TAPACHULA, Mexico — The bus braked abruptly and lurched to a stop.

Aamr Bahnan Boles felt his stomach clench as the front door swung open and three uniformed officers boarded, looking none too happy. They had set up a makeshift checkpoint on the highway to this border city in Mexico’s southernmost state, Chiapas.

“Documentos! Ahora!” one of the uniformed men barked. ” Todo el mundo!”

Like almost every other passenger aboard the bus, Boles was a foreigner simply passing through Mexico. But in one way he stood out. An Iraqi, he was the only Middle Easterner on the bus.

Boles was just one of thousands of U.S.-bound immigrants who are have journeyed from 43 mostly Islamic “countries of interest,” where known terrorist groups operate and can presumably deploy infiltrators. Since 9-11, counterterrorism authorities have given this tiny group the label “special-interest aliens,” which triggers a set of security measures reserved just for them. Their ranks have included a number of reputed terrorists.

Boles was a 25-year-old Iraqi war refugee who had fled to Syria, where he had tapped into a smuggling network that enabled him to fly on his own from Damascus to Moscow and then to Guatemala on a tourist visa he’d bought for $750.

After eight months in Guatemala, a different smuggler had gotten him over the Mexican border. In his final push to America, Boles was about to find out that Americans aren’t the only ones who single out Middle Easterners as potential terrorists.

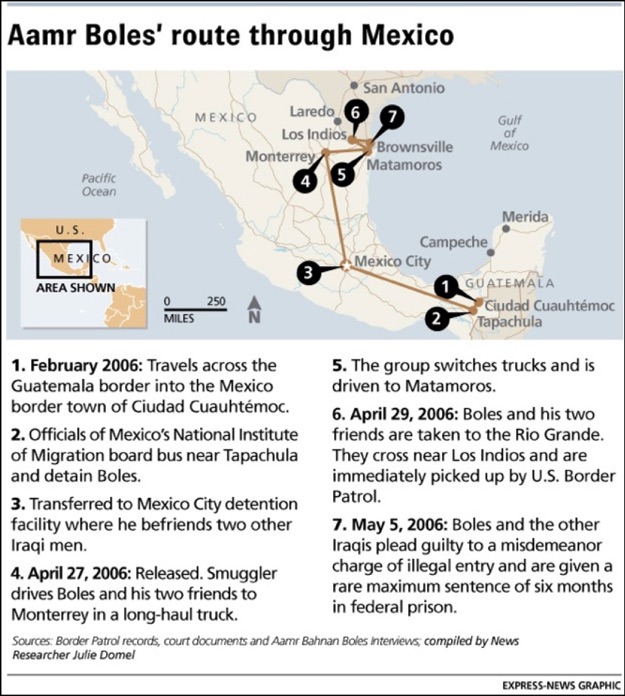

Boles had been traveling for more than two hours since crossing into Mexico from Guatemala. The smuggler had walked his group of mostly Central Americans over the border near the scrubby highland town of La Mesilla. He’d caught the bus on the other side, in Ciudad Cuauhtémoc.

Boles had heard horror stories, true or not, about corrupt immigration officers in both countries who prey on people moving north.

He thought of the $3,000 he kept hidden and how it figured into his plan to hire a smuggler in Mexico. He had been guarding the little bundle with his life since leaving Syria; his entire future depended on it to get him through Mexico.

Now, having been stopped at a highway checkpoint by zealous men in uniform, he feared the worst.

The police asked those aboard the bus to produce travel documents and state their nationality. From some of the foreigners they demanded cash. Boles watched as the money disappeared into the pockets of the uniformed men.

He decided to try lying. With his dark features, Boles hoped he might pass for a Guatemalan. The officers approached.

“Dónde está sus papeles?” Where are your papers?

“I don’t have any,” Boles replied, using Spanish he’d picked up in Guatemala.

“What country are you from?” the officer asked, eyeing him hard now.

“Guatemala. I am a Guatemalan.”

“How much money are you illegally transporting through Mexico?” the officer asked, now clearly skeptical. “Let me see it.”

“I have nothing,” Boles said. “Banditos robbed me at the border. They beat me and took my money.”

“Get out!” the officer ordered, grabbing his arm and pulling.

Outside, two more officers joined the mix.

“You don’t sound like you’re from Guatemala,” the first said to Boles, who now stood surrounded. “I’ll ask you one last time: Where are you from?”

