By Todd Bensman as originally published January 17, 2022 by the Center for Immigration Studies

TAPACHULA, Mexico — Between August and December 2021, Mexico mired between 30,000 and 50,000 U.S.-bound immigrants behind a bureaucratic dam in this southernmost city near the Guatemala border, requiring permission slips for onward movement that purposefully took months to get. This slow-roll-them strategy, backed by two-week Mexican detentions and deportations for those caught without papers, was done in line with Biden White House pressure on Mexico City to reduce the political damage of a historic illegal mass migration tsunami ahead of this year’s mid-term elections.

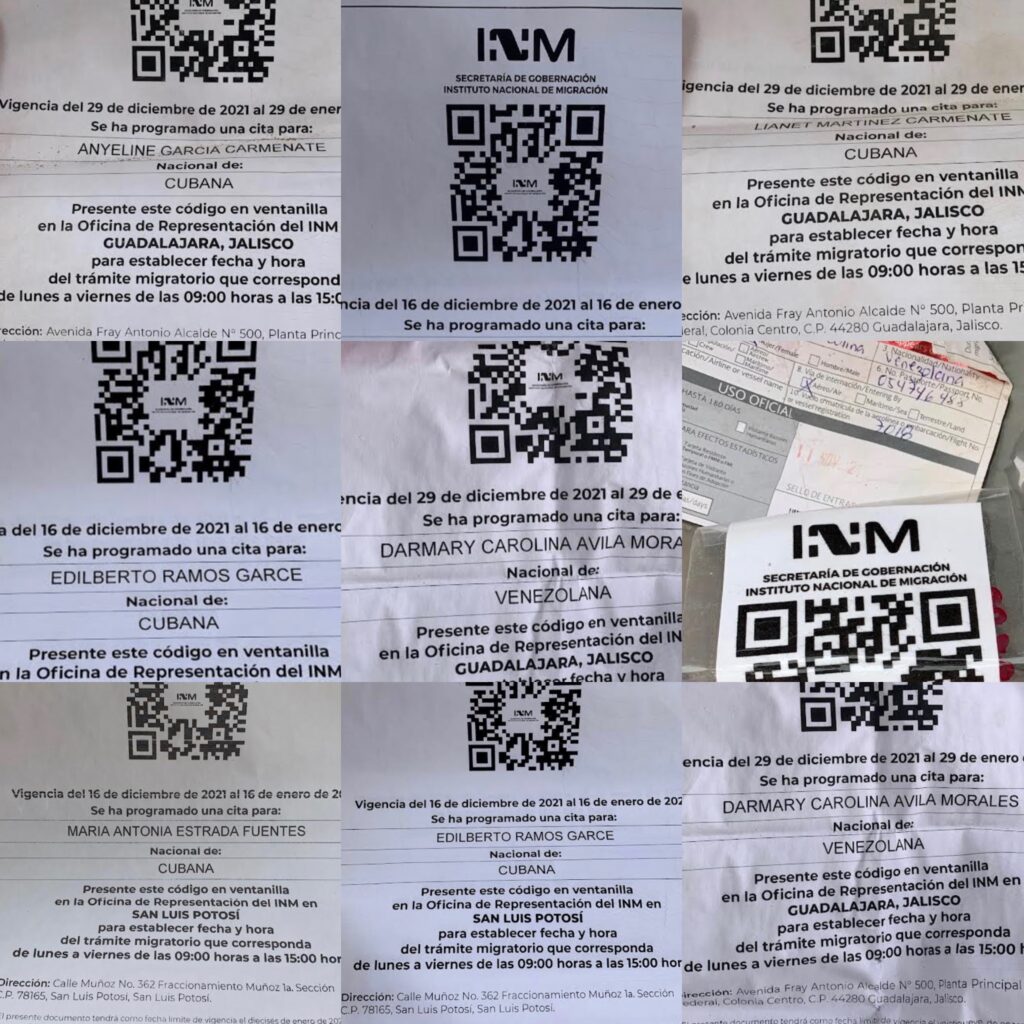

But just after Christmas 2021, following almost nonstop civil disturbances by the dammed-up and frustrated immigrants, the Mexican government suddenly solved everyone’s problem with a crafty ruse to send hundreds of thousands of migrants to the American border in the coming year without raising any alarms. According to Mexican immigration officials, journalists, and immigrant beneficiaries, the Mexican government mass-distributed an electronic “QR code visa” to thousands almost overnight, then arranged for their exodus by hundreds of buses in atomized groupings sent across 14 different Mexican states farther north. Most Americans and even Mexicans failed to notice that a huge but purposefully diffused surge of people to the American border had even happened, let alone why.

In Mexico, big clandestine movements like this in recent years have earned the colloquial term “ant operation”, which connotes an informal tactic by which immigrant smugglers move large volumes of people in small distributed parties and individuals in many single-file lines so that most evade the notice of authorities.

But now, the government of Mexico itself appears to have adopted the ant operation model to clear out the 50,000 immigrants it so openly and proudly backed up behind the Tapachula dam as a favor to the Biden administration. It sent the majority streaming toward the American border almost all at once, only diffused in fleets of buses the government arranged — ant lines all but unseen.

