This case undermines criticism that President Trump’s “Travel Ban” wrongly blocked U.S. entry of doctors from Muslim-majority countries on the temporary work H-1B visas. The case also is cause for reassessing current vetting in unlisted countries, to ensure threats are not imported among the doctors and other skilled professionals who use the visa. Finally, the American public, elected leaders, and security professionals should never assume that force fields of credibility immunize doctors from security investigations and thorough vetting.

By Todd Bensman as originally published by the Center for Immigration Studies on May 4, 2020

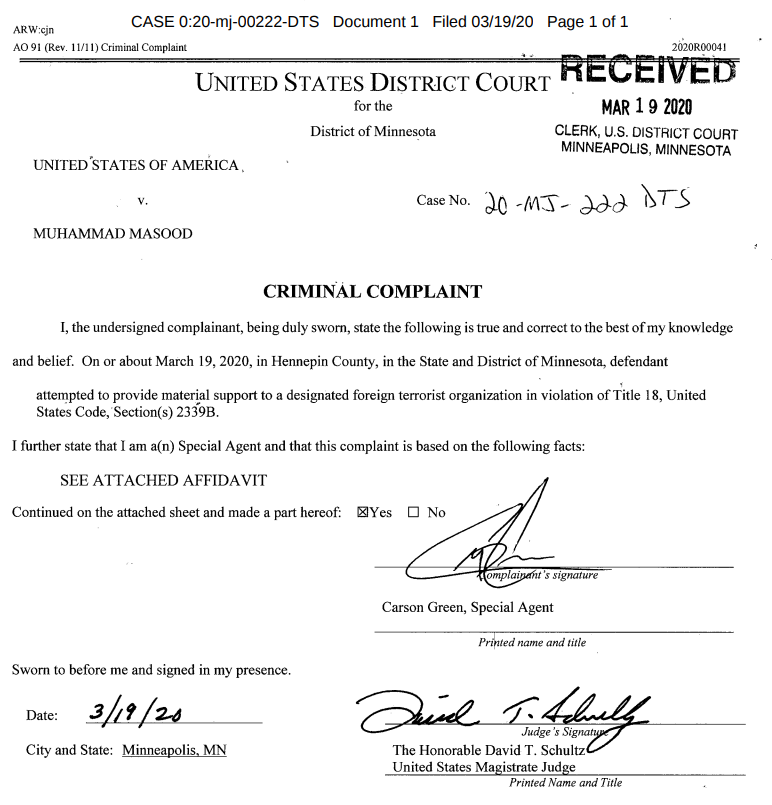

During his two years working as a “Research Coordinator” on an H1-B visa for the Rochester, Minnesota Mayo Clinic, Pakistani medical doctor Muhammad Masood allegedly saw himself as having gotten “behind enemy lines where not many people can’t even reach here to attack.”

A federal criminal complaint almost lost in the nation’s Corona-19 virus crisis alleges that Dr. Mohammed Masood planned from the day he arrived in America on his H1B visa in February 2018 that he would use the rare access it afforded to learn something useful about his enemies, the better he could attack out of perceived religious duty. By January and February 2020, the 28-year-old was messaging on the encrypted platform about how sick he had grown of smiling every day at the “passing kuffar,” a derogatory term for non-Muslims that often justifies execution. All the smiling was “just to not make them suspicious…I cannot tolerate it anymore.”

He messaged that he could not let his H-1B visa go to waste. “Sometimes I wantto (sic) attack enemy when I am behind enemy linea (sic) itself,” he messaged on an encrypted communications platform in January. “I wonder if I will miss the opportunity of attacking the enemy when I was in the middle of it.”

By the grace of an undercover FBI investigation, Masood will do no such thing. Agents arrested Masood on March 19. By then, he had changed the plan from attacking the local kuffars he hated so much to joining ISIS in northeast Iran and Afghanistan, or in Syria as a medic, or maybe engineering drones “and also fight.” It’s unclear why he changed his mind about attack on U.S. soil.

“You know, brother, there is so much I wanted to do here… lon wulf (sic) stuff you know…but I realized I should be on the ground helping brothers sisters kids inshallah.” (sic)

The Pakistan-licensed doctor was as deficient in operational security as he was in spelling English. The individuals on the other side of his encrypted communications were undercover informants for the FBI who kept asking if he was absolutely sure he really wanted to quit his Mayo job and join the ISIS fight overseas.

