UN-organized ‘cash working groups’ are key to new White House border-management plan that pre-legalizes immigrants before they can jump the border

By Todd Bensman as published January 9, 2023 by the Center for Immigration Studies

MONTERREY, Mexico – The director of this country’s largest immigrant shelter worked himself into a peak of outrage recalling the largesse of a United Nations program that, unknown to most Americans, has been showering millions of dollars in cash to help foreign nationals on their way to cross the U.S. southern border.

Casa INDI shelter director Jose Jaime Salina Flores was recounting the recent case of an immigrant mother staying with three daughters at his facility who demanded that Flores help arrange a UN raise above the 6,000 pesos a month the UN already gave her on a debit card (about US$300) and which she thought insufficient while she planned the journey over America’s border.

But Flores recounted in a recent interview with the Center for Immigration Studies what he told her and why her sense of entitlement so irked him.

“I said, ‘Tough! Millions of Mexicans wish to earn that amount of money per month right now — working — and she’s having it for free when she’s not paying anything for shelter, food, and medical attention,” the Casa INDI shelter director, otherwise a passionate advocate for migrants, recalled, his voice rising in anger. “She pays absolutely nothing and on the side she gets 6,000 pesos and still she’s complaining it’s not enough?! Lots of Mexicans would like to have that!”

In his irritation, Flores would find unlikely common cause with some of the few Americans who know about this UN cash giveaway program, which is widespread and provides tens of millions of dollars to hundreds of thousands of immigrants on their way to illegally cross the American southern border.

In late 2021 and early 2022, the UN program drew outrage among advocates of regular immigration law enforcement, including congressional Republicans of border states, after they learned, in part from Center for Immigration Studies video, photos, and analysis, that UN debit cards and vouchers for transportation, shelter, and medical and legal advice to gain asylum “protection” all along Latin America’s migration trails were easing travel in the most voluminous ongoing mass migration in American history. One group of 12 Republican lawmakers in the House of Representatives, led by Texas Rep. Lance Gooden (R), last year proposed legislation calling for the United States to defund the United Nations for ironically, to them, using American tax money to inflict what they see as a catastrophe on Americans who pay those taxes.

But as White House border policies drive the crisis into a third escalating year, the same UN-led constellation of non-profit migrant advocacy groups have posted plans to keep this hemispheric-wide, migration-sustaining cash giveaway program going in 2023 and in 2024, according to a revealing planning document recently published online that has drawn scant, if any, media attention.

The “Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan” for 2023-2024, coordinated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM), both of which receive substantial annual U.S. taxpayer contributions, calls for a quarter of the $1.72 billion it wants for 2023 — some $450 million — to go directly as cash or cash equivalents to “migrants and refugees” on the move throughout Latin America.

All the planning and money handouts happen under the UN-coordinated “Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants”, a network of some 228 non-profit entities and religious institutions established in 2018 that hands the money out or delivers other comforting, perhaps even enticing, services (p. 268 of the downloadable report lists the current participating organizations and their “financial requirements”).

“Cash Working Groups” made up of more than 50 of the non-profit migrant advocate organizations will distribute the $450 million as “Cash and Voucher Assistance” (CVA) or “Multipurpose Cash Assistance” (MCA) to those paused outside their home countries and contemplating journeys or actually moving already along the migrant trails in 17 countries from South America through Central America and Mexico, the planning document reveals.

The $450 million for 2023 is less than 2022’s $518 million. But its latest regional plan for Latin America still sees a heavy role for cash support this year and in 2024 because historic numbers of Latin Americans are migrating north, along with many other nationalities.

Host governments “continue to offer protection, humanitarian assistance and socio-economic integration opportunities to millions of refugees and migrants from Venezuela”, the document says. However, it also points out that something new is pulling them from their relative comfort in host countries toward the United States “notwithstanding this generosity”, the document notes, making no mention of DHS allowing hundreds of thousands into the country. “An increasingly sizable proportion, including those of other nationalities, have increasingly resorted to onward movements.”

A key tactical response is that “special attention will be given to the use of CVA for in-transit populations, including the need for comprehensive solutions throughout the journey,” the document states.

Published in mid-December 2022, the new document warrants attention because it provides a rare, fairly detailed glimpse into the migration-support activities of the United Nations and the migrant advocacy organizations, which last year drew angry political criticism from some in the United States who have perceived that it was helping to facilitate a mass migration event that broke every border-crossing record in American history over a 24-month span. (For the UN’s response, see the CIS blog post “In Mexico’s Deep South, the United Nations Explains Handing Cash to U.S.-Bound Migrants”.

The issue of United Nations-led migration support activities in Latin America is almost sure to erupt in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives this year.

Asked to comment about the new planning document, which he had not yet seen, for instance, Gooden said he was outraged to hear of their continuation at such high levels. Gooden was strongly considering again proposing his bill to defund the UN, with new revisions.

“This is a slap in the face to American taxpayers who foot the bill for this corrupt globalist institution,” he told CIS over the weekend. “Republicans must condition UN funding and stop this taxpayer funded invasion immediately.”

Above all else, the UN investments in migration support activities this year now matter because they may well have just become the central linchpin in a new, unconventional White House border management plan to essentially “legalize” hundreds of thousands of immigrants annually before they can attempt illegal crossings so that they can instead be escorted into the country through official ports of entry, with pre-approval, as CIS reported here in November.

