Suggests coordination breakdown between U.S. homeland security and Mexican intelligence amid overwhelming mass-migration crisis

By Todd Bensman as originally published December 28, 2021 by the Center for Immigration Studies

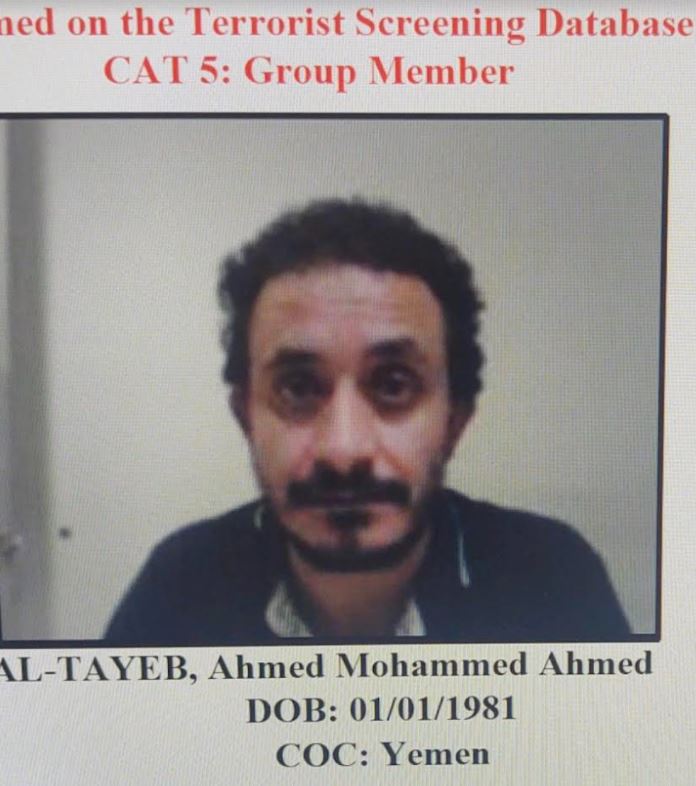

AUSTIN, Texas – On November 20, the government of Mexico released a Yemeni migrant who was on the FBI’s terrorist watch list – on condition that he “report weekly” to Mexican immigration authorities, according to a law enforcement intelligence document obtained by the Center for Immigration Studies. Instead, of course, Ahmed Mohammed Ahmed Al-Tayab disappeared.

By the first week of December, the Del Rio Sector Border Intelligence Group was distributing a “Be on the Lookout” bulletin warning (known in law enforcement as a BOLO) that the Mexico-released “Special Interest Migrant” is suspected of planning to travel to the U.S. southern border illegally.” CIS has obtained this BOLO.

It said Al-Tayeb is listed on the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Database and by US Customs and Border Protection’s intelligence office as a “Category 5 group member” He is the latest in a string of such discoveries during 2021 amid an historic mass-migration crisis that has overwhelmed the U.S. border security apparatus, to include a number of other terrorism-connected Yemenis and, most recently, a Saudi terrorism suspect on the FBI list caught near Yuma, Arizona.

Crisis-related breakdown of Mexico-U.S. homeland security protocols?

What distinguishes this episode from most others, however, is that other information in the BOLO document suggests the mass-migration crisis led to a dangerous and unusual breakdown in coordination between Mexico and American homeland security, which left an FBI watch-listed migrant on the loose headed for the southern border in the Del Rio and Eagle Pass area of Texas. Mexico is almost always alerts the FBI and American law enforcement agencies stationed in the country of “special interest aliens” from countries such as Yemen, for checks against terrorist watch lists.

The BOLO states that Mexico first encountered the Yemeni in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, in April 2021, just across the Rio Grande from Eagle Pass, Texas. The Mexicans deported Al-Tayeb, to where it does not say. But by July 2021, he was back in northern Mexico. Mexican immigration apprehended and detained him.

The Mexicans kept Al-Tayeb in their custody for about four months, until November 20, and then did something inexplicable: “subject was released by Mexican immigration and ordered to report weekly,” the BOLO stated. It’s unclear if Al-Tayeb remains free and on the move.

What is more clear is that Mexico released Al-Tayeb on the self-reporting honor system without informing American homeland security agencies that normally work closely with Mexico on all suspected migrant jihadists. These agencies would never have consented to such a release had they been informed of it per years of normal protocol, and felt duty-bound to issue a BOLO to agencies all along the border for the Yemeni’s capture.

