Perhaps an unauthorized work-around to limits on asylum or work visas

By Todd Bensman on November 3, 2023

AUSTIN, Texas — Of all the revelations from a recent Center for Immigration Studies Freedom of Information Act lawsuit none was more surprising than that the U.S. government allowed the entry of more than 57,000 Mexican nationals through the secretive CBP One smartphone app scheme that permits aliens to, in effect, schedule their illegal immigration through a land port of entry.

The administration presented the phone app “legal” crossing program as a way to better manage the in-flows of presumably persecuted people in dire need of a temporary humanitarian entry from dangerous home countries like Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Haiti, and that they would all probably apply for asylum in America soon. The administration authorizes recipients for two-year renewable work permits.

“Only noncitizens who can be considered for a humanitarian exception may use CBP One,” the administration announced in a January 2023 White House order. “Under this order, CBP is authorized to accept individuals on a case-by-case basis, based on the totality of circumstances, including considerations of humanitarian interests.”

But the United States has never before considered Mexico so dangerous that it would grant such broad swaths of its citizenry humanitarian protection (with work permits). Because Mexico’s government is not considered a political persecutor or interested in torturing its citizens, very few Mexicans bother even to apply for asylum or protection under the Convention Against Torture; immigration judges reject the claims of those who do apply about 96 percent of the time.

That’s why experts on Mexico and the U.S. asylum system, upon learning that 57,000 Mexicans were deemed eligible for the CBP One app humanitarian parole since May 2021, were flummoxed to learn that Mexicans were the top recipients among 250,000 from nearly 100 other countries granted the land port crossing benefit, CIS’s October 24 report from FOIA records showed.

“If true, I find this figure shocking, bizarre, and absurd, not to mention flatly inconsistent with our nation’s immigration laws,” former ambassador to Mexico Christopher Landau told me. “As a lawyer, a former US Ambassador to Mexico, and someone who knows that country well, I cannot fathom any legal or factual basis for granting such extraordinary relief en masse to so many Mexican citizens.”

Andrew R. Arthur, a CIS colleague who served as an immigration judge for nine years, who was obliged by congressional statute to reject Mexican asylum and Convention Against Torture claims during his tenure, was no less perplexed over the revelation.

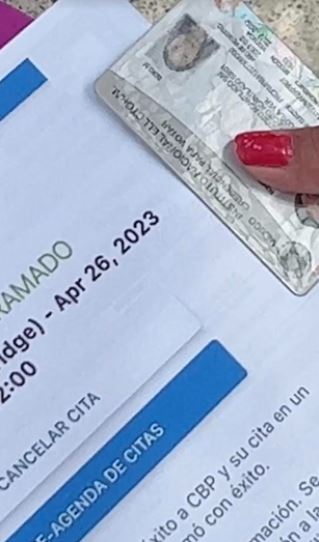

Mostly Mexicans await their CBP One phone app crossings in Tijuana, Mexico. November 2022 photo by Todd Bensman.

“The whole purpose of the scheme is to allow people to file protection claims on humanitarian grounds,” Arthur said of the CBP One entry scheduling app. “But few if any Mexicans ever have valid claims for U.S. protection. There’s nothing that suggests the Mexican government either tortures or acquiesces in the torture of its own nationals. And so, it makes no sense whatsoever to allow 57,000 Mexicans to make those claims.”

Biden’s U.S. Customs and Border Protection has not responded to a CIS request emailed this week — or others emailed in November 2022 when I first discovered Mexicans were program beneficiaries — to explain in writing or in interviews why the administration has allowed so many Mexican nationals to cross through the ports on ostensibly humanitarian grounds.

Notwithstanding Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), who penned a demand letter pressing the administration for a spectrum of answers about another CIS report that Biden’s DHS cleared for port crossings more than 7,300 foreign nationals from 24 nations of national security and terrorism concern, no other lawmakers, media outlets, or researchers are known to have asked about the 57,000 Mexicans. Absent any explanation, experts are left to speculate.

An Unauthorized Work-Around for Mexican Asylum?

One idea is that the Biden administration has unilaterally decided to expand the U.S. asylum law — outside the sole authority of Congress to do that.