“The whole city [of Tapachula] was collapsing because there were so many here in town and they were blocking the roads and causing disruptions … so that’s why they were moved out,” said Clemente Miguel, director of the local newspaper Noticias de Chiapas. “There’s no infrastructure to hold them all in one area, and no other Mexican state wants them, so they’re intentionally spreading them all out.”

To get this ant operation done quickly, the Mexican government employed a cunning innovation called the “QR code visa.”

The QR code visa is part of an honor-system scheme that asks recipients to voluntarily report to a Mexican immigration office in a particular city by a specified date, ostensibly to apply for and await a more permanent Mexican residency card, copies of the visas show. With this tactic, the government ensured that no huge caravan or Del Rio migrant camp could form that would draw media attention and cause political damage to either the Mexican or American government, or open diplomatic rifts. (A first early Mexican government ant operation in September went awry for lack of sufficient diffusion and caused the Del Rio migrant camp.)

But the American people are already paying the price for insuring governments against political damage.

The Price of Subterfuge

Why would Mexico bother with all the pretense of blocking immigrants in Tapachula until they hit critical mass and the nation is forced to let them all rush forward after a few months?

“It’s double-sided politics,” Miguel, the newspaper publisher, explained. “The immigrants are being told they’re welcome and they’ll be helped. And then [President Andres Manuel Lopez] Obrador is turning around and telling Biden, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll hold them in Mexico.’ That’s the agreement they have. It’s Obrador’s mindset that he wants to be in good standing with migrants and with Biden at the same time.”

But signs abound that a powerful wave of the December QR code visa recipients was already smashing U.S. southern border defenses by mid-January, and tens of thousands are still swamping Border Patrol from Brownsville, Texas, to Yuma, Ariz. Those areas are about a two- or three-day bus ride from Tapachula.

The popular Mexican podcaster and journalist Carmen Aristegui wrote on December 31 that the Mexican government accelerated the transfers of “tens of thousands” of migrants seeking to reach the United States “to various other Mexican regions” and quoted some of them admitting they’d use their new freedom to break for the American border right away. One Cuban woman, for instance, “confessed” that she would use her QR code visa to continue to the United States.

The most credible clue about how this all will go is that QR code visas are showing up crumpled and discarded at Texas and Mexican crossing points along the Rio Grande riverbanks, the newest addition to borderland debris fields.

What can knowing about this do for Americans?

The Boom and Bust Cycle in Tapachula Foretells 2022

The significance of more public understanding about Mexico’s ant operation is that its efforts to put up a big enforcement and blockade show on its own southern border is more than merely phony and ineffective. This presages huge waves of immigrants to the American border every three months, about the time it takes for tens of thousands of newly arriving migrants to show up. Look for QR code visas all over the Rio Grande riverbanks going forward.

During a post-ant-operation field trip to Tapachula, the Center for Immigration Studies found a less crowded, much-relieved city. But the federal tools of immigration enforcement had returned to the very same pretenses of blocking forward immigrant movement at Tapachula.

The government had halted QR code visa issuances by New Years and returned to requiring the old kind of visas that never seemed to arrive. Mexican immigration agents backed by national guard troops were forcing immigrants to wait beyond their budgets and ability to earn money for sustenance, fueling the same sorts of complaints heard in the weeks before December’s ant operation.

CIS observed teams of unarmed officers, with soldiers for muscle, patrol the city’s center, sweating migrants from Senegal, Angola, and Haiti who, if they couldn’t show the papers, might well end up in a detention center for a couple of weeks, a pretty effective prompt to get the paperwork done.

A group of some 15 Senegalese immigrants in the city’s center had missed the happier QR code days by two weeks and were already voicing the familiar refrains that led to the ant operations of September and December.

“It’s difficult because on the road here we spent all of our money,” one Senegalese managed to say in a mixture of French and Spanish. “I can’t stay here in Mexico because I’m out of money. I used it all up. Please help us to enter into America, all of us Senegalese, my friend.”

CIS saw the officers and national guard soldiers putting on the same show at the well-trammeled Suchiate River water crossings where huge numbers often enter from Guatemala aboard rafts made of inflated truck inner tubes.

Several of the immigration officers said their orders were to direct the new arrivals to government offices where they had to register for the chance to apply for Mexican asylum. Those caught without papers might face expulsion to Guatemala or even beyond.

“Our role more than anything is to make sure that the migration is not illegal but made legal,” one said. “In a way, we just guide them to get their paperwork.”

While government immigration officials declined interviews, the cycle was clearly ginning up a new immigrant population boom that by March or April, if past patterns hold, will send forth to the American border another diffused wave of thousands carrying their QR Code visas, many of which will end up as trash on the banks of the Rio Grande.

Luis Garcia Villagran, coordinator at the Center for Human Dignity, a local migrant advocate who organizes caravans out of Tapachula, recently told the local Diario del Sur newspaper that at least 20,000 more are on the way through the Darien gap jungle passage. The passage delivers immigrants from Colombia in South America to Central America’s Panama.

“You only see a few working or selling, exchanging money, or just hanging out, but I consider that in two or three months, for sure,” Villagran said. “we will see the migration continue to the southern border.”

And probably three months after that, and so on during 2022.