See Part II New Records Unveil Surprising Scope of Secretive ‘CBP One’ Entry Scheme, Part III Thousands of ‘Special Interest Aliens’ Posing Potential National Security Risks Entering via CBP One App and Senator Demands Biden Administration Answer Bensman Reports on ‘Abject Failure To Protect U.S. National Security Interests’

By Todd Bensman as published September 21, 2023 by the Center for Immigration Studies

Summary: A little-known part of the Biden administration’s CBP One parole program permits inadmissible aliens to make an appointment to fly directly to airports in the interior of the United States, bypassing the border altogether. Partial data on the program, just obtained by the Center for immigration Studies pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request, reveals that more than 200,000 people from four countries have used this direct-flight and parole program over the past year.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — In January, President Joe Biden’s Department of Homeland Security began implementing the cornerstone of its current Southwest Border management strategy: a series of new “lawful pathways” measures designed to decrease the historically high monthly “encounter” statistics of illegally crossing immigrants and to thin their mass congregations before they become a political problem.

For one of the more publicized measures, DHS cajoles tens of thousands of intending illegal border-crossers per month to instead go on the CBP One smartphone application, and make an appointment with U.S. officials at land ports of entry instead of crossing illegally. After making an appointment, DHS invites these inadmissible aliens to walk over to the American side at the land ports, where U.S. Customs officials quickly “parole” them in, allowing them to travel to a city of their choice in the nation’s interior.

But one of the least noticed, mysterious, and potentially the most controversial of the new rechanneling programs that use the CBP One app allows migrants to take commercial passenger flights from foreign countries straight to their American cities of choice, flying right over the border — and even over Mexico. For this measure, Cubans, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Colombians — while they are still in countries south of Mexico — request “advance travel authorizations” through the same CBP One mobile app and take commercial flights (“at their own expense”) directly into U.S. airports, where U.S. Customs officers parole them into the nation, sight unseen, and in numbers publicly unknown.

Biden officials have rarely, if ever, spoken of this “family unification” flight program in the year since implementing it, perhaps mindful of the political outcry over the late-night “ghost flights” that DHS stealthily arranges to ferry migrant children into various airports, and mindful, too, of strong recent political backlash in large U.S. cities like New York and Chicago to paroled migrants busing themselves in from the border. Here, migrants flying directly into America go uncounted in the monthly Border Patrol tallies, unnoticed, and without media inquiry, virtually all information about it almost hermetically sealed.

But records obtained by the Center for Immigration Studies as part of ongoing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) litigation against U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) show these migrant flights have brought significant numbers of migrants into U.S. cities over most of the past year. (See the Excel files for “Parole Arrivals” for Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.)

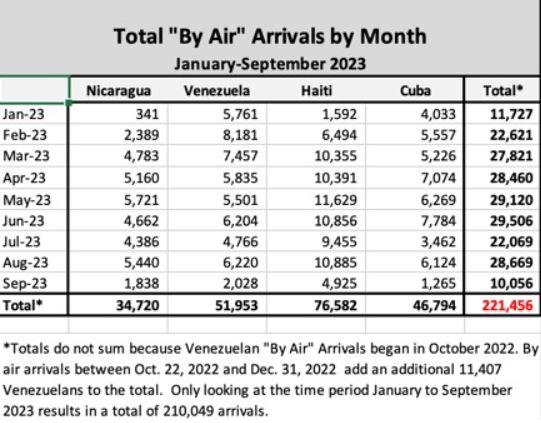

The records show that between late October 2022 and mid-September 2023, the administration approved a total of 221,456 Venezuelans, Haitians, Cubans, and Nicaraguans for “travel mode: air” into still-unspecified interior U.S. ports.

Government policy requires that migrants “approved for travel” must pay for their own tickets: “If approved, the beneficiary is responsible for securing their own travel via commercial air to an interior POE [port of entry],” according to language typical in the relevant Federal Register notices.

The Biden administration did not release the numbers or receiving airports for Colombians or Ukrainians approved to use the direct-flight parole program, which portends much higher total numbers approved to fly in. More recently, the administration added Hondurans, El Salvadorans, and Guatemalans to the direct-flight family reunification program, and their numbers also remain unknown.

The four nationalities for which data was released, however, probably account for the lion’s share of the total who flew in over the past year and provide a rare initial window into how big the program has become.

The data that has been released for the four nationalities shows that these hundreds of thousands of migrants used anywhere from 35 to 43 interior ports of entry, meaning airports staffed by U.S. Customs officers who do the work of paroling them into the United States.

But to date, CBP has redacted and withheld the locations of the 43 interior ports of entry that have been utilized by this direct-flight and parole program, claiming its release would harm law enforcement techniques or procedures.

The administration has proven reluctant to provide any meaningful data about its vaunted CBP One-based border strategy, which it advertises as its central solution to mitigate the unsightly migrant surges as the southern border by using the online interface to manage mass paroles of inadmissible aliens who would otherwise cross illegally.

Since announcing and implementing this direct-flight parole program in October 2022 for Venezuelans and in January for Cubans, Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Colombians, the administration has staved off at least one congressional inquiry (spearheaded by Rep. Tom Tiffany of Wisconsin) for the numbers. Similarly, the Center for Immigration Studies, which filed a FOIA request for the relevant data in March of 2023, was forced to sue CBP in order to obtain the records in a timely manner.