“I want to kill and get killed…and kill and get killed… and again and again. This is what …Allah wished.”

He now stands charged with attempting to provide material support to a designated foreign terrorist organization, the crime usually used for those hoping to join ISIS. Masood went so far as to quit his Mayo job, auction off his personal belongings and purchased an air ticket to Jordan. But Jordan closed its borders as part of its Covid-19 lockdown strategy, so Masood decided to catch a cargo ship out of Los Angeles. FBI agents busted him in the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport as he went through the TSA screening line.

The Massod case raises a number of issues that ought to be debated as matters of public policy and homeland security. For one, this case undermines criticism that President Trump’s “Travel Ban” wrongly blocked U.S. entry of doctors from Muslim-majority countries on the temporary work visas. As well, the case is cause for reassessing current security vetting protocols in countries not on the travel restriction list, to ensure that hot security threats are not imported among the doctors, engineers, other skilled professionals who use the H-1B visa to leave countries of national security interest. And lastly, the American public, elected leaders, and security professionals should never assume that force fields of credibility immunize doctors from security investigations and thorough vetting. They don’t, as we well learned from Dr. Nidal Hassan’s massacre at Fort Hood, Texas in 2009 and rom a bizarrely long list of other Hippocratic Oath breakers to be described shortly.

Masood would not obviously have stood out as someone who might flag on risk profiles for terrorism, even though he was born, raised and educated in the country where Osama bin Laden found years of safe harbor until Navy Seals killed him in a clandestine raid. His LinkedIn profile had him earning a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery from Riphah International University. He earned a General Certificate of Education from the University of Cambridge and held a license to practice from the Pakistan Medical and Dental Council.

Undermining Critics of Trump’s “Travel Ban”

H1-B visas allow millions of non-immigrant foreigners to work temporarily in the United States, in skilled jobs for industries and big businesses that vouch for their need of the workers and are willing to sponsor them. The visas are renewable, their holders often hoping to parlay them into more permanent green cards and long careers in America.

The U.S. tech industry is the most prolific employer of H1-B workers, especially Indians over the past decade or so, but the health care system is right up there, claiming shortages of skilled American workers. Masood would have been among 1,871 Pakistanis who applied for H1-B visas in 2018, among a total of 419,637 that fiscal year. The medical and health sectors hired more than 185,000 of all nationalities between 2007 and 2017.

Medical centers like Mayo like hiring foreign medical school graduates like Masood to work high-volume hours, and they clamber for research jobs with name-brand clinics in a desperate hope to snag a highly rare and valuable residency spot, which almost guarantees a prosperous American life; indeed, Masood’s LinkedIn site openly described himself as a “Residency Aspirant 2020!”

The Masood arrest undermines critics of President Trump’s travel restrictions on Muslim-majority nations, some of whom have explicitly complained that it has blocked foreign-born physicians from, initially, seven Muslim-majority countries (Pakistan not among them) on the travel-restrictions list. For example, a 2017 New York Times report quoted medical establishment figures lamenting that Trump’s “travel ban” had blocked thousands of desperately needed foreign physicians (like Masood) who, if they could achieve the requirements, would work in underserved small towns and poor urban neighborhoods that American doctors eschew as not lucrative enough.

More than 15,000 doctors from the seven Muslim-majority countries were covered by Trump’s restrictions, including 9,000 from Iran, 3,500 from Syria and 1,500 from Iraq, The Times reported.

But the Times story and critics, oddly, never seem to address obvious homeland security concerns like vetting such visa applicants for security.

And those critics should finally have to address the Masood case and many more besides.

Doctors of Terror

Maybe it’s time to start adding professionals like foreign doctors applying for U.S. medical positions to risk profiles from all countries of national security concern, which would trigger deeper-dive investigation for H-1B visa applicants in countries like Pakistan.

The idea is not far-fetched when considering research-based evidence and other anecdotal reporting that medical doctors all-too-often become terrorists or terrorist leaders. There’s Bin Laden’s successor Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri; George Habash, who founded the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine; and Fathi Shikaki, founder of Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Abdel Aziz al-Rantisis, the late leader of Hamas was a pediatrician.

