Convicted terrorist John Walker Lindh was released from prison a week ago. What’s the government doing to make sure former terrorists don’t reoffend? Answer: pretty much nothing. America is at the mercy of released former (or formerly incarcerated, at least) terrorists.

By Todd Bensman as originally published in The Federalist on May 30, 2019

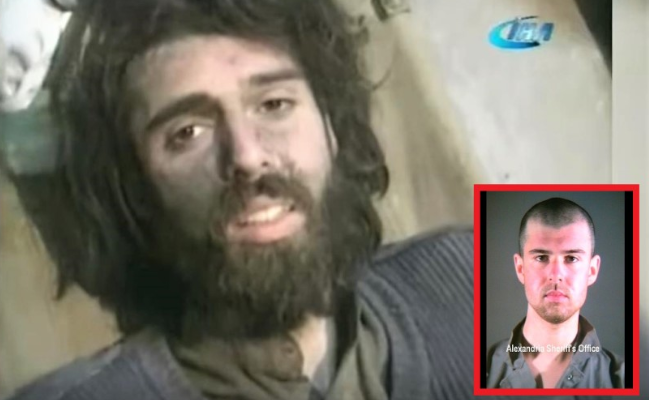

The May 23 release from federal prison of John Walker Lindh, the so-called “American Taliban” captured on a smoking Afghanistan battlefield right after 9/11, put as much chill in the air as the unchaining of serial killers Ted Bundy or Charles Manson would.

His release into American society amid reports that Lindh had, during his 17-year penance behind bars in Indiana, preserved his commitment to violent Islamist jihad and raises an obvious question: What have American homeland security and law enforcement done to ensure Lindh won’t use his newfound freedom to act on his religious commitment to kill infidels?

The unfortunate answer is that America is pretty much at the mercy of released former (or formerly incarcerated, at least) terrorists. I know this from my government experience with this very issue as a homeland security intelligence practitioner in Texas, where a significant number of individuals convicted as a result of terrorism investigations served their prescribed time and were released.

Here are some takeaways from my experience:

- A majority of terrorism convictions after 9/11 landed prison sentences of less than 10 years, so Lindh is far from the first to be released into society—only one of the most publicly prominent.

- Despite years of such releases, neither the U.S. Bureau of Prisons, nor any government agency, systematically tracks or studies terrorism recidivism so that risk can be assessed and programs implemented to reduce it. Therefore, no one really knows how many have recommitted or, among those who have, what the consequences have been.

- Once terrorist convicts are released, neither the FBI nor the Department of Homeland Security have the legal footing to expend resources to surveil or otherwise track them without criminal predicate or probable cause.

- Federal parole officers are currently the only (and best-positioned) law enforcement officers to monitor for the potentially criminal behavior of released terrorist convicts often serving some years on “supervised release,” or court-ordered probation. Violations of probation terms can mean a return to prison for the convict, and even justify a fresh FBI counterterrorism investigation. However, most federal parole officers are overworked and overburdened with non-terrorist convicts and are not equipped to look at their terrorist convicts in any concerted way, even if some do out of conscience.

- Beyond federal parole officers, no other law enforcement agencies are informed that terrorist convicts are being released into their jurisdictions.

Is Recidivism a Problem for Once-Incarcerated Terrorists?

According to one 2017 count by George Washington University, 450 people of an average age of 27 are currently incarcerated for terrorism-related crimes, serving an average of 13 years in prison. (Many people had already served their times and gained release before that count took place, so those numbers might be artificially low.)

It may well be that the recidivism risk is fairly low or moderate, but it’s hard to say. Any effort to count is hobbled by the fact that no government agency has systematically paid attention to terrorist recidivism or apparently thought much about mechanisms to monitor convicts post-release in a way that would provide meaningful intelligence in a lawful manner.

A decade after 9/11, one Naval Postgraduate School researcher attempted an “extensive” effort to assess the threat and to identify locations of released terrorist convicts. In his master’s degree thesis “Freed: Ripples of the Convicted and Released Terrorist in America,” Michael A. Brown came away with “an evidentiary black hole.” He had no choice but to conclude that “we do not know if convicted or released terrorists present a threat,” that there was no defined entity responsible for convicted and released terrorists, and that convicted terrorists are treated no differently than most convicted criminals after they are released.

