Iranian avengers, in the form of Quds Force-supported Hezbollah operatives of the clandestine “Unit 910,” are stationed in cities across America, set to activate pending distant command on target lists they have painstakingly developed over time. Hezbollah operatives also are positioned throughout Latin America. Here’s how we know.

By Todd Bensman as originally published January 7, 2019 in The Federalist

Weirdly absent from much of the professional speculation about where and how Iran will exact its promised “severe revenge” for the U.S. drone strike killing of Quds Force Gen. Qassem Suleimani is mention of the dead man’s highly suggestive hint. During a time of intense saber rattling between Iran and President Donald Trump in July 2018, Suleimani gave a speech during which he called out the American president: “Mr. Gambler, Trump! I’m telling you that we are close to you, exactly where you wouldn’t think that we are.”

So what might Suleimani have meant when he suggested his reach was closer than we think? You’d never know it from New York Times and Washington Post analyses. Their commentaries about where Iran and its Hezbollah proxy might strike primarily quote prognosticators naming bullseyes not only far away from the American homeland – American troops on Middle East bases, allies such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, shipping in the Persian Gulf, or American officials and citizens presumably also overseas – but also exactly where anyone would think the attackers are.

Here’s what is missing from the analysis. Iranian avengers, in the form of Quds Force-supported Hezbollah operatives of the clandestine “Unit 910,” are stationed in cities across America, set to activate pending distant command on target lists they have painstakingly developed over time. Hezbollah operatives also are positioned throughout Latin America, where American officials and economic interests are ubiquitous, at least as close as Nicaragua.

Terrorists Planted In the U.S. to ‘Carry Out Assassinations’

We know Shiite Muslims from Lebanon have been recruited and trained to live in American cities as sleeper agents of Hezbollah’s so-called clandestine External Security Organization (ESO), known colloquially as Unit 910, because agents have been prosecuted over the years, leaving behind detailed public records. The most current source of public information about Unit 910 in America comes from two federal prosecutions that resulted in 2019 convictions, one of Ali Kourani in the Bronx, New York, and the other of Samer El Debek in Dearborn, Michigan.

These Lebanese immigrant terrorist spies were routinely sent home to train in weapons, spycraft, and killing on American soil as soon as they were eligible for useful U.S. citizenship and passports. Their main purpose from about 2007 until their 2017 arrests was to pose in plain sight as normal immigrant family men while they collected weapons and built target lists for when they were activated to strike, court records show.

Their targets tended to be Jewish Americans, Israelis inside the United States, and symbolic and pragmatic sites of importance. For example, after undergoing counter-surveillance and weapons training on trips to Lebanon, Kourani’s handler had him identify Jewish businessmen in New York City who were former or current members of the Israeli Defense Forces worth killing.

Kourani cased a government armory in Manhattan and scoped out the FBI and U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services buildings, sending video to Lebanon. He also sent intelligence on how passengers disembarked from planes at John F. Kennedy International Airport, how U.S. customs agents screened and collected luggage, and the locations of security personnel, cameras, and magnetometers. Kourani located storage spaces where firearms and a legal explosive known as “samad” could be stockpiled. He was told to buy drones, night-vision goggles, and high-powered cameras.

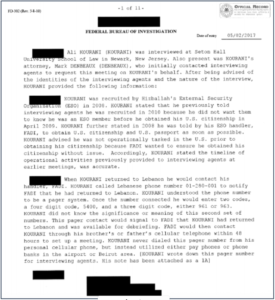

The purpose of all of this, he confessed to FBI agents, was to build a capability for “assassinations and attacks in the U.S.” As one FBI document paraphrased, Kourani lived a double life as one of Hezbollah’s “sleepers — tasked to maintain ostensibly normal lives, who could be tasked with operational activity should the ESO decide to take action.”

In Michigan, El Debek operated on the same model, according to the criminal complaint. He too was a salaried operative dating to about 2007 ($1,000 a month plus medical expenses), trained and indoctrinated during multiple trips back to Lebanon to kill on command inside the United States when ordered. El Debek specialized in building bombs.