Boles saw no way out.

“OK, OK,” he said. “I am an Arab from Iraq. I’m an Iraqi.”

The confession had an almost miraculous effect. All hostility suddenly melted away. The officers escorted Boles to a spot away from the other offloaded immigrants. The officers huddled among themselves, talking. Occasionally they glanced over at Boles.

A few minutes later, one of them politely escorted him to a black pickup and instructed him to climb in the back. The officer then drove him into Tapachula and delivered him to a detention center run by Mexico’s National Institute of Migration.

The detention center, a few miles from the city’s center, is gleaming new construction, painted an unintimidating mauve and white, with no sign of barbed wire. It’s surrounded by high walls and 10-foot-tall metal gates. Large air-conditioned buses rumble in and out delivering or picking up human payloads.

Most of those inside are from Latin America, especially Ecuadoreans, Cubans and Peruvians who live too far away to be easily deported.

But Boles was taken past them to a special block. He was stunned. All of his new cellmates were travel-weary Yemenis, Tunisians, Pakistanis and Iraqis.

He had become ensnared in the outer edge of a largely unknown American security net, spun out of fear and perhaps a necessary presumption that Boles and his new cellmates might well be terrorists bent on infiltrating the U.S.

But Boles also was in the clutches of another country’s rarely discussed security preoccupation. Mexico’s fear that an attack on the U.S. might originate on its soil had elevated counterterrorism to a top Mexico priority and produced one of the most closely intertwined partnerships in the American war on terror, particularly on the question of special-interest immigrants.

Within a week, Boles and his cellmates would be transported to a bigger detention center in Mexico City, their van flanked by a Mexican security detail, including intelligence officers.

One day, three well-dressed visitors, two women and a man, were let inside to see Boles. He was told they were Americans from the U.S. Embassy, and the Mexican government had allowed them inside to question him.

Mexico’s most unwanted

After 9-11, the U.S. government immediately began urging Mexico to help stop so-called “special-interest aliens” who had moved virtually unmolested through its territory.

Despite public disagreements over illegal immigration by Mexico’s own citizens, the U.S. found a more than eager partner in efforts to stop this one category of migrants from getting to the U.S. border. The main motivation: keeping the billions coming from Mexicans working in the U.S.

Before and after 9-11, top Mexican officials were quoted as saying they believe terror networks had long operated inside Mexico. For example, in May 2001, Mexican national security adviser Adolfo Aguilar Zinser told the BBC that “Spanish and Islamic terrorist groups are using Mexico as a refuge. … In light of this situation, there are continuing investigations aimed at dismantling these groups so that they may not cause problems in the country.”

In January 2002, the Monterrey-based El Norte newspaper quoted National Institute of Migration official Felipe Urbiola Ledezma as saying that “six or seven” known terrorist organizations were operating inside Mexico.

“We have in Mexico people linked to terrorism and we are constantly observing unusual immigration flows … people connected to ETA, Hezbollah and even some with links to Osama Bin Laden,” he told reporters.

Mexican officials have since toned down such talk. In the years since 9-11, Mexico has steadily escalated its cooperation with American authorities on terrorism-related programs. The country has prosecuted smugglers who specialized in moving Middle Easterners, taken steps to guard against corruption in its Middle East-based consulate offices, opened its own terrorism investigations, and passed laws cracking down on suspected terrorist money-laundering operations.

A newly released U.S. State Department Country Report on Mexico’s level of counterterrorism cooperation during 2006, effusive with praise, makes special note of the country’s work diminishing the primary perceived threat there: “terrorist transit and the smuggling of aliens who may raise terrorism concerns.”

“Our bilateral efforts focused squarely on minimizing that threat,” the report stated.

Mexico’s ambassador to the U.S., Arturo Sarukhan, described what Mexico’s interest is: The presumed American reaction to any terror attack from Mexican territory would be abrupt and radical border restrictions, which could catastrophically disrupt the $25 billion in annual remittances that Mexican workers in the U.S. send home and upon which Mexico’s struggling economy has come to depend.

“The day that happens,” Sarukhan said of a terrorist infiltrator who attacks from Mexican soil, “this relationship is over as we know it. Everything. So it behooves my country to ensure that that border is not used as a potential staging ground for terrorist penetration or attack to U.S. soil. Mechanisms put in place by agencies on both sides of the border are providing the results.”