It should go without saying that past behavior is not always an indicator of future behavior. Knee-jerk assumptions about an unquantified danger are not warranted. Those released who have served their legal obligations to pay for their crimes have a right to reset as productive citizens, unmolested by any unusual law enforcement pressure. Some convicted terrorists will have learned their lessons or unwound their religious zeal for the jihad behind bars.

A good number who are foreign nationals will be deported as soon as they finish their terms, so no problem for the homeland there. Others are providing considerable assistance to counterterror investigations, such as some of the Lackawanna Six. Still others, if they do recommit, might do so with money and material rather than bombs and bloodshed.

On the other hand, we know that some former terrorism prisoners recommit in other parts of the world with plenty of bombs and bloodshed—and in the United States. In 2017, a report by The Washington Institute concluded that the Bureau of Prisons fields no terrorism disengagement programs inside its facilities, meaning local communities have no idea whether they are receiving a die-hard or reformed terrorist.

Do We Have Any Reliable Data?

The most studied and reliable recidivism data involving terrorist detainees involves those released from the U.S. military’s Guantanamo Bay base, often to third-country rehabilitation programs. As of 2012, at the height of President Barack Obama’s effort to empty the facility of terrorists captured abroad, about a third of the 676 former detainees did so or were suspected of “reengaging,” according to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Some convicted terrorists in the United States have recommitted and landed back in prison, even if all that is publicly known about these is purely anecdotal. For instance, Garland, Texas attacker and Islamic State sympathizer Elton Simpson was convicted in 2010 of lying to FBI agents conducting a counterterror investigation into his plans to join the Somali terrorist group al-Shabab. He was given three years’ probation and released, as we are well aware now, to go on to die in the Texas attack.

Georgia resident Abdelghani Meskini, convicted as a co-conspirator in the December 1999 Millennium Bombing plot, was released in 2005. But he was re-incarcerated in 2010 for purchasing an AK-47-style rifle after conducting research on al-Qaida recruiter Anwar al-Awlaki, local U.S. military installations, gun stores, and the November 2009 Fort Hood, Texas, shootings, according to court records from the second case. Thankfully, we won’t ever know how much blood he might have shed.

But we do know in the case of Seattle, Washington, resident Ali Mohammad Brown. He went on a jihad-inspired murder spree that claimed four victims across the country in 2014 and 2015, after a 2005 conviction on bank fraud charges related to a scheme to fund al-Shabab, for which he served time in federal prison. Authorities had lost track of Brown in the years since his release.

So we know recidivism is happening and can happen, especially with convicts less publicly known than Lindh, who will no doubt have eyes on him in some form.

What to Do about Lingering Terrorist Threats

Since the question is raised in so public a fashion with Lindh’s release, America’s homeland security enterprise may be more open to suggestions as to how to reduce risk. Agencies should do these things right away, at least:

- Conduct a comprehensive government study, preferably headed by the Bureau of Prisons and the Department of Justice, quantifying how many recidivists are in custody and how they ended up back behind bars, as well as to account for the number of released inmates who did not re-offend after five years.

- Require the U.S. Probation Officer corps to systematically account for terrorist convicts it supervises and establish requirements for intelligence collection above and beyond the regimen of monitoring ordinary criminals, to meet the much-different needs of FBI Joint Terrorism Task Forces. Probation officers should be given access to additional resources for this effort to include the intelligence analysts of other agencies and classified data systems. One consideration is to draw on the resources of local fusion centers.

- Establish a mechanism to alert local community law enforcement when a terrorist convict is to be released, especially those still showing interest in violence during their last months in prison, and ensure that each remains on the U.S. terrorism watch list.

It’s almost certain that however Lindh is monitored will be ad hoc. The time has long since passed for ad hoc approaches to counterterrorism as more and more Lindhs get released into our communities.Todd Bensman is a Texas-based senior national security fellow for the Center for Immigration Studies and a writing fellow for the Middle East Forum. For nearly a decade, Bensman led counterterrorism-related intelligence efforts for the Texas Intelligence and Counterterrorism Division. Follow him on Twitter @BensmanTodd. Bensman also worked for The Dallas Morning News, CBS, and Hearst Newspapers. He reported extensively on national security and border issues after 9/11 and worked from more than 25 countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.