A mysterious ranch east of San Antonio, home to a Noah’s Ark of exotic animal species, serves as an opulent family haven for the iconoclastic leader of Light of the World Church, a controversial Mexico-based denomination followed by allegations of child sexual abuse and intimidation. Leader Samuel Juaquin Flores claims he and his family are deities with a direct link to Jesus.

By TODD BENSMAN as Originally published in 2009 by The San Antonio Express-News

KINGSBURY, Texas — Almost every day, at least a few of the 27,500 motorists who drive Interstate 10 through this speck of a ranching community pull over to check out a curious fenced ranch just off the highway.

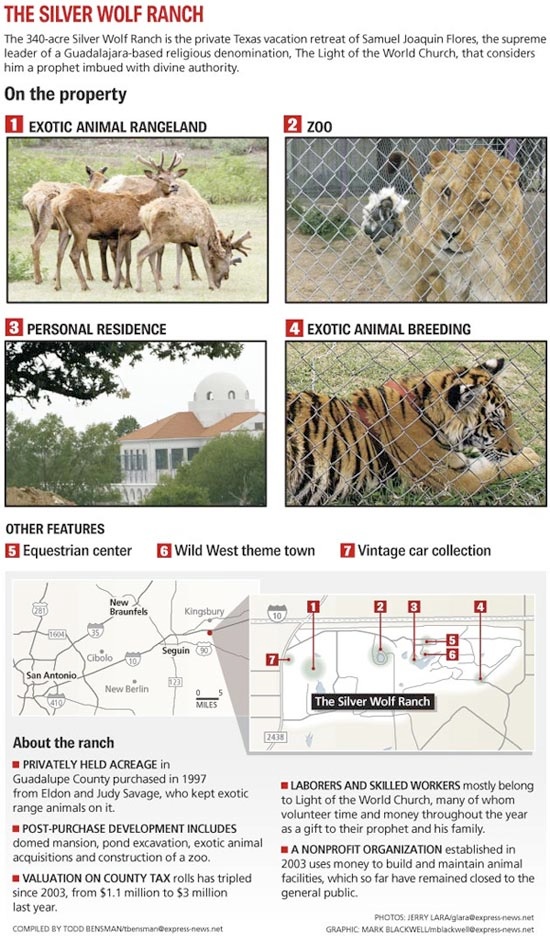

Easily visible from the interstate, twin white domes of a massive structure poke up like mushrooms on the 340-acre forested reserve. A giant bronze bison statue stands in plain view, as do live stick-legged emu birds and ostriches.

But tourists never get through the well-appointed limestone facade entrance that seems to beckon them into The Silver Wolf Ranch. As they have for 10 years since the property came under new ownership, polite Spanish-speaking workers shoo away the camera-toting motorists with the same unrequited promise; the ranch will open soon, very soon. It never does, though.

The land, a 40-minute drive from San Antonio, remains just as enigmatic to immediate neighbors left to ruminate — sometimes darkly — about relentless construction activity, howls of unseen wolves, reports of gun-carrying guards, and especially the tint-windowed SUV caravans for which the gates do occasionally open.

“I don’t know nothing; I don’t want to get involved,” said neighbor Jesse Weinaug, who owns a cattle ranch next door. “They don’t come over here. I don’t go over there. It ain’t none of my business.”

But now the curtain can be thrown back from The Silver Wolf Ranch. The San Antonio Express-News was given limited access to parts of the property and to those who speak for its long-hermetic owners.

The property, it turns out, is the private playground of a Mexican family that has grown immensely wealthy and politically powerful while ruling as a dynasty over the controversial religious denomination known as Iglesia La Luz del Mundo, or The Light of the World Church. The Pentecostal-like denomination’s supreme leader, the iconoclastic 71-year-old Apostle Samuel Joaquin Flores, is viewed as a messianic figure to be worshipped as a direct link to God and obeyed by church faithful in Mexico and abroad.