One mechanism, according to government sources in both countries, is a discreet system by which immigration enforcement agencies throughout Mexico, especially at airports, target special-interest immigrants for detention and investigation.

Two American agents with Mexico experience said the U.S. provides the Mexican military with resources for soldiers to set up roadblocks along established land routes close to the American southern border and pluck Middle Eastern immigrants out of the flow.

“Mexico is busting their ass to cooperate on this,” said one federal agent knowledgeable about the programs. “It’s a big deal.”

One particular practice helps illustrate just how close the cooperation is.

Mexico, for the past several years, has allowed American interrogators into its detention facilities to directly question special-interest detainees.

The “threat assessment” interviews, typically conducted by Mexico City-stationed U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agents, occur in the presence of their Mexican counterparts, according to two federal sources familiar with the procedure.

The Americans do not interview every captured special-interest immigrant; they don’t have the personnel, according to one of them.

Instead, the agreement is for Mexican intelligence officers from the National Security and Investigation Center to conduct as many interviews as possible while American agents check terror watch lists and fingerprint databases for them.

American agents can later pick and choose whom they want to investigate themselves, but far from all are.

Sarukhan, not commenting specifically on any particular joint practice, acknowledged that his country routinely relies on the American counterterrorism apparatus in its own ongoing effort to ensure the U.S. is not attacked from Mexico.

“We are obviously receiving intelligence. Mexico is not a player on its own,” he said. “We need that information provided to us by other nations that are monitoring the activities of some of these groups in other parts of the world.”

In Tapachula, a ranking member of the National Institute of Migration, or INM, in the state of Chiapas, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to grant media interviews, said most Arab immigrants, once they cross from Guatemala by land, typically fly rather than cover the dangerous 1,000-mile journey to America by land or rail.

“You’ll almost never find an Arab person walking,” the official said.

That makes things easier for the INM. Many Arab immigrants arrive with money for air passage north. The INM looks for them and regularly catches Jordanians, Egyptians and North Africans at airports in Tapachula and Tuxla, the INM official said.

He said his country’s intelligence agency “checks on them to see if they’re dangerous.” Asked if he’d heard whether any were, he responded: “That information is confidential.”

Not all who have used Mexico to cross into the U.S. have been economic migrants. One of them was Detroit resident Mahmoud Youssef Kourani, a Lebanese national later convicted in Michigan of raising money and recruiting for the terror group Hezbollah.

Federal court records say Kourani was a ranking Hezbollah insider who received “specialized training in radical Shiite fundamentalism, weaponry, spy craft and counterintelligence in Lebanon and Iran.” The government described his brother as “Hezbollah’s Chief of Military Security for Southern Lebanon” who sent Kourani to infiltrate the U.S.

American prosecutors say he got into Mexico in 2001 by obtaining a Mexican visa by paying a $3,000 bribe at the Mexican Consulate in Beirut, then was smuggled over the California border in the trunk of a smuggler’s car.

But Kourani was never caught in Mexico.

American agents familiar with the joint system of vetting special-interest immigrants who are caught in Mexico concede the system is far from foolproof in discerning a terrorist from an economic migrant.

One reason is the FBI has fielded fewer than a dozen full-time agents to Mexico City, and they cannot possibly interview every special-interest immigrant captured there, an official said. Also, the right interpreters are in short supply.

Another problem is that many of those captured have fake papers or no identification, and the names they provide with no verification get run through terror watch lists.

“The bottom line is just because you don’t get a hit doesn’t mean he’s not a terrorist,” the federal agent with Mexico experience said. “You still could be. Fake names are a big problem. I think one of these days something bad is going to happen, and it’s going to have a Mexican signature.”

Senior FBI officials in Washington, D.C., did not respond to phone and e-mail requests to comment about this series.

After the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, as an insurgency against American troops was gaining traction, American agents in Mexico stamped the highest priority on investigating all captured Iraqi immigrants, two sources said.

It was against the backdrop of the war in Iraq and the broad cooperative counterterrorism effort in Mexico that American agents found their way to interview Boles.

Boles is interrogated

Before the Americans got to him, Mexican agents of the National Security and Investigation Center paid Boles a visit in Tapachula first.

The Mexican intelligence officers wanted to know all about Boles. He explained that he was an Iraqi Christian who had fled religious persecution by first going to Syria, and that he was on his way to America to join relatives in Detroit.