The administration has also sought to limit the release of data on the better-known parole release program using the CBP One appointment app at the physical land ports with Mexico (the one the administration mainly credits with briefly reducing illegal crossings at the border), and still has not provided total numbers over the span of its existence, starting in mid-2021.

The Nameless Airports

In response to CIS’ FOIA request regarding the direct-flight and parole program, CBP has redacted and withheld the locations of the interior U.S. ports of entry into which the migrant applicants are flying after entering their biometric data and other information to DHS through the CBP One system. City leaders and residents would undoubtedly want to know how many are flying into their cities for planning, funding, and public input purposes, at the least.

In correspondence with CIS, CBP attorneys justified their redactions under FOIA Exception 7(E), that generally protects law enforcement “techniques and procedures … in the context of a law enforcement investigation or prosecution” when its public disclosure would cause a “foreseeable harm”.

CBP has not yet fully articulated the reasoning behind its use of Exemption 7(E), as required by law, writing only in a government letter that “CBP has considered the foreseeable harm standard when reviewing the record set above and have applied the FOIA exemptions as required by the statute and the Attorney General’s guidance.”

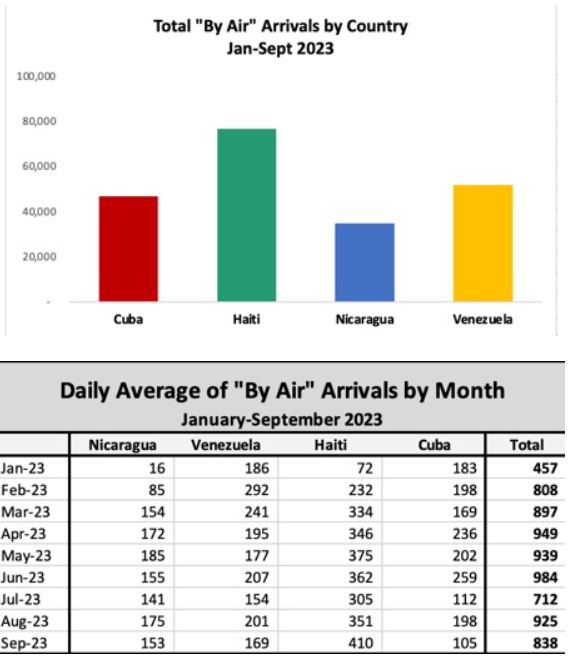

Meanwhile, the limited data that was released about the direct-flights and parole program shows that, of the four nationalities, Haitians flew into U.S. airports in the greatest numbers from January through mid-September, a total of 76,582. These Haitians favored one redacted airport over all 36 into which they have flown. Some 47,768 flew into that airport. Another top receiving airport took in 13,155, and still another 12,833.

The program was offered to Venezuelans a few months earlier, in October 2022. Since then, 63,360 flew into 43 airports, some 39,474 of them into one preferred airport.

Some 46,794 Cubans flew into 41 airports, the majority of them, 33,355, favoring one in particular.

(It’s likely that the preferred airport in all these cases was Miami, but we won’t know for sure unless CBP provides the unredacted information.)

More than 24,000 of the 34,720 Nicaraguans who flew into 35 different airports went to just two of them.

By the Missing Numbers

To best understand the totality of the historic mass migration crisis now finishing its third year, the U.S. public would need to see not only the numbers crossing illegally between ports of entry, but also the ones being run through the administration’s new “legal pathways”, which the administration has heavily advertised to the U.S. public and migrants as being managed to various degrees using CBP One system interfaces.

That total understanding would require public knowledge of how many more, beyond those who crossed illegally and were paroled in and outside off the designated management system, entered the United States after their CBP One app appointments at the physical land ports and also those allowed to fly from foreign countries directly to U.S. airports for “family unification parole” releases. Those who fly are required to enter biometric data and other personal information into the CBP One portal as well.

Until those numbers are revealed, public and private institutions will not have the information necessary to prepare for all of the influx.

But the administration has withheld full data for both programs.

For instance, the American public is probably most familiar with the CBP One appointment program rolled out for land ports in early 2023 for mainly Nicaraguans, Cubans, Haitians, and Venezuelans.

But this program actually began nearly two years earlier and has benefited all nationalities, not just those four.

The CIS FOIA lawsuit demands breakdowns by numbers and nationality of every migrant invited over land ports by CBP One appointment who was then paroled into the country, dating to the program’s earliest iterations in 2021.

CIS first discovered and reported on the interface-managed parole program in November 2021, in Reynosa, and that all nationalities without limitation had access long before the administration rolled it out specifically to Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Cubans, and Haitians.

A year later, in November 2022, CIS discovered and reported that the CBP One managed parole program had been quietly expanded, without major media attention, to a dozen land ports, bringing in tens of thousands of migrants a month from Tijuana to Matamoros, Mexico. Those migrant beneficiaries included mainly Mexican nationals, but also Central Americans and Africans.

In the months since the administration announced the program for just the four nationalities, CIS has found many other nationalities using it too. They have included foreign nationals from Dagestan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Belarus, Mexico, and also many nations of South America, Africa, and still, Mexico.