Economics is a modern term inconceivable to a people who still wear animal skins, till small plots of maize, grind millet daily, cook over open fires, and weave baskets. A proposed government dam project at the ancestral center of Himba life, Epupa Falls on the Cunane River threatens a place early explorers once called “The Land of the Red Women”

Update: Nearly 18 years after this article was published, in 2016, the Baynes Hydroelectric Dam project was finally approved and is set for construction. https://www.newera.com.na/2016/06/09/kunene-hydropower-

project-uplift-nation-muharukua/

and Namibia. Photo by Todd Bensman

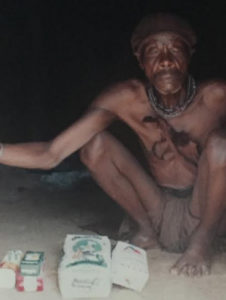

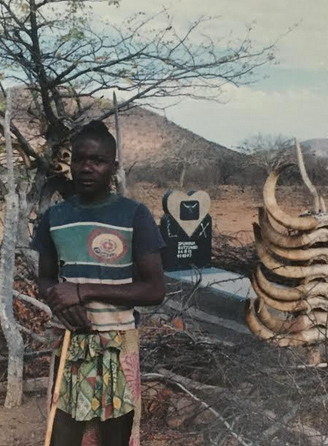

EPUPA FALLS, Namibia – Sacred fires still hold powerful spiritual sway here, and ancestral graves of stacked bullhorns are worshiped. Lean, tough men wearing animal hides and sheathed knives measure their worth in cattle, paper money all but meaningless. The sun and seasons tell time.

Just as they have for centuries, the Himba tribe of northwestern Namibia, a proud nation of perhaps 5,000 nomadic cattle herders, scratch life from this sun-seared wilderness in northwest Namibia – one of Africa’s last successful subsistence societies, anthropologists say. But if the government of Namibia gets its way, a huge hydroelectric dam will be built in their heartland, submerging the Cunene River’s dramatic Epupa Falls and 100 square miles under a sea in the desert.

The Himbas’ rare way of life would be destroyed as they would be forced to resettle, trade their cattle for paper money and suffer thousands of foreign construction workers.

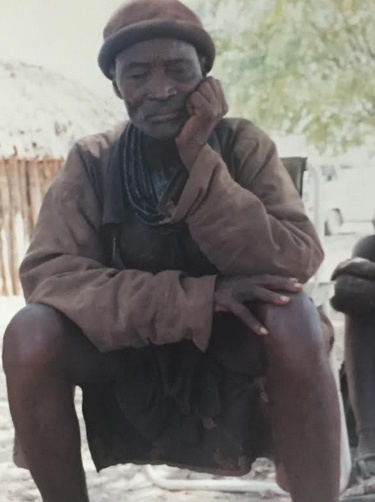

“When you are being killed you have no say, and that is what is happening,” said 72-year-old Katjira Muniombara, a respected Himba elder. Wearing only a groin cloth, he squats on cattle hides in the cool darkness of his cow dung hut, stoking a cow bone pipe.

“It’s going to be the end of the world. It will be the total destruction of the Himba nation.”

The push to build the billion-dollar dam has set off a clash between forces loyal to building a modern Africa and those who would protect what is old and works well.

U.S. and European activists who want the Himba left alone are intervening, turning this rock and scrub brush into an ideological war zone – a dispute that is little known outside Namibia.

Power Struggle

Photo by Todd Bensman

The Namibian government says it needs the dam for electricity to start building a modern economy for its 1.6 million people, and the only Namibian river capable of generating it is the Cunene.

“The hydroelectric potential is there, and this country must grow,” said John Langford, projects manager for NamPower, the state energy company in the modern capital of Windhoek, 600 miles south of the Himbas’ home. Government officials express little concern about a people they regard as impoverished primitives in need of proper jobs and clothing.

“What is so good about being in a primitive state anyway? You don’t think properly. Your mental capacity is not developed. You’re in a bad state physically,” said Jesaya Nyamu, Namibia’s deputy minister of energy. “We are saying, frankly speaking, these people need to develop like the rest of the country, and development will come. They cannot escape it.”

Such talk deeply offends the Himba, who view themselves as wealthy and independent.

“The government says we’re not able to make up our own minds, but we’re not stupid,” said Chief Hikumuine Kapika, leader of the Epupa Falls-area Himba, wearing thick bands of necklaces around his ocher-greased neck. “If we’re so poor, why does the government want to take our land?”

Path to poverty?

Their American friends say disease, discrimination and economic deprivation will surely follow the loss of Himba land and tradition. They would join a long list of subsistence groups destroyed by sudden, large-scale change, human-rights advocates say.