Some of Joaquin’s nine grown children, themselves considered quasi-divine royalty, have transformed their Texas land into a lavish private zoo-themed family retreat for their father’s enjoyment on the scale of some owned by American pop stars or Saudi oil sheiks. The Guadalajara-headquartered denomination, which claims five million members worldwide, a figure disputed by some religion researchers, is not without some tenacious allegations of wrongdoing against Joaquin involving abusive treatment of followers. Denomination officials strongly deny all such allegations as part of a sophisticated smear campaign by a jealous Catholic Church in Mexico.

None of this controversy has followed Joaquin north to his Kingsbury haven in any public way, perhaps because he is often hidden behind those tinted SUV windows described by neighbors. The Joaquins declined to be interviewed.

But lifelong church member Maria Elena Castillo, a Seguin lawyer who handles ranch legal affairs while doubling as zookeeper, explained why Joaquin has never felt the need to break bread with neighbors all these years. “It’s a private property,” she said. “If he’s high profile, he’s showing off; if he’s low profile, he’s hiding something. You can’t win either way. Everybody who needs to know about us, knows about us.”

The ranch is essentially divided into two parts. One will always remain the exclusive domain of the family. The other part of the property, Castillo said, operates as a federally registered nonprofit zoo and wildlife rescue refuge destined to be open to the public. Its caged habitats are arranged out of view from the interstate in a semi-circle around an excavated pond out of which towers a cartoonish giraffe statue.

Federal tax records show the nonprofit has accumulated upwards of $1 million since 2004. Much of this money comes from church collections taken weekly and annually from the faithful in Texas, Castillo said.

IRS regulations require nonprofits to actively promote their tax-exempt purpose of benefiting the public and not the personal wealth of anyone, said Bruce Hopkins, a lawyer who teaches tax-exempt organizations about tax law.

“The government would expect some public access to the property. Saying it and having all those years go by is a bit troubling,” he said.

Church officials are careful to point out the donations from the faithful go into the nonprofit and does not benefit the family’s private holdings. Castillo said the zoo and its complement of full-grown lions, a white tiger with cancer and an aviary full of squawking exotic birds, benefits the public in part by taking doomed or homeless animals off the hands of surrounding counties, like two tigers to be euthanized for mauling their original owners’ son.

As a rambunctious silver wolf named Roco bounded like a giant domesticated puppy around his cage, Castillo explained how the family also lets some veterinary and children’s groups take educational field trips inside the nonprofit zoo. An area veterinary clinic that she said takes employees on field trips there did not return repeated phone calls.

“Even though it’s private, they opened it up to community,” Castillo said. “I think that’s very honorable.”

Reiterating a well-worn promise, she said the zoo will be opened to the general public soon – “probably next summer.”

“Progress is slow,” she explained, “because it’s being funded at private expense,” and improving it sufficiently for public enjoyment is a huge job.

The denomination’s North America spokesmen, California-based Pastor Carlos Montemayor, reiterated during a recent interview in Austin that the ranch plays no role whatsoever in La Luz del Mundo affairs or vise versa.

The Spanish-speaking workers often seen by neighbors and curious motorists are church volunteers who contribute labor to build and maintain the ranch, especially on weekends.

“It’s personal,” Montemayor said of the property, paid for out of family earnings from businesses such as a travel agency in Guadalajara. “No one can benefit from church assets, either in Mexico or the U.S. Everything in our church goes to the people.”

A ‘blood lineage’

Joaquin’s military officer father, Eusebio Joaquin Gonzalez, founded Iglesia La Luz del Mundo in 1926 as a breakaway from the Catholic Church. Taking the title Apostle Aaron, he proclaimed himself a kind of latter-day Moses directly empowered by God to restore true Christianity to a chosen people.

The model, which offered many social services, quickly caught on with Mexico’s poor in Guadalajara. And in the decades since Samuel Joaquin succeeded his deceased father in 1964, ostensibly by divine selection, the group has expanded into countries around the world, especially in Latin America.