The U.S. citizenship and passport came in handy; Hezbollah sent El Debek to Thailand to transfer explosives out of a safe house and at least twice to Panama, where he built target lists of Americans and Israelis in 2011 and 2012.

Posing as an entrepreneur, El Debek surveilled the American and Israeli embassies and the Panama Canal. He noted U.S. embassy security, especially the “periods of heavy traffic into and out of the embassy, vehicular patterns in front of it, and the locations of houses and apartments,” records show. El Debek located hardware stores that sold bomb precursors such as acetone and battery acid. He sent photos and notes to Lebanon, where they no doubt handily remain.

While the extent of Unit 910 cadres in American cities is publicly unknown, the cautious presumption should be that El Debek and Kourani were hardly the only two. Other prosecutions date to 9/11, including a 2011 plot authorized by Suleimani himself for a Texas operative to assassinate the Saudi ambassador in Washington, D.C., at Cafe Milano, a plan which failed miserably.

Indeed, lightly redacted, normally classified internal FBI reports show Kourani named 15 probable operatives in New York, New Jersey, Florida, and Canada. The documents name a Queens mosque Kourani said was aligned with Hezbollah and list the names of sympathizers involved in credit card fraud, counterfeit clothing rackets, an auto parts theft scam, and schemes to export cars to West Africa, a Hezbollah global money-laundering hallmark.

The network is prevalent enough in Western countries that an “association of Western intelligence organizations” hosts a public website titled “Stop 910.” In English, Spanish, and Arabic, the site provides photos of suspected agents and instructions for how to anonymously inform.

Bases Are as Close as Nicaragua

As a journalist during a time of extreme Iran-U.S. tensions in 2007, I traveled to Nicaragua after U.S. nemesis President Daniel Ortega struck close bilateral relations with Iran, which opened a consulate in Managua. I found the Iranian compound in a posh neighborhood, guarded by Nicaraguan troops. For three days, I knocked on the tall metal gates, asking to interview the new ambassador. “Soon, very soon, but not today,” a polite aide always told me.

Frustrated that all I was getting to see was the peak of a limp Iranian national flag jutting over the tall gates, I clambered up to a neighboring building rooftop and shot photos of the compound’s interior, spy-like, then went off to interview Sandinista leaders and regular citizens about the Iranians encamped in their country.

Journalists at the country’s largest-circulation newspaper, La Prensa, provided leaked government documents showing that Nicaragua’s chief immigration minister had authorized 21 Iranian men to enter the country visa-free, leaving no paper trail. I reported that other local media accounts at the time named Quds Force operatives who came in under diplomatic cover and traveled to Honduras and El Salvador. Iran and Nicaragua remain close, with Iran sending its foreign affairs minister in July 2019.

Latin America all around Nicaragua is target-rich in Americans, Israelis, embassies, and Jewish communities involved in regional commerce and diplomacy. As evidenced by El Debek’s 2011-2012 surveillance trips to Panama, these targets are of clear interest to Iran-Hezbollah. The U.S. State Department’s 2017 and 2018 Country Reports on Terrorism found that Iran-Hezbollah “continued its long history of activity” in Latin America, such as illicit smuggling and fundraising activity but also “helping to plan and support acts of terrorism.”

In Argentina, where Iran-Hezbollah agents bombed two Jewish facilities in the early 1990s, the government froze assets of 14 Hezbollah associates, some of whom had “worked closely with numerous extremists” in a free trade zone shared among Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil. In Peru, authorities arrested an apparent Unit 910 operative named Muhammad Ghaleb Hamdar for stockpiling explosives and weapons and using false documents. Operatives were found in Colombia and Venezuela. In 2017, Bolivia uncovered a Hezbollah cache of explosives.

Thanks to Trump’s vow to hit 52 identified Iran-Hezbollah targets if any Americans are killed, some foreign policy analysts predict a less-dramatic revenge attack than worst-case scenarios like this one. But so long as the world is entertaining worst-case scenarios, major U.S. journals do average Americans a disservice in so conspicuously omitting that Iran-Hezbollah has for years prepared to strike in their own hometowns. “Closer than you think,” as Suleimani said.