That questionable game plan, should it survive a current federal legal challenge by Florida, will almost certainly create lengthier wait times throughout Latin America for immigrants who may well only choose it if they know they can count on UN cash and aid while they wait.

Arguably, the new Biden plan would have far less chance of success if participating immigrants thought they would have to financially support themselves during their long waits in the queue.

Breaking It Down

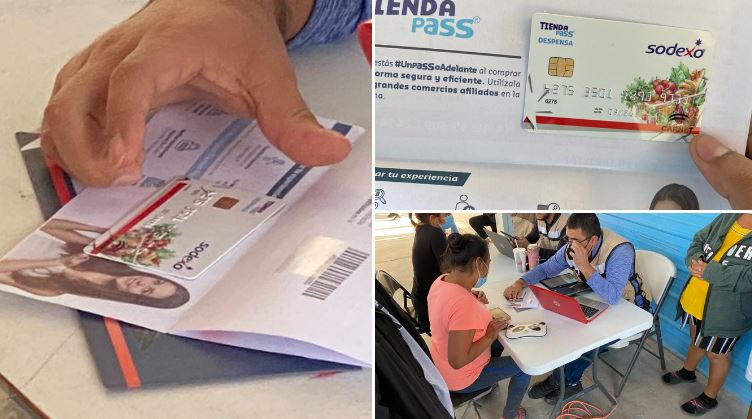

Of the $450 million, $149.5 million would be given out in cash or debit card form to 631,000 “in-transit” immigrants moving mostly northward, about half of the 1.2 million the group estimates will be on the march this year.

Those who get a piece of that $149 million will spend it with debit-like cards with few restrictions. Monthly auto-deposited amounts are often pinned to a region’s cost of living index, so tend to be higher in northern Mexico than in southern precincts or Central America.

Like the cash card that Nicaraguan national Marvin Martinez Ceneno showed the Center for Immigration Studies on December 30 at the Casa INDI shelter in Monterrey, one of Mexico’s largest. The 55-year-old single man traveling with no family members qualified for 2,000 pesos a month (about US$100), which helped him avoid having to return home until he can organize a probably smuggled trip over the American border at a convenient time for himself.

Asked where he is able to spend the money on his card, Martinez answered, “On the pharmacy and everything. Food and clothes. They deposit you every month 2000 pesos.” He quipped, “But you cannot buy liquor. And no cigarettes.”

Meanwhile, $302 million in vouchers would be granted to in-transit or potential immigrants in 17 Latin American countries and used to pay for lodging and a laundry list of other road-ameliorating programs, like $25 million for “humanitarian transportation” along the migrant trails.

The document explains that it would pay “long distance transportation” costs for 158,700 migrants and refugees who need to move within a country from “isolated and/or border areas” to other border crossings or areas where they can access “healthcare and protection, and to institutions to regularize their situation and/or access documentation” so that they may “continue transiting to where they can safely access a third country regularly”.

“These activities will promote safe, dignified and informed movements that mitigate protection risks on the roads and in the provision of goods and services,” the document states.

The document calls for another $130 million to help shelter 586,500 people in the 17-nation region. “Cash transfer programs” will pay, in part, for “immediate emergency shelter needs of refugees and migrants along the borders and in isolated areas.”

What kind of shelters?

Collective ones, but also hotel and hostel rooms for, among others, “thousands of refugees and migrants in-transit towards the U.S.” Other monies will support rent and utility payments.

Other monies will fund lawyers and legal services to help traveling immigrants access “protection”, meaning asylum or humanitarian parole offered by the United States. “CVA interventions will cover the costs related to accessing legal documentation or regularization services” in Mexico, for instance, evidently for the legal trainings and services that are going to “support refugees and migrants in accessing asylum and migratory regularization pathways”.

Republicans Ready to Rumble over U.S. Taxpayer Funding

House of Representatives Republicans, especially some in the right-wing Freedom Caucus, are not the only ones spoiling for a political confrontation about non-governmental organizations facilitating mass illegal migration over the border. In December, Texas Governor Greg Abbott wrote Attorney General Ken Paxton asking him to investigate whether non-governmental organizations unlawfully assisted mass border crossings that overwhelmed the El Paso region.

“In addition, I stand ready to work with you to craft any sensible legislative solutions your office may propose that are aimed at solving the ongoing border crisis and the role that NGOs may play in encouraging it,” Abbott wrote.

But recent outrage over revelations that U.S. tax money is being funneled through UN agencies and affiliated NGOs to facilitate mass illegal immigration has breathed some new life into an old movement to cut off U.S. tax money to UN agencies. How much the U.S. contributes annually and how that money finds its way to the UN’s 15 specialized agencies is difficult to see due to highly opaque accounting at several junctures.

Recent Congressional Research Service reporting reminds us that the United States has been the largest financial contributor to UN entities since the UN was established in 1945. Congress and the executive branch play key roles; Congress appropriates U.S. funding, while the executive branch shapes where the money will go through the State Department and the U.S. Mission to the United Nations in New York City.

The Biden administration’s 2023 budget requested about $4.5 billion for UN entities and about $10 billion in 2022 for humanitarian assistance that would “support vulnerable people abroad”, but it’s unclear where it all ends up. The most recent data available shows that the U.S. contributed about $5.87 billion to UN entities in FY 2020 that deal with migration and refugee assistance.

The new UN strategy document, however, says the United States and the U.S.-supported UN are far and away the largest contributors to the new response plans, with a combined funding of more than $765 million in 2022.

Of that, the U.S. gave $391.5 million.