Doctors are not just terrorist leaders but operators too. Eight suspects in the 2007 foiled so-called “Physicians Plot” to bomb London and Glasgow targets were physicians and medical professionals, such as the Iraq-born Dr. Bilal Abdullah arrested trying to blow up a jeep packed with gas cylinders at the Glasgow airport.

U.S. Army Maj. Nidal Hassan, the jihadist who massacred soldiers at Fort Hood in 2007 was a doctor. The American-educated “Lady al-Qaeda,” Pakistan-born Aafia Siddiqui is now in federal prison in Texas after a 2010 conviction for grabbing an M-4 rifle after her American capture in Afghanistan and opening fire on U.S. soldiers, screaming “Allah Akbar!”. She was an M.I.T.-trained neuroscientist who earned a PhD from Brandeis University and went on to plot mass-casualty attacks on several New York City landmarks.

In 2015, ISIS put out a call for foreign health workers through social media, blogs and high-budget videos boasting of state-of-the-art facilities and equipment and medical schools in which 100 students were allowed to train for free (half of them foreigners.)

Doctors and medical students responded enthusiastically and came running for the opportunity from the UK, Canada, the United States and other countries. One of them was Dr. Kefah Basheer Hussein, a doctor of rheumatology who served ISIS and its predecessor incarnations for 15 years, according to CNN, which interviewed the captured physician in 2018. He both killed and healed as ISIS Minister of Health. But Dr. Hussein also oversaw organ and blood harvesting from captives scheduled to be executed.

Security Vetting

A friend of mine who administers a medical school and hospital complex in the U.S. Southwest, and did not wish to be quoted by name, told me the facilities that bring in foreign medical students on the H-1B visas from the Muslim world do no security vetting on their own and rely instead on the federal government to do that work.

“We might run drug tests or something with criminal background but the assumption is that the government has done that job,” he said.

Because they are non-immigrant temporary workers, H1-B applicants go through about the same security screening as would a foreigner wanting to enter on a tourist visa, even in countries of national security concern like Pakistan, which is regarded as a “high-threat” post.

Federal officials familiar with the vetting process tell CIS that DHS and the State Department will check the application packet for obvious signs of fraud and run applicant names and dates of birth through TECS, CLASS, and IDENT databases for hits on terrorism watch lists or criminal history. Fingerprints are run through other databases. The packet is passed to an in-country U.S. consular officer, who will call the applicant in and conduct a perfunctory, pro-forma interview looking for signs of fraud or inconsistency. The same checks typically are run on anyone asking for a short-term tourist visa, even in countries like Pakistan where U.S.-designated terrorist organizations operate.

“It’s the same amount of vetting as to go on vacation at Walt Disney World,” one DHS veteran explained.

With no database hits, paperwork in order and checking out, and no suspicions of fraud, said one officer of the U.S. State Department familiar with the process, “the consulate officer probably said, ‘oh, he’s a doctor… he’s going to the Mayo Clinic…this packet is probably ok…um great, go save lives!”

In 2019, the Trump administration wisely moved to toughen vetting for all foreign visa applicants by requiring five years’ worth of social media profiles, email addresses, phone numbers, international travel, and deportation status, as well as whether any family members have been involved in terrorist activities. Data like that might have opened more vistas on visa applicant’s hearts and minds, maybe even deterring those who have something to hide in their social media.

But Masood seems to have secured his visa and enter the United States prior to this social media requirement, although there’s a chance he may have been required to under earlier pilot programs.

To be fair, probably fewer dangerous terrorists than not end up in intelligence databases, leaving those responsible to somehow read hearts and minds.

A labor-intensive investigation, such as checking a petitioner’s online life, interviewing friends, relatives and former employers might turn up a terrorism problem. But those kinds of investigations, while certainly helped by the social media and email address requirements now, are still rare and not normalized.

“You’d need a crazy Carrie,” the State Department officer said, referring to the lead character in the television series “Homeland,” to uncover a prospective terrorist applying for an H1-B visa with current protocols and resources. “There’s only so much you can do. You do everything you possibly can and, just, you know…? It sounds like this guy was the model citizen. If all of his paperwork was in order, and a consulate officer said ‘he’s a doctor, he’s going to the Mayo Clinic,’ they’re just not going to do a lot of checking.”