving as strangers without identification at the U.S.-Mexico border.

By Todd Bensman as originally published August 19, 2020 by the Center for Immigration Studies

An Iraqi asylum seeker thought to have radicalized while living in a Berlin refugee center “purposefully hunted” motorcyclists in a Opel Astra sedan this week, crushing two riders Tuesday and severely injuring three passengers in another car while bulldozing one of the motorbikes into it, according to press reports coming out of Germany. No one immediately died, thankfully, though one of the cyclists was in critical condition fighting for his life this week.

The 30-year-old Iraqi identified as “Sarmad A.” gave German anti-terrorism investigators plenty of reason to initially conclude he harbored an “Islamist motive” for the attack, despite past psychological treatment. Initial reporting had it that Sarmad allegedly shouted “Allahu Akbar” during his attack, laid a prayer rug on the street and began praying afterward, and maintained a Facebook page where he supported ISIS and seemed to foretell that he planned to become a martyr in a way that involved a car.

The Berlin vehicle-ramming (a tactic frequently recommended by ISIS and Al Qaeda) extends a run of jihadist attacks and plots by migrants resettled in a dozen European countries among some three million refugees from the Islamic world since the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 and the early Syrian civil war years.

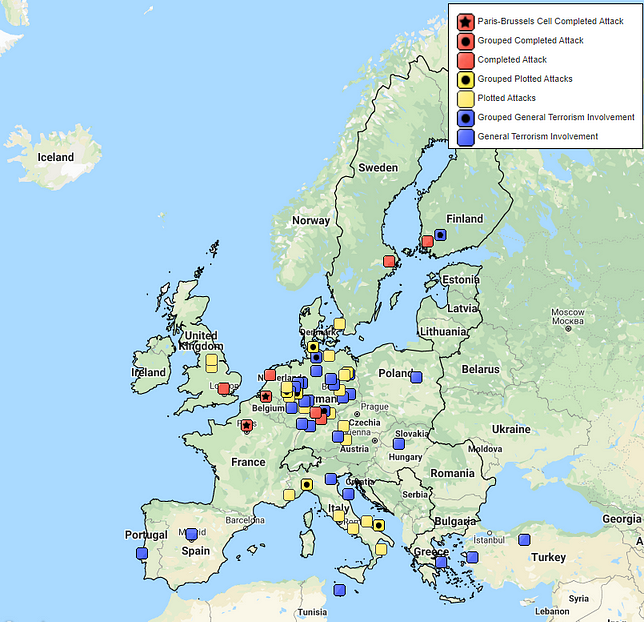

This week’s Berlin attack also adds to Center for Immigration Studies research on the phenomenon published in November 2019, which quantified the attacks through 2018 as evidence of a new global terror tactic: terrorist border infiltration and abuse of asylum systems. The CIS study found that between 2015 and 2018 alone, at least 104 border-infiltrating Islamic extremists from Muslim-majority countries like Iraq attacked, plotted, or successfully hid from European asylum adjudicators their past terrorist group memberships and atrocities.

Europe’s tragic experience with refugee resettlement from Muslim-majority nations holds lessons for American homeland security strategists and policy-makers, especially the extent to which security vetting is incorporated as a central component in any national strategy to manage border-crossing migrants arriving as strangers without identification at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Since the 2018 end of the CIS study period, scores more migrant-terrorists who came in over Europe’s borders as supposed refugees have attacked or were arrested while plotting mass-casualty and smaller-scale attacks.

For instance, as I reported for CIS in May, Spanish police arrested one of Europe’s most-wanted terrorists, Egypt-born Majed Abdel Bary — the so-called “ISIS rapper” — after he posed as an asylum-seeking migrant this year, traveling from Syria to North Africa and hiring a smuggler in Algeria to ferry him across the Mediterranean Sea on a wooden “patera” boat. Authorities found him after just five days, plenty of time for this particular proven jihadist killer to have done some damage.

In April, German anti-terrorism police rounded up five Tajik asylum seekers, ranging in age from 22 to 32, as they allegedly were about to attack two U.S. Air Force bases. The five apparently “all entered the country as refugees” and had been on intelligence radars for some time. (So, too, was Sarmad A.) All applied for political asylum, which afforded them time to form a cell and to stockpile automatic weapons, ammunition, and the components for anti-personnel explosives to kill U.S. soldiers.

France, which has suffered the attacks of migrant-terrorists almost as much as Germany, took another one in April when a Sudanese migrant asylum-seeker went on a stabbing spree and killed or wounded half a dozen bystanders in the name of jihad. He, too, was arrested while praying.

Even though the height of Europe’s migrant crisis pretty much ended in 2017, those who came in before then and after keep attacking. Far too many to discuss here.

But the French newspaper Le Parisien, in covering the latest German attack, noted that German authorities have foiled a dozen attempted vehicle-ramming attacks since an infamous December 2016 one by an asylum seeker who drove a truck over 12 people at a Christmas market, including two in November 2019. And there was a thwarted “biological bomb” attack in June 2018 by a Tunisian linked to ISIS. Since 2013, the number of Islamists considered dangerous in Germany increased five-fold to stand at 680 at the moment. The number of Salafists is estimated at 11,000, twice as many as in 2013, Le Parisien reports.

“German Chancellor Angela Merkel has often been accused, especially by the far right, of having contributed to these attacks by generously opening her country’s borders to hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants in 2015,” the paper concluded.

Attributing the security concern about strangers from terrorist-rich countries solely to the so-called “far right” suggests that no one else on the political spectrum shares it, even in the wake of actual bloodshed, real funerals, expensive security arrangements in European cities, and terrorism trials that send migrant-terrorists to authentic prisons.

If it is true that only the “far right” still thinks about such matters, then it is also true that this is what led to Europe’s tragedy in the first place. And probably will, eventually, to something like it in the United States.