In November, a writer for the American Thinker called to ask for my recollections about covering the trials and tribulations of what is often described as the largest terrorist fundraising operation in U.S. history. It hadn’t occurred to me, but the 10-year anniversary of the “Holy Land Foundation Five” convictions in a Dallas federal courtroom has unexpectedly arrived.

The call from the American Thinker triggered even older memories related to the Holy Land Foundation case, and of the related case against Infocom Corporation: I had become one of the first U.S. targets of Islamist “lawfare,” a term reflecting the tactic of filing high-expense civil litigation to silence and delegitimize opponents. I had been placed on a Muslim community “blacklist” and labeled a Muslim-hater for doing my job. I remembered feeling shocked and betrayed by having seen, for the first time up close and personal, how a pressure campaign by criminal suspects could, like a paper cup, collapse the journalistic ideal of truth-telling.

HLF, Infocom, and everyone connected to them are gone, still in prison, or deported. But long before any of us who played bit roles could even have predicted such outcomes, in 1999 and 2000, the HLF and its supporters were on a war footing. They were fighting a public relations influence campaign to keep the millions flowing to its coffers and (as would be revealed later) then to “zakat committees,” which would launder the cash to Hamas’ arsenals and the families of suicide bombers. I was a young reporter at the time, just assigned to cover federal courts and the FBI for The Dallas Morning News. By then, the Morning News’ Steve McGonigle (now unfortunately deceased) and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Gayle Reeves had broken stories about suspicions that HLF was actually Hamas’ clandestine fundraising arm in America, and that a massive FBI counterterrorism investigation was underway. Steve had been sent to Israel at one point to report on evidence and intelligence collected there on connections to HLF in Dallas.

Financial investments in travel like that reflected an early commitment by the newspaper to a legitimate public interest news story. It wouldn’t last.

My own exposure to this young phase of the HLF story became unavoidable after I got my Dallas FBI/federal courts assignment in 1999. It happened that, just then, HLF and a nationwide network of Islamic advocacy groups had been ramping up a strategic campaign to shut down any further news coverage by hawking a narrative of religious discrimination. A narrative that bigotry had driven the newspaper and the federal government to baselessly persecute a charity interested only in helping Palestinian women and children, or Kosovo war refugees.

More than once during this time, I saw delegations of HLF leaders and suited-up lawyers caravanning through the newsroom to meetings with senior editors. I don’t know what was said in these meetings. But I do know that Steve complained to me privately many times that, as a result of these meetings, he was banned from ever writing anything about HLF again.

He was bitter about the writing ban at the time because in his view it revealed a lack of commitment to journalistic integrity, faint hearts in the back office, and unforgivable concessions to probable terrorists based on a persecution claim about him that he knew was spurious. I know from conversations with Steve, who was not Jewish, that he was not particularly interested in the Israeli-Arab conflict and certainly not emotionally invested in it. To him, a charity raising tens of millions of dollars in his backyard, under false pretenses to donors, to cover for supporting terrorism in another part of the world was just a damned good story.

My FBI sources — both line investigators and management — were aware that something had happened at the newspaper and were highly curious. Often, they would ask me: What ever happened to Steve? Eventually, they told me Steve himself had explained to them that he’d been pulled off the story under pressure from the criminal suspects. It was embarrassing. I would look down, shrug, and change the subject, because if Steve wasn’t writing them, then why wasn’t I?

