Deaths like these have causal roots in American failure to stop and deter mass migration for far too long. It was the American failure to sew up asylum abuse and catch-and-release loopholes at the southern border that, once word of them widely spread to poor countries of Africa, ignited an inexorable and dangerous mass migration.

By Todd Bensman as originally published by the Center for Immigration Studies on October 23, 2019

IN AN ERA WHEN photos of migrant tragedies become emblematic and seize the world by the heart strings comes a boat-capsizing off southern Mexico’s Pacific coast.

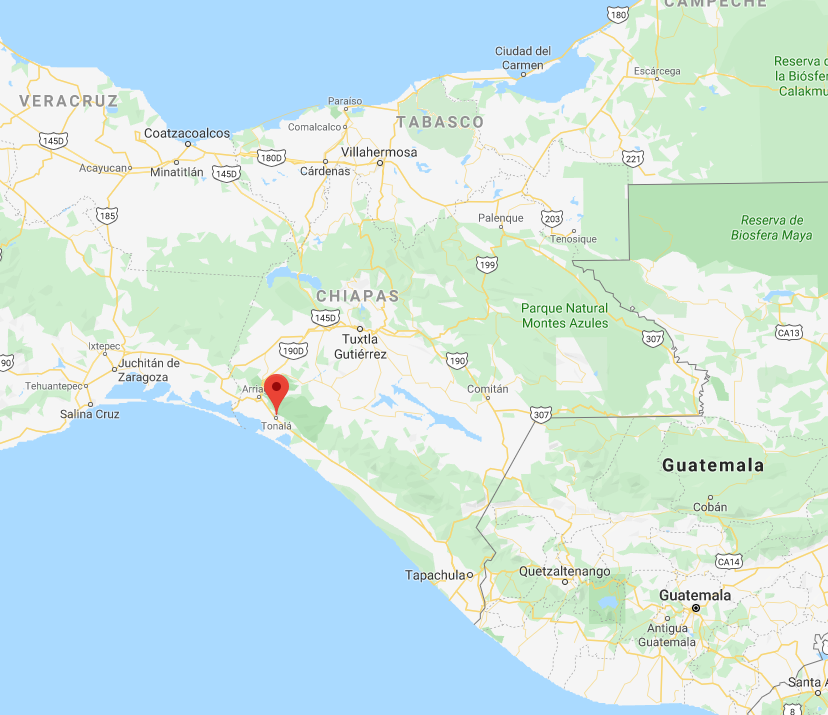

Local news photos show two dead Cameroonian migrants washed up on the sand after a lamentable mishap just off the Guatemala/Mexico land border near Tonalá, Chiapas. Thankfully, the Mexican navy rescued eight other Africans who were on the fishing boat. It’s unclear from local media reporting what happened out there.

Although these photos of drowned Cameroonian migrants have captured limited attention, a message in this wrecked boat nevertheless washed up with them and should be told and heard.

One interpretation will be that President Donald Trump killed these migrants because this summer he forced the Mexican government to deploy 6,000 National Guard troops along the Guatemala border to stop, detain, and push them back on behalf of American xenophobia and racism. Human nature being what it is, as the narrative would go, desperate migrants willing to die to escape their untenable home circumstances naturally went around the Mexican troops at higher risk to personal safety. Bodies on beaches are the inevitable result of decisions in faraway Washington to stop and deter migrants in Mexico.

But another, more layered explanation seems more persuasive. It is that these deaths, and probably many others not reported, had causal roots in American failure to stop and deter for far too long. More specifically, it was the American failure to sew up asylum abuse and catch-and-release loopholes at the southern border that, once word of them widely spread to the world’s poor in places like Africa and Central America just earlier this year, ignited an inexorable mass migration of now a million Central Americans toward the border to get at the American prosperity beyond it. The border collapsed and signaled even more to come in a perpetuating, gathering cycle, this time from all over the globe. Pulled, not as much pushed, by the discovery of gleaming opportunities to Just Get In.

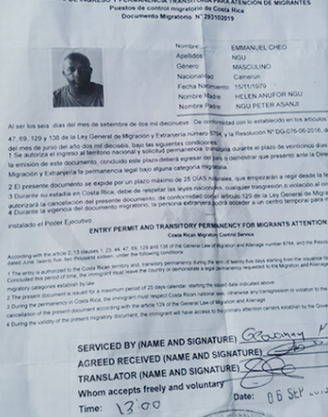

There is strong anecdotal evidence, as I have reported here at CIS, that thousands more Africans than usual this year saw all of this going on with the Central Americans and, on that primary basis, decided to launch their own long journeys to illegally breach and exploit the American border loopholes at this moment of weakness.

Hundreds of such “extra-continentals” moving from South American arrival countries such as Ecuador and Brazil through Panama toward Mexico became tens of thousands almost overnight. Drawn and pulled by the perception that they could take advantage of American brokenness and successfully enter.

These are dangerous trips, similar American gold rushes of yesteryear. In the 19th century, thousands of economically destitute prospectors felt a pull so powerful they were willing to risk death along the Yukon Trail during the American depression of 1893-1898, or the California Trail before then, to reach mythical gold fields. Today, African migrants from Cameroon, Angola, Ghana, and the Democratic Republic of Congo are moving through Panamanian and Colombian jungles, driven by similar impulses, and also dying along the way.

Higher body counts were inevitable, especially when the American government under Donald Trump found itself forced to choose between completely abdicating its responsibility to regain some border management control or acting to intercede in Mexico and with countries as far south as Ecuador, where a great many Cameroonians first arrived. Once Mexican troops were deployed along the Guatemala border, as I predicted in this blog at the time, the smugglers would find ways around them that would include the Pacific Ocean and require Mexican navy patrolling too.

To me, these people are not meaningless numbers. I have personally spent time among Africans and others on their way toward our border. I have interviewed them in Mexico and heard their stories, hopes, and heartbreaks. I know what it would be like to look into their eyes and say “No, you’re not allowed because you did it the wrong way.”

But while their risks, fates, and deaths on the illicit pathways they choose are very real to those of us who have spent time with them, responsible citizens are obliged to pull back and study a bigger picture for its message.

Which is that President Trump’s actions to force Mexican intervention ultimately will, if allowed to succeed over time, save far more lives than will be lost. An inverse correlation comes into play wherein fewer would die or be hurt or have to be rescued from capsized fishing vessels if more are deterred from the temptation to exploit American vulnerabilities at our border. Fewer will die if more are forced to apply legally for entry through safe and appropriate avenues.

The dying will occur less frequently when the naturally alluring American gold fields are made far less accessible than American policymakers let them become.