It proselytizes a one-of-a-kind unwritten theology. According to published academic research in Mexico, church doctrines emphasize a status as the world’s only real Christian church, and followers are encouraged to revere Joaquin as divinely appointed “king” or “apostle” with the only direct line to Jesus. Several thousand “unconditionals” are said to pledge irrevocable vows of lifelong, unquestioning obedience to Joaquin.

U.S. and Mexican scholars who have studied the denomination say marriages for unconditionals are arranged, their lives closely planned and their loyalty monitored. There are prescribed dress codes enforcing modesty for women, relentless tithing requests and mandatory annual pilgrimages to celebrate Christ’s Last Supper at the “mother church” in Guadalajara, on Apostle Aaron’s Aug. 14 birthday. Another major religious event is Samuel Joaquin’s Feb. 14 birthday, when, according to church teaching, he was born dead but resurrected by his father.

Articles published in the Mexico City-based Journal for the Academic Study of Religions have described a patriarchal, autocratic leadership that has amassed significant political power in Mexico by leveraging the votes of its members, and deploys the “unconditionals” to surveil and control a broader membership. The church, according to these scholarly articles, has accrued fabulous wealth from tithings, real estate development around certain churches, and a U.S. expansion strategy tapping a more affluent recruit base in border states like Texas and California.

The Joaquin children are revered as princes and princesses who are said to share in it all, although a spokesman denied they enjoy any authority beyond that conferred by their roles as rank and file ministers.

“This is a formidable religious institution within the Mexican context,” said Dr. Bobby Alexander, associate professor of sociology at the University of Texas–Dallas, who has studied the denomination. “The offspring of Samuel are revered, as descendants of semi-divine lineage. It’s a blood lineage.”

One son who has served as pastor of the denomination’s lavish Houston church, the Texas-based Benjamin Joaquin, who built the Kingsbury property, is thought to be in line for succession as God’s next prophet.

A troubled past

Allegations of child abuse and the violent intimidation of dissidents stung the church hierarchy at the very time the Joaquins acquired the ranch from Eldon and Judy Savage 10 years ago. In fact, the family was weathering an international media storm fed by dissidents in Mexico and the first academic studies revealing the secretive denomination’s practices.

Some dissidents went public, in academic journals such as the Journal of the Study of Religions, and in Mexico’s largest media outlets, with allegations that Samuel Joaquin many years earlier had sexually abused them as children in violent rituals at his various mansions, sometimes with blessings from fanatically loyal parents.

Dr. Jorge Erdely, co-editor of the magazine, wrote in a July 2004 article published in the Proceedings of the IV International Congress of Socio-Religious Studies, that Joaquin justified the abuses as part of a ceremonial King “Solomonic” right to a harem made up of anyone he chooses. Erdely declined to comment to the Express-News.

Light of the World church founder Eusebio Joaquin Gonzalez (second from left), later known as “Apostle Aaron,” started the Pentecostal sect in 1926. In this undated family photo, he has his arm around current leader Samuel Joaquin Flores, who succeeded his father in 1964.

Erderly and other scholars have written that Joaquin has wielded an armed wing of unconditionals to violently quell outspoken dissidents and enforce allegiance.

Some of the allegations followed the church north over the U.S. border in the late 1990s, to Ontario, Calif., when a public controversy broke out as local residents tried to halt construction of a La Luz del Mundo church, claiming it was a dangerous cult.

But church officials strongly denied then and now that any abuse of members took place and that there is no armed militia. Luz del Mundo representatives provided the Express-News the first and last page of what appeared to be a 22-page document from Mexico’s Interior Ministry that they said proves the allegations never had any merit.

The last page concluded that the charges were “manifestly inadmissible.” In telephone interviews, government officials told the Express-News several state of Jalisco criminal complaints against Joaquin, old when they were lodged, went nowhere in part because of statutes of limitations.

“That was one of the problems the investigation had,” said Lino Gonzalez, spokesman for the state prosecutor’s office in Guadalajara. “And on the other hand, I believe (the accusations) were unfounded.”

