By Todd Bensman as originally published April 27, 2022 by the Center for Immigration Studies

AUSTIN, Texas – Having covered the politically taboo threat issue of Islamic terrorist border crossings and even written a book about it, I have long had to contend with ungenerous government agencies that jealously guard all information about it from public disclosure.

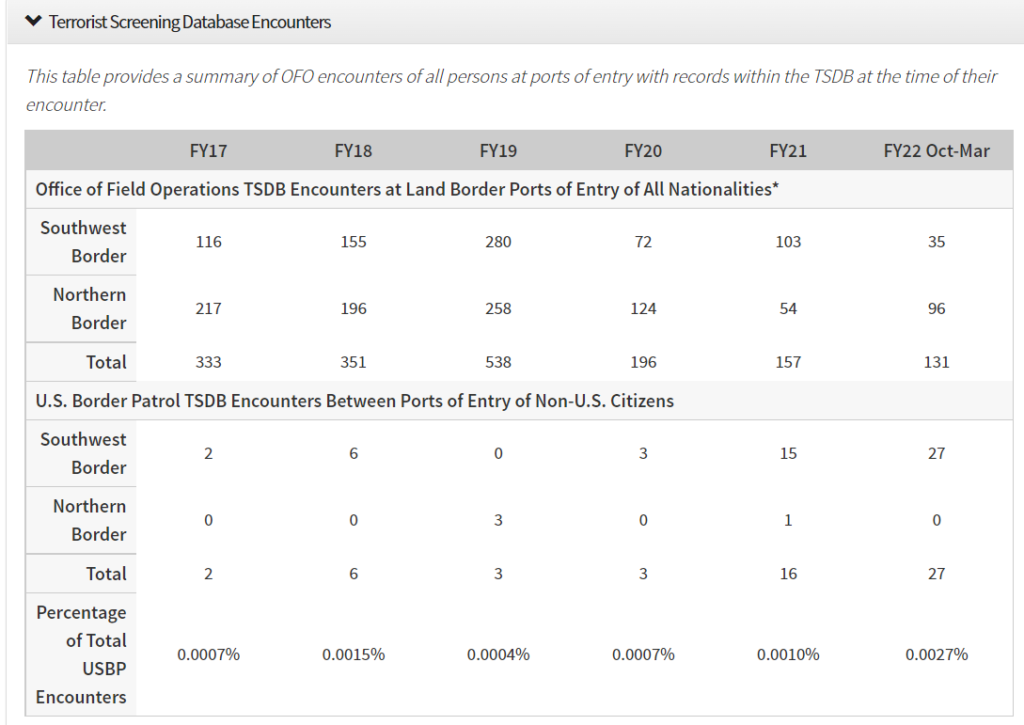

So few other people could have been more surprised to find a brand new line item section on the U.S. Customs and Border Protection “Enforcement Statistics” page titled, “Terrorist Screening Database Encounters.” In other words, there’s now a public page where any American citizen can, for the first time, go to see the number of times federal agents have encountered an immigrant at both northern and southern land borders who was on the FBI’s terrorist watch list.

One way to measure the significance of CBP providing such raw information to the general public is that, in the recent past, major American newspapers and television networks have staked their reputations on insistence that no terrorist suspects ever cross the border and that anyone who says otherwise, like former President Donald Trump did in 2018, is a big fat fear-mongering, racist liar. Otherwise, they refuse to report government evidence when it does make it to the public.

The controversy over whether terrorist suspects cross the land border has left many Americans confused over the years as to what is and isn’t a phony political narrative about this one of many border threats.

And yet there it is now in black and white on CBP’s public-facing statistics page right between “Gang Affiliated Enforcement” and “U.S. Border Patrol Recidivism rates.”

The statistics page can be improved. It lists just the raw numbers of encounters per fiscal year of Known or Suspected Terrorists (KSTs) who showed up at a border port of entry, like a bridge over the Rio Grande, and also between ports of entry, meaning illegal entry by someone Border Patrol agents had to go catch. Further breakdowns would be helpful.

The two categories differ significantly in meaning and implication.

Ports of Entry Encounters

From the provided data, you can’t read too much into the numbers at a controlled port of entry. These might, for instance, be individuals who drive a long-haul truck back and forth from Canada to Detroit, flagging on the database multiple times a week, or an American importer who frequently moves between Nuevo Laredo and Laredo. So those numbers are way higher than the ones reflecting illegal border crossers.

“POE totals may include multiple encounters of the same individual,” the new section notes in the postscript.

Most hits at the POE probably are not foreign nationals without legal status from beyond Canada, Mexico or the United States. They may be Canadians or Americans or Mexicans who have legal status to travel back and forth, thus not overtly trying to run and hide as terrorists. (As a quick aside, agents see the watch list flag on their station’s computer screen and report the encounter and any other observable details back to the FBI Screening Center without letting the traveler know they flagged. The intel very helpfully goes straight to the case agents working the investigations).

Perhaps more concerning might be POE encounters with unfamiliar fresh foreign national travelers on the terror watch list who shows up for a first time to claim asylum, which will raise bigger alarms (and isn’t supposed to work out well for the asylum claimant). These individuals are usually denied entry.

The new statistics page doesn’t break any of this down but CBP might consider doing so later for greater clarity.