Restoring visas from travel-restricted countries like Yemen, as Biden promises on grounds that Trump’s restrictions are “vile” and “Islamaphobic,” portends a return to the circumstances that brought a radical Houthi rebel fighter into the United States in 2014.

By Todd Bensman as originally published August 27, 2020 by the Center for Immigration Studies

All but lost in political convention news comes a federal indictment of a Yemeni student in Pennsylvania who allegedly hid the fact, from U.S. State Department consular adjudicators in Yemen, that he’d fought with Iran-backed, anti-America Houthi rebels and harbored such fervent hatreds that his Facebook page wished “death to all Americans, especially Jews” and vowed he would stay on the path of jihad.

Because of difficulties in vetting visa applicants and refugees from there, Yemen is among the countries on President Donald Trump’s often misnamed “Muslim ban” proclamation that Democratic nominee Joe Biden has promised to immediately discard “on Day One” should he be elected. The three charges of lying to the FBI against 25-year-old Gaafar Muhammed Ebrahim Al-Wazer (lately of Altoona, Pa.) are the latest of many cases I have reported (and here, here, and here) highlighting that U.S. security vetting systems are garbage-in-garbage-out when running names of aspiring U.S. visitors from Muslim-majority developing countries like Yemen (as well as other countries covered by the travel ban, such as Somalia, Chad, and Libya). U.S.-designated terrorist groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS operate easily and anonymously off all radars in their ungoverned hinterlands.

| Yemen is among the countries designated by President Trump’s often misnamed “Muslim ban.” |

Restoring visas from travel-restricted countries like Yemen, as Biden promises on grounds that Trump’s restrictions are “vile” and “Islamaphobic,” portends a return to the circumstances that brought Al-Wazer to the United States in 2014. Yemen’s embattled capital of Sana’a had just fallen to Iranian-armed Shiite Houthi “Ansar Allah” battalions, which drove the nation’s president into exile and prompted Saudi Arabia to invade — with American backing — in a vicious proxy war that is ongoing. In that aftermath, Al-Wazer applied online for a temporary non-immigrant visa to study English in Austin, Texas, for nine months, the criminal complaint alleges. The young military-aged man checked boxes on his Form DS-160 attesting that he didn’t belong to any clan or tribe and had never served in a paramilitary unit, rebel group, or insurgent organization.

Under the vetting protocol of those years, a State Department consular official at the U.S. embassy in Sana’a interviewed Al-Wazer under oath about his statements on the form. Nothing in the court record indicates the extent to which the embassy at that time investigated Al-Wazer’s background; his fingerprints were probably taken, and the embassy should have run his name and date of birth through the state department’s Consular Lookout and Support System (CLASS) database. But in Yemen, which remains pre-modern in many respects, not much about the population ever gets entered in government databases. Despite warfare and insurrection involving armed groups in the capital that should have heightened vigilance of the embassy staff, Al-Wazer’s application was approved almost summarily on the same day as his interview. Al-Wazer entered the United States two months later, in December 2014, the complaint states.

A Second Bite at the Vetting Apple and Serendipitous Discoveries

With the U.S.-supported Saudi war against the Iran-backed Houthis really raging a year later, in December 2015, Al-Wazer applied for Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a status granted to foreign nationals whose countries are in upheaval, allowing approved applicants to stay (and work) in the United States until they can safely return home (although TPS-holders almost never return). Al-Wazer was living in the Philadelphia area by then, driving for Uber and studying English at Drexel University (the Austin language school plan evidently never happened). An organization called the Arab American Association of New York helped him with the application to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which is an agency of the Department of Homeland Security.

On the Form I-821, Al-Wazer again swore under oath and pain of perjury that he’d never lied on any previous government document and that he’d never participated in any military or paramilitary rebel group, or used any type of weapon against anyone. Again, it’s unclear whether much more happened than a run of his name and birth date through USCIS databases that would not have had any information on him.

A veteran USCIS official familiar with national security vetting at the agency tells me that almost no vetting was done at that time for the TPS applications, and not much more even now.