“It just doesn’t make any sense,” former CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan told me he first thought when he saw the CIS report. “Normally, Mexican nationals never claim or get asylum because they know they’re not going to get it. My only thought is that Mexicans started waking up to the fact that this administration is giving it to them now this way, that the administration is expanding the statutory limitation of our asylum laws that Congress clearly spelled out, and just not telling anyone. I wouldn’t put that past this administration to do something like that.”

Indeed, Morgan may have something there.

U.S. asylum law requires immigration judges to grant it on five grounds: that they have suffered past persecution or have a “well-founded fear” of future persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group, and that their home government either can’t or won’t protect them.

Years of rulings have established that suffering the depredations of crime and gang violence does not qualify one for asylum, especially because Mexico is a large country of 761,000 square miles where people can easily move internally to safer locations, much as Americans move from high-crime areas to low-crime areas without the need to flee to other countries.

I learned about Mexican ineligibility for asylum while reporting on the brutal drug war in Mexico from 2006 through 2009 for a series of stories about Mexicans fleeing cartel violence north over the U.S. border, only to find asylum legally out of reach. Some of these crime victims included bleeding, wounded police officers who, despite sympathy for their tragedies in immigration courts, still found that any reading of the law prevented judges like my colleague Andrew Arthur (some of whose Pennsylvania cases I detailed) from granting them asylum.

Some Evidence in Support of Ad hoc Asylum Work-Around Theory

Some small support for the theory that Biden’s appointees have pursued an unauthorized work-around for these asylum law limitations comes in the form of interviews I conducted with several Mexican men and women with young children while I was in Mexicali, Mexico, in November 2022. They were inside a municipal government shelter checking in on the CBP One interface for their scheduled escorted deliveries to CBP on the Calexico, Calif., side of the port of entry, as detailed in this report for CIS.

When I asked them on what grounds they thought the Americans had granted them this “legal” crossing benefit, the Mexicans told me they just told the Americans they had lived in areas of Sonora, Baja, and Jalisco states where cartels had recently been fighting.

Arthur posits that maybe the Biden administration has secretively created a way around U.S. asylum law restrictions for Mexicans, which he found potentially consequential.

“More than 126 million people live in Mexico,” Arthur said. “Under this scheme, the border between the U.S. and Mexico is effectively erased. And if the Biden administration is simply allowing in any Mexican national who wants to enter the U.S. without screening them for asylum, there is a virtually limitless population of inadmissible Mexican nationals who could be allowed to come in to live and work here indefinitely.”

Morgan also sees a potential population transfer in the offing if this theory turns out to be what is happening.

“This actually could be a very significant story,” he said.

An Unauthorized Guestworker Program that Allows Tax Evasion?

My own working theory is that the Biden administration has used its CBP One entry scheme to secretly establish a new de facto work program for Mexicans without congressional authorization.

Mexico and U.S. industry have long coveted guestworker programs, such as the H-2A and H-2B nonimmigrant temporary visas, which Mexicans use more than any other nationality.

The H-2A visa is for unskilled, non-farm labor which allows holders of those visas and their employers to avoid payroll taxes to the government, CIS Fellow David North explained to me. H-2B work, on the other hand, is covered by the usual payroll taxes, that are about 8 percent of the payroll for the employer and another 8 percent for the workers.

But no one likes that visa because of its tax obligation, and so with the historic mass migration surge, the number of employers seeking H-2B workers has sharply declined, North recently wrote. That visa is capped at 66,000 workers a year, but the State Department reported it had issued only 33,370 of those H-2B visas during the busy summer months of 2022 and that this had fallen by 51 percent to 16,170, a 51 percent decline, in 2023.

One reason might be that Biden’s DHS has flooded the country with nearly 60,000 Mexicans through the CBP One app, all of them with easy-to-renew work permits.

The CBP One land port admissions, North said, “would help employers at the bottom end of the labor market.”

All of this is, of course, merely speculative. But that’s all the American people can expect when their government does policy in secret, forced only through litigation to reveal, bit by bit, what it is doing.