The Mexican agents seemed particularly interested in knowing if he did any fighting in the Iraq war and about his time in Syria. The interview was brief.

But Boles was not finished answering questions.

Some days later, Boles was placed in a van with some other Middle Easterners for what would be a road trip lasting nearly 20 hours to Mexico City and another detention facility there. Again his cellmates were Jordanians, Pakistanis and Tunisians.

Not long after, the guards came for him again.

Boles was taken to a well-lit interrogation room fitted with a table, some chairs and a telephone. He faced three interrogators. To the side, a Mexican agent stood throughout the proceedings, observing but not participating.

The telephone was off its hook, its loudspeaker function on. A female Arabic-speaking interpreter was holding. The Americans were polite.

They explained that they had come only to help him and that, essentially, the truth would set him free. He explained once again that his Christian family had been victims of persecution by Muslim extremists.

They asked Boles why he had come to Mexico, how he had gotten there and where he wanted to go.

“I want to go to America. I have an uncle in Detroit. All I want to do is go to America.”

As the hours ticked by, the questions got more specific about names, places and dates related to his time in Iraq and Syria. The Americans scribbled in their notebooks.

Had he served in the Iraqi military? Boles said he had served a compulsory stint. What weapons training had Boles received? Boles said he received the usual but was certainly no fighter. The Americans took more notes.

The questioning then turned again to Syria.

They asked Boles point-blank if he was a member of a terrorist organization that ran a training camp in the Syrian port town of Latakia. According to some press reports, the reputed camp processes foreign fighters on their way to combat American troops in Iraq.

Had Boles ever been to Latakia? What did he know about the terrorist organization that ran it?

Boles insisted he knew nothing about any training camp in Latakia.

After about three hours, the Americans seemed satisfied. But Boles had no travel documents or any other direct evidence of the story he’d given. The Mexicans would hang on to Boles for nearly three more months, possibly to buy the Americans more time to check the story.

Not all of Boles’ cellmates had to wait that long.

One goes to Guantanamo

A variety of fates await special-interest immigrants in Mexico, following investigations of them, often based on recommendations from American agents.

According to Mexican and American sources familiar with the process, those who arouse suspicion are simply deported to their home countries. Boles noticed this as, one by one, his cellmates disappeared.

Information is sketchy about what happens when a special-interest immigrant caught in Mexico arouses greater suspicion.

But at least one U.S.-bound Pakistani captured in Mexico apparently ended up testifying before a military tribunal at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The partial story of the Pakistani is revealed in a heavily redacted hearing transcript that was one of thousands the government was forced to release on a Web site after an Associated Press Freedom of Information lawsuit in May 2005.

One of the government’s allegations was that the Pakistani had close business ties to “an individual known to help coordinate smuggling operations for members of Hezbollah and al-Gama’at al-Islamiyya,” an Egypt-based group.

The prisoner denied knowing about any such smuggling operations and insisted he was merely an economic migrant.

“Yes, I did try to be smuggled into the United States. I was going to find a job to make some money,” the prisoner told the tribunal.

The Pakistani detainee testified that he had taken a plane from Pakistan to Guatemala, and “from there I traveled by foot and vehicle to Mexico.” He recalled crossing some rivers but not much more.

He acknowledged a smuggler helped arrange the journey from Pakistan eight months before his capture on a promise to pay about $18,000 worth of rupees.

“This would get paid when I got to the United States. My father owns a tanker (oil truck), which he would sell to make the payment.”

It’s unknown whether the man remains in detention.

When a detainee arouses deep suspicions, questioning is taken to another level.

A federal source said that at times the Americans have arranged to fly such detainees to their home countries, if cooperative, for intelligence services there to interrogate them. The results get reported back to the United States.

These situations fall short of “rendition,” a recently criticized practice in which American intelligence agents have flown suspects to third countries where they could conduct the interrogations themselves with little accountability, the agent cautioned.

The San Antonio Express-News has been unable to independently corroborate the practice. The FBI did not respond to a query about it.

Some special-interest immigrants who raise no red flags while in Mexican custody are simply released with papers instructing them to leave the country within two weeks.

Boles and two fellow Iraqis he befriended while in jail evidently fell into this category.

After 90 days in detention, Boles and his two compatriots were only too happy to leave the country as ordered. They headed for the Rio Grande and, just beyond its placid brownish-green waters, the Promised Land.

But the long journey of Aamr Bahnan Boles was far from over.