“That’s about the simplest adjudication you can get. The name and date of birth go through and it’s approved,” the official said. “Unless you’re a criminal, you’re going to get approved. It’s a no-brainer. And even at that, you’d have to be an aggravated felon.”

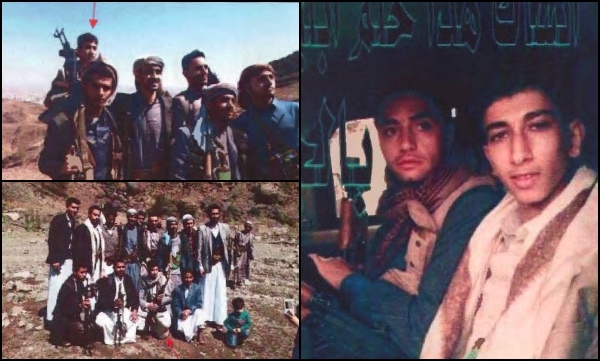

He would have gone on living in the United States, his true heart, mind, and experiences unplumbed, except that six months later, someone at Drexel dimed him out to the FBI. The tipster reported Facebook photo postings showing a heavily armed Al-Wazer and his brother with Houthi rebels, brandishing all manner of weaponry and identifying flags in remote mountainous settings of Yemen with nearby vehicles bearing Yemeni license plates. The Facebook pseudonym Al-Wazer used was “tagged” to the photos and anti-U.S. commentary, and he “liked” them all.

Among the Arabic language conversations that Al-Wazer “liked” was one where the author extolled the Houthi rebels and urged others to join the group in its war against the U.S.-backed Saudi military. One message under a group photo of fighters that Al-Wazer, who was among them, “liked” stated “that these men have taken an oath to stay on their path and … will never be humiliated on the path of jihad,” the complaint said. “The author further wishes death upon the United States and Israel and wishes victory to Islam.”

Al-Wazer allegedly redid his Facebook page at one point to feature photos of himself among Ansar Allah compatriots bearing an automatic rifle and a rocket propelled grenade launcher. On the page, he allegedly wished death to America and Israel for backing the Saudi military effort.

A Return to Pre-Extreme Vetting?

In interviews with the FBI in May 2016, Al-Wazer allegedly tried to keep up the pretenses, not knowing the bureau had his Facebook page, though he did allow that “he hates Saudi Arabia for the continuous bombing of Yemen and further stated that the United States funds the Saudi government and provides it with weapons to continue bombing Yemen,” the government alleges.

The FBI did not arrest Al-Wazer until November 2019 on charges that he lied to the agents about his involvement with Ansar Allah and he was not indicted until this month. It’s unclear why this case has slow-dripped for this many years, but the fact that almost all of the associated court records remain sealed suggests a significant, ongoing investigation that may well involve other actors.

President Trump has promised “extreme vetting” for immigrants and refugees from Muslim-majority countries. And, in fact, security vetting has improved.

More agencies now have access to more databases through which to check the backgrounds of refugee and non-immigrant visa applicants overseas, for instance. In 2019, the Trump administration moved to toughen vetting for all foreign visa applicants by requiring five years’ worth of social media profiles, email addresses, phone numbers, international travel and deportation status, as well as information on whether any family members have been involved in terrorism activity. Data like that might open more vistas on visa applicants’ hearts and minds, perhaps even deterring those who have something to hide in their social media.

Trump’s promised National Vetting Center is up and running, although how it operates and what it has accomplished remains unclear. (CIS has submitted a FOIA request in an effort to find out.)

The USCIS official cited earlier here explained that vetting has improved at the agency:

Every year, we do get better in getting access to things we didn’t previously have before,” the official told me. “We are constantly improving. Refugee programs have gotten better and better and better as time has gone by. Systems that now help us to better corroborate stories.

| Should the current travel restrictions be discarded, more Al-Wazers will make it across U.S. borders. |

But even such improvements would not find terrorist actors in the wilderness regions of countries like Yemen currently on the travel-restriction list, who live entirely off the government radar, when there even is a government. Should the current travel restriction policy be discarded by a new administration, as has been promised, a reasonable prediction is that more Al-Wazers will come knocking on the door and find it wide open again.