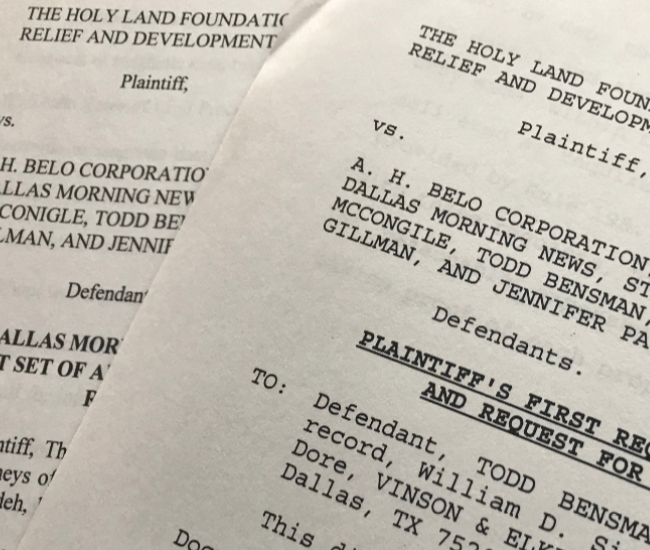

If any legal threats were made in those meetings with our editors, HLF soon followed through to cement the blackout. In early 2000, Steve and I were named as defendants in a libel lawsuit along with two other reporters. The other three of us happened to be Jewish, although this obvious coincidence was never discussed out loud in mixed company at the paper.

I believe I was sued not because of any story I had written about HLF (I had not written any at that point), but because I was positioned to write about HLF based on my covering the FBI, and because I was, to them, a potentially pro-Israel Jew. In fact, the lawsuit claimed I was anti-Muslim because of other investigative stories I had recently written about how local Muslims had mustered to send weapons to the Kosovo Liberation Front in 1999 (possibly illegally), and about benefits fraud among some Muslim Kosovo refugees resettled in the Dallas area.

The lawsuit had its intended impact. We were all told there would be no writing about HLF during the litigation for fear of creating aggravating new points of argument, which of course went on and on and on. That was the point. That is called “lawfare” today, although at the time we all knew exactly what it was.

Big money clearly backed that lawsuit. Motion after motion was filed, each requiring exhaustive responses, which were met by responses on the other side, and so on. In-house, I was subjected to meeting after meeting with the company lawyers. I had to hand over notebooks and answer interrogatories point by point. Meanwhile, an HLF-backed website covering our reporting on all things Islam put a “blacklist” together of reporters whom no one in the Muslim community should ever talk to if contacted. I was placed on that list along with Steve.

Picketers kept the pressure on, too. They showed up with signs for months on end every day at lunch. Many of the signs named Steve and called him names.

After probably 18 months of this, in about the summer of 2001, an out-of-court settlement was in the offing. We were told everything had pretty much been hammered out in a document. I never saw that settlement document, but all of us heard that it was going to allow a group of local Muslim activists to know ahead of time what we were going to write about anyone Muslim, especially the HLF. And we were to show a committee of community people the stories in advance to ensure they didn’t “libel” Muslims (and, according to our speculation, to open opportunities for new litigation threats if they didn’t get their way with our stories). If this outrageous settlement rumor was true, the chilling effect would have been legally imprinted on future coverage, quite possibly in perpetuity, and set a terrible precedent for American journalism. I still wonder what the draft of that settlement said.

Just on the verge of final signings though, 9/11 happened. The suit was closed.

By December, President George W. Bush designated the HLF a terrorist entity in a Rose Garden announcement, seized all of its assets, and charged all of our tormentors with terrorism crimes.

A lawsuit with us was the least of their worries now. In effect, the 9/11 terror attacks rescued us to report again, honestly and free of restraints. Only then was I free to write about the case as it made its way through criminal and immigration courts.

I left the newspaper in 2003 and continued covering all of the HLF and Infocom cases for CBS News. I wrote stories which I’m positive would never have been allowed to run in the newspaper a few years earlier — like this one documentinghow defendant Mufid Abdulqadir, the half-brother of Hamas supreme leader Khalid Mishaal, was a singer in an Islamic hate band that passed the plate for Hamas at super-weird performances. I reminded the public that HLF would never end because two of those indicted fled the country ahead of their arrests, including a cousin of Mishaal, and remain international fugitives.

Let no one say HLF and Infocom weren’t Hamas entities, as people still do. In addition to two of the defendants having direct family connections to Khalid Mishaal, one of the fugitive defendants in the Infocom case is none other than former Dallas resident and company founder Musa Abu Mazook, who remains openly one of Hamas’ senior leaders. Also let no one say that Islamist “civil rights” groups don’t still exercise this kind of pressure on American news operations. I’ve seen it time and time again over the years from a private place of deep familiarity.

On the 10-year anniversary of the Holy Land Five convictions, I wonder if the main lesson learned was that pressure from such “advocacy” groups worked and worked well.