As disclosed at great length in Chapter 5 of my book, America’s Covert Border War, the Untold Story of the Nation’s Battle to Prevent Jihadist Infiltration, the United States and Mexico have closely coordinated on the handling of jihadist migrants since shortly after 9/11, in several established ways.

For starters, Mexico informs in-country FBI and ICE Homeland Security Investigations officers every time it catches one. American officers stationed in Mexico are then let into Mexican detention facilities to interrogate the migrants and assess their danger and terrorism connectivity.

The Americans then influence one of two main outcomes: either Mexico deports such terrorist suspects, as it did Al-Tayeb the first time he was caught in April, or else Mexican intelligence officers will walk suspects to the halfway point of an international bridge and hand them off to American law enforcement for more elaborate investigation (and usually deportations from the United States). For instance, between 2014 and 2019, Mexico deported 19 suspected migrant terrorists.

Obviously, given the BOLO’s distribution earlier this month, an outcome wherein a Category 5 FBI-watchlisted terrorist group member gets released and asked to voluntarily report regularly to Mexican immigration is not on this short list of resolutions.

The times could not possibly be worse for managing this kind of immigration-related national security threat, given that record-setting numbers of migrants from around the world began coursing through Mexico in late 2020 and have overwhelmed both Mexican and U.S. immigration authorities.

A reasonable assumption is that the agencies on both sides of the border that conduct the “Covert Border War” against migrating jihadists camouflaged among other migrants are similarly strained.

Heightened danger during a homeland security-strained border crisis

The still-unfolding story of Al-Tayab is only the latest instance in which the public became aware that suspected terrorists from nations of terrorism concern – “special interest migrants,” as the government BOLO put it – traveled to the southern border among the hundreds of thousands of Latin American and other illegal immigrants.

Americans should know that such suspects are certainly in the mix, a worrying part of the border security crisis, because some have still been caught, fortunately, and brought to public attention this year. A screenshot of the deleted tweet.

A screenshot of the deleted tweet.

Most recently, for instance, Yuma Sector Chief Border Patrol Agent Chris Clem announced the apprehension on Twitter (since deleted) that a “potential terrorist” from Saudi Arabia.

That suspect, the chief said, had apparent connections to “several Yemeni subjects of interest.”

Was Al-Tayeb one of them? We may never know. But other Yemeni migrant terrorist suspects have crossed the southern border in 2021. A horrific civil war in Yemen features a Saudi-backed government on one side and, on other sides, armed Sunni terrorist groups of ISIS and al-Qaeda as well as the rabidly anti-American Shia jihadist militia drawn from radicalized members of the Houthi tribe.

Many individual fighters are probably known to American intelligence agencies, which have worked closely with Saudi intelligence agencies; that’s how they ended up on FBI terrorism watch lists.

As I reported during the summer of 2021, U.S. Customs and Border Protection public affairs put out – and, like Chief Clem’s Tweet about the Saudi, quickly retracted though archived here – a press release announcing two separate border crossings by Yemenis who were already on the FBI terrorism watch list. One apprehension happened in January, just as the migrant crisis was starting, in Calexico, Calif. The second occurred in March, also near Calexico. The latter was on the more rarified No Fly List and was found to be hiding a cell phone sim card in the sole of a shoe, that deleted press release stated.

Those are not the only ones in 2021 either, or before. Clearly, something is happening among Yemenis involved in that civil war. During a border visit in April, U.S. House Minority Leader Rep. Kevin McCarthy reported that Border Patrol agents told him watch-listed migrants from Yemen (as well as Turkey and Iran) were crossing illegally from Mexico among Central Americans.

During relatively slower times at the southern border, in 2019, I reported extensively on a federal prosecution of a Jordanian smuggler who illegally transported at least seven Yemenis over the southern border, also at Piedras Negras, Mexico across from Eagle Pass, Texas.

As San Antonio Express reporter Guillermo Contreras reported, “several” of the Yemenis were connected to terrorist activity.

Has Mexico freed suspected jihadist infiltrators before Al Tayeb, maybe because Mexico’s immigration system also is overwhelmed? Will Mexico keep doing this with suspected terrorists because that’s the easiest way to clear detention centers?

Whatever happened on the Mexican side, this matter cries out for congressional inquiry or investigation by appropriate Offices of Inspector General on the American side, because this should not happen even one more time.