Montemayor attributes such allegations to a Roman Catholic Church conspiracy to halt steady losses of faithful to La Luz del Mundo.

“There’s an organization that feels a lot of jealousy toward our church’s growth and fame,” he said. “And that’s not very Christian.”

Father Antonio Gutierrez Montano, spokesman for the Archdiocese of Guadalajara, denied the church worked to discredit “the religious group called Luz del Mundo.”

“We don’t care about ruining anyone’s reputation,” he said. “It’s tiring and does not lead anywhere.”

The denomination has since enjoyed expansion throughout the U.S., including Texas and other states with large Hispanic immigrant communities. In 2005, the denomination prevailed in a California civil court challenging the Ontario defeat, and the church is finally going up there.

Among its many other projects is a palatial $18 million white marbled Houston church and the acquisition of small churches throughout the state, including two San Antonio chapels. So, said Montemayor, a family vacation property between Houston and San Antonio made sense given the Texas growth strategy.

Unlike in the Catholic Church, Montemayor pointed out, La Luz del Mundo pastors take no vow of poverty in their private lives.

In that, the denomination leadership practices what it preaches.

A Wild West theme town

Erdely, the co-editor of the Academic Journal for the Study of Religions in Mexico City, wrote in his July 2004 article that the family’s many luxurious mansions and churches are designed to project “important symbolic value for the faithful” because they embody the “sacred offices of high priest messianic kingship.”

Whether that was the intent, the family has succeeded in building a major residential edifice on its property outside of Seguin. County tax assessment records show the land parcel upon which the house stands is valued at $1.7 million, nearly triple what it was five years ago. The house remains under construction even seven years after work began in earnest.

The total assessed value of all their acreage, driven by building and other improvements, tripled from $1.1 million in 2003 to $3 million now.

The home anchors a Disneyland-like wonderland of animals. It sits on the shores of a several-acre lake excavated to create a waterfront view. An island sports a manicured lawn and gazebo connected to opposing shorelines by hanging suspension footbridges. A Wild West theme town shares the shoreline, complete with a faux jail and saloon and a modern playscape where family birthday parties are held.

Behind some of the facades are condo-style living quarters for guests, said Vaspi Coronado, who manages the ranch. No photographs of any of this were allowed.

Not far are stables for the family’s Clydesdales and other horses, which can be ridden around a quarter-mile track on site and outfitted from a well-stocked tack room.

On another part of the land stands a long rectangular warehouse, its sides painted with the likenesses of classic automobiles on a bright blue background. Coronado said each painting represents a real restored vintage automobile kept inside, the family’s private collection. A crew of Spanish-speaking mechanics keeps them shined and tuned. But a request to view the vehicles was declined.

Church leader Samuel Joaquin Flores greets worshippers at La Hermosa Provincia as parishioners try to touch him during the church’s ‘Holy Convocation’ week in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2003. The church was founded in the city.

Omnipresent throughout the landscape, in addition to church faithful providing caretaking labor, are wandering zebras, red deer and ostriches. Some animals were vestiges from the previous owners, who kept the place stocked with exotics. But most of the rarities, like the Mongolian yak and European red deer, have been painstakingly added since the family moved in. A baby brown bear named Boo trundled around at the end of a leash one recent day, delighting the children of some of the volunteer workers.

Coronado said the public will be able to see some of this on a drive-through safari, when the ranch opens – “soon.”

But until the ranch actually lets the public in, it seems likely to keep the local fires of suspicion and gossip stoked, with no specific cause, just as when the family first bought the land.

At the time, Guadalupe County Sheriff Melvin Harborth called in the Texas Department of Public Safety’s criminal intelligence unit after receiving reports of gun-toting guards at the old Savage Ranch.

“We checked out everything we could on the people who own that property,” he said. “We didn’t find anything that was illegal. …Everybody’s got freedom of religion.”

Ten years later, Sheriff Arnold Zwicke said, “We continue to watch it. But they haven’t given us anything reason to do anything. They’re good citizens.”