“This dam would destroy the Himba people’s culture and their thriving economy against their will,” said Lori Pottinger, southern Africa director of the International Rivers Network. The group, based in Berkeley, Calif., has waged an Internet campaign against the project.

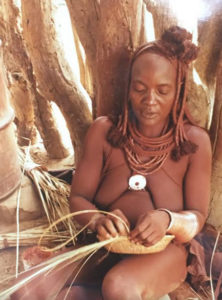

Economics is a modern term inconceivable to a people who till small plots of maize, grind millet daily, cook over open fires, make jewelry and weave baskets.

In a place early explorers once called “The Land of the Red Women,” Himba tribeswomen still smear their bare bodies with a pungent red butter of animal fat and ground ocher rock. Wearing pleated goatskin skirts, they heavily bejewel themselves with bark and copper bangles, seashells and strips of embroidered leather.

The Himba live in scattered encampments of 20 to 30 people, their conical huts encircled by thick brush corrals. They drift with the seasons to new ones in search of water and grazing lands.

Photo by Todd Bensman

Complex social codes govern personal conduct, grazing and leadership. Crime is almost unheard of. Traditional medicine women heal.

Elaborately sculpted hairstyles show a person’s age – two forward-hanging plaits for adolescent girls, a mohawk braid for boys.

The idea to build here dates back 60 years. The democratic government headed by President Sam Nujoma aggressively resurrected it after Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990. His government was eager to wean Namibia from costly imported South African electricity and make jobs for voters.

Completion of a dam feasibility study in December has cleared the way for Mr. Nujoma to approve the project and seek foreign investment. The $7 million, 3-year study, funded by Scandinavian aid agencies, concluded that an Epupa Falls dam was the most economically feasible, while acknowledging social and environmental costs.

Tensions with the government have been on the rise since Chief Kapika toured European capitals in 1997 to urge investors and political leaders not to back the project. The trip angered Namibian officials.

Police have forcibly broken up meetings between Himba leaders and their legal advocates. In a speech last summer, Mr. Nujoma angrily threatened to deport the “white foreigners” who have come to fight the dam.

“We are warning you for the last time – don’t disturb the peace in Namibia!” the president said.

Extravagant government gifts offered to Chief Kapika – a speed boat for the Cunene and a new red pickup truck – have complicated matters. The chief, who accepted the gifts, insists, “Nobody is telling me what to say” because of them.

Mr. Nyamu, the deputy energy minister, denied trying to quiet the chief with gifts but conceded he “would certainly not cry” if they softened Chief Kapika’s hard line.

Neighbor’s concerns

But obstacles beyond Chief Kapika threaten the dam.

Construction is unlikely without the cooperation of a peaceful neighboring Angola, on whose territory half the project would sit. But the country has been at civil war again in recent months, a 4-year-old peace accord with rebels in tatters.

Even if U.N. diplomats restore the accord – and investor confidence – it remains unclear whether Angola would OK the dam project. Several Angolan officials involved in the dam study said they oppose it on humanitarian grounds.

“When you talk to the Namibians, they only think of money and economics,” said Joao Serodio de Almeida, Angola’s environment minister.

“The Himba people aren’t important because they’re so few. Well, these people are happy. What right do we have to evict them?”

But Mario Gomes da Silva, an Angolan power company executive who co-chaired the study committee, said such objections may not count. “The final decision will be a political one.”

Already changing

Meanwhile, a sword of Damocles hangs over the Himba people. There are signs that even the prospect of a dam is changing them, as contact with foreigners and their material seductions increases.

Tribespeople near dirt roads now swamp visitors with outstretched hands, begging for processed foods. Alcohol traders have done a thriving business in the Himba outback. Empty beer bottles pile up amid staggering men in some villages. T-shirts are appearing.

A Norwegian aid worker won government permission to import mobile tent schools that follow Himba camps with Western ideas.

“I will quit this life for good and go away,” said Ripuruavi Mgombe, 22, a shepherd attending one such school recently. “I want to live like white people. It is very interesting.”

Margaret Jacobsohn, an anthropologist who wrote a book about the Himba, acknowledged that the tribe is changing. But they should have the right to make choices, one of those being the traditional ways that have served them so well through the centuries, she said.

“The Himba will change, no doubt, but if they are allowed to change, it should be at their own pace,” she said. “Let’s not destroy this system. Let’s learn from it.”

Older Himba say they’ll hold the line, angered by government suggestions that they need a helping hand.

“We are rich. We have everything,” said Chief Kapika, sitting regally on a metal lawn chair under a tree, his subchiefs seated on the ground around him. “The livestock you see are fat, the land around Epupa Falls green. No! If they want to kill us, they have to drive over all of us